Will low gas prices hurt mass transit?

There might be drawbacks to the U.S. energy boom

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America, to hear CNN tell it, "is falling in love with public transit." But are we truly committed, or just flirting?

That's the question on the minds of transit advocates nationwide as we consider the landscape in 2015. As it happens, this year will see the confluence of several important transportation trends, each with implications for mass-transit ridership. The most discussed of these trends, of course, is the ongoing decline in the price of gasoline.

A bellwether year

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With $2 gas now the norm in many parts of the country, and the Energy Information Administration expecting prices to stay below $3 until at least 2017, this year is set to be a bellwether for public transportation.

That's because the $3-per-gallon mark is a special threshold. When the price of fuel drops below that, the relationship between gas prices and transit ridership diminishes considerably, according to a new study from the Mineta Transportation Institute. In other words, we have essentially reached the limit of how much low gas prices can hurt transit ridership.

Consequently, if 2015 continues to see an increase in transit usage, it would indicate that the uptick of the past 10 years is not the result of commuters wanting to cut the amount they spend on gas, but rather a more permanent cultural change in transportation habits.

Mass-transit ridership increased nearly 9 percent from 2005 to 2013, according to the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), while the level of Vehicle Miles Traveled — the best measure of automobile usage — has remained stagnant since 2007.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If this trend flatlines, or even shows a decrease, however, it would indicate that the price at the pump might have been playing a greater role in Americans' transportation decisions.

Uneven growth

Equally important in 2015, however, will be where transit usage grows.

With expanded train and bus lines opening across the country, it's easy to presume that the increase in ridership has been an across-the-board phenomenon. The media's reliance on the national APTA figures has only fed into this misleading perception.

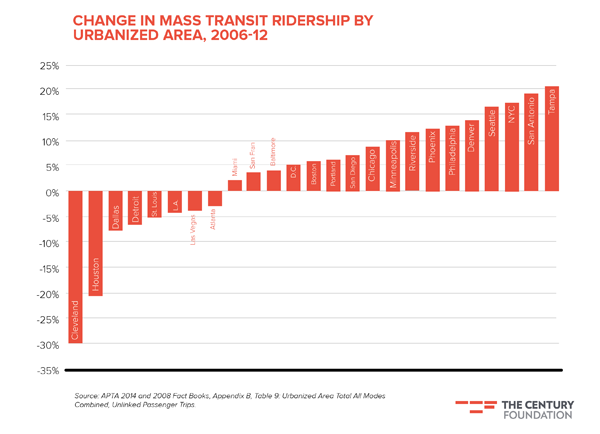

But consider this: Americans took 268 million more mass-transit rides in 2012 than in 2006. At the same time, the New York City subway saw an increase of 303 million rides.

That's not a typo — the increase in New York's subway ridership was actually larger than the net growth nationwide, as the latter statistic included decreases elsewhere in the country.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"106029","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"416","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"600"}}]]

In fact, a look at recent APTA data shows that the rising transit tide has hardly lifted all boats. Among the 25 largest urban areas in the United States, eight saw a decline in transit usage during the same 2006–2012 span. In three more cities, ridership grew by less than 5 percent.

To an extent, these city-to-city differences are why it is important to look at 2015 ridership data not at the national level, but at the local level.

The key indicators for mass transit will come from those booming urban areas in the south and west of the country — cities in which people own cars, but where effective land use and transit planning have the potential to reduce the need for them.

It's in those cities, where low gas prices have the potential to do the most damage to nascent transit projects, that the war for the future of public transportation is being waged. And if the recent past is any precedent, they exhibit a troubling lack of consistency when it comes to the growth of mass transit.

Denver, Phoenix, San Antonio, and Tampa, for example, all experienced healthy increases in transit usage from 2006 to 2012. The Dallas and Houston areas, on the other hand, posted ridership declines of 8 percent and 21 percent, respectively, even as they welcomed millions of new residents and opened dozens of miles of new rail lines. Atlanta and Las Vegas also saw drops in ridership, despite similarly impressive population growth.

States must get on board

In 2015, transit advocates must make it a priority to address these inter-urban disparities.

From a national perspective, the problem is not so much that Houston's transit usage is declining — it's that Houston and San Antonio are witnessing such different trends even as they grow in such similar ways.

That's why any effort to get cities that are lagging on transit usage on board with national trends must start with action at the state level.

As it stands, many fast-growing Sun Belt cities happen to be in states that provide virtually no financial support for public transportation, thanks to legal restrictions and traditionally transit-skeptical state legislatures.

In both Atlanta and Houston, for example, the transit authorities rely almost entirely on local sales taxes, which are socially regressive and dry up during economic downturns. Even then, they're legally required to divert some of that revenue away from transit operations.

The overall picture isn't much better. Of the 15 fastest-growing U.S. municipalities with more than 50,000 people, 14 are located in states that dedicate less than 2 percent of their gas tax revenue to transit, according to data from the Census Bureau and the Tax Policy Center.

In contrast, the venerable transit systems of the Northeast often derive a significant part of their operational funding from state coffers, or are simply owned by the states themselves.

This transit-oriented set-up is no guarantee of solvency (as any New Yorker would be quick to remind you), but it does help to dispel the foolish notion that the quality of a state's urban transportation has no impact on its fortunes more broadly.

From Georgia to Texas and Nevada to North Carolina, this is the myth that transit advocates must dispel in 2015. Otherwise, we risk becoming a country of haves and have nots when it comes to urban transit, even between cities in the same state.

The train is in the station; will states get on board?

Jacob Anbinder is a policy associate at the Century Foundation, the New York-based think tank. He writes about transportation, infrastructure, and urban affairs.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy