Between the bookstore and the gun: Life in a rattled Paris

Chapter 3 of my Paris Project

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In Paris I have rented a simple, elegantly decorated little studio in the 13th arrondissement, a boulevard or two over from the famous Latin Quarter. My room is on the ground floor of an ancient building, a convent built sometime in the 17th century, which has, at some point in the intervening centuries, been renovated into apartments. The door of my room opens onto a shared cobblestone courtyard, a quiet hideaway in the heart of a bustling city, where I can spend warm afternoons reading in the sun.

My home here is a short block away from the neighborhood square, named after the Leftist journalist and resistance fighter Claude Bourdet. Around this square, there is a small bookshop called the Bookstore of Rare Birds (Librairie des Oiseaux rares), as well as a bakery, a green grocer, a high school, a restaurant, and a café. If I walk down one of the streets that sprouts from the square, I arrive at the entrance of a charming and large neighborhood park complete with tall bowing trees, manicured gardens, a playground, communal exercise machines, and assorted nooks and crannies I haven't discovered yet.

If I instead walk down a different street that shoots out from the square, I run headlong into military and police guards carrying long automatic weapons. There are often two paramilitary guards wearing olive green camo uniforms and black berets. As parents and children walk by, the guards pace in front of the entrance to a Jewish high school across from a kosher grocery store. The guards carry black machine guns.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If I walk down another street, in the opposite direction from the high school, I arrive at the offices of Le Monde newspaper, the main entrance of which has been shuttered at least since the January attack on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. There is a metal gate pulled down in front of this entrance, with the ubiquitous Je Suis Charlie sign slung across the front. The only working entrance to the building seems to be the one on a side street with a police van idling in front. Inside the van, there are usually two police officers who are generally preoccupied with their phones. Pacing in front of this entrance is an armed police officer or two wearing bulletproof vests and brandishing automatic rifles.

The effect is unsettling. The guards and the guns are supposed to bring some comfort and a sense of safety to the students, journalists, and neighbors, while warning off terrorists. But the guards make me increasingly uncomfortable. I think this may be because many people in Paris don't automatically accept that I am an American just because I say I am. They look at me and immediately notice that I don't look like a typical white American and I am clearly not a black American, so, as often happens to me back home, they ask where I am from.

Washington, D.C., I say.

But your family isn't from there, they reply. This is a statement, not a question. They press on, not at all unfriendly. Where are you from?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I tell them that my family is from Iran and then they smile as if to say, "I knew it!"

In America, whether I am Iranian or American or Iranian-American is left up to me. I may not have always been seen as white, but I have always been accepted as American. How I chose to identify myself was left up to me. My identity thus enjoyed a certain amount of fluidity. This is unfamiliar in Europe.

I am, of course, not the first American writer to faceplant onto the question of identity while living in Paris. "It is a complex fate to be an American," writes James Baldwin, quoting Henry James, in the 1959 essay, "The Discovery of What it Means to be American." "The principle discovery an American writer makes in Europe," Baldwin writes, "is just how complex this fate is."

Indeed, much of Baldwin's work from this period reveals his preoccupation with the America he left behind. In his novel, Giovanni's Room (1956), the main character, David, is a former G.I. who finds himself in Paris struggling with his homosexuality, even as he falls passionately in love with the Italian barman, Giovanni.

Throughout the novel, David is also constantly picking at his Americanness.

When Giovanni wanted me to know that he was displeased with me, he said I was a “vrai américain”; conversely, when delighted, he said that I was not an American at all; and on both occasions he was striking, deep in me, a nerve which did not throb in him. And I resented this: resented being called an American (and resented resenting it) because it seemed to make me nothing more than that, whatever that was; and I resented being called not an American because it seemed to make me nothing. [Giovanni's Room]

David, like so many American expats before and after him, is in Paris to avail himself of the social freedom afforded to you when an entire city doesn't care a wit who you think you are or what you do. He goes to France to escape the limitations of being different in America.

As a young gay black man, Baldwin himself escaped America to outrun the implications of his own otherness. In 1948, as a 24-year-old kid with $40 in his pocket, he boarded a boat to France to leave America's “colour problem” behind him. A decade later, he wrote of his migration to Paris, in “The Discovery of What it Means to Be American" (1959) that he "wanted to find out in what way the specialness of my experience could be made to connect me with other people instead of dividing me from them.” Eventually, Baldwin came to terms with his identity as an American, complex as it was, and he was able to go back to the United States on his own terms.

I am here in Paris, because, like Baldwin and countless others, I also felt a sort of otherness back home in my small corner of America. Mine wasn't difference borne of race, class, or even religion. Back home, I felt different because I wanted different things and I wanted them differently. At another time, I might have come to Paris to be ignored by Parisians and enveloped by the American expatriate community. Eventually, I'd find my literary footing and, clutching my book, I'd thank the city on my way out the door — and perhaps this may happen still.

But the Paris I am living in right now, the one with a bookstore at the start of a block and an automatic rifle brandished at the other end, isn't just a foil for my personal, creative journey. Something is happening in this city right now. She's troubled and uncomfortable, and in the midst of a sea change — and she's all the more fascinating for it.

Read Neda Semnani's entire Paris project here:

* The quiet thrill of writing as a foreigner in Paris

* How to not write about love in Paris

* Between the bookstore and the gun: Life in a rattled Paris

* Dark days in the city of light

* The kick of rejection

* Adieu, Paris

Neda Semnani is a freelance writer at work on her first book. She is the former Heard on the Hill columnist and the arts and culture reporter for CQ Roll Call. Her work has also appeared in the Washington City Paper, BuzzFeed, CityStream, and more.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

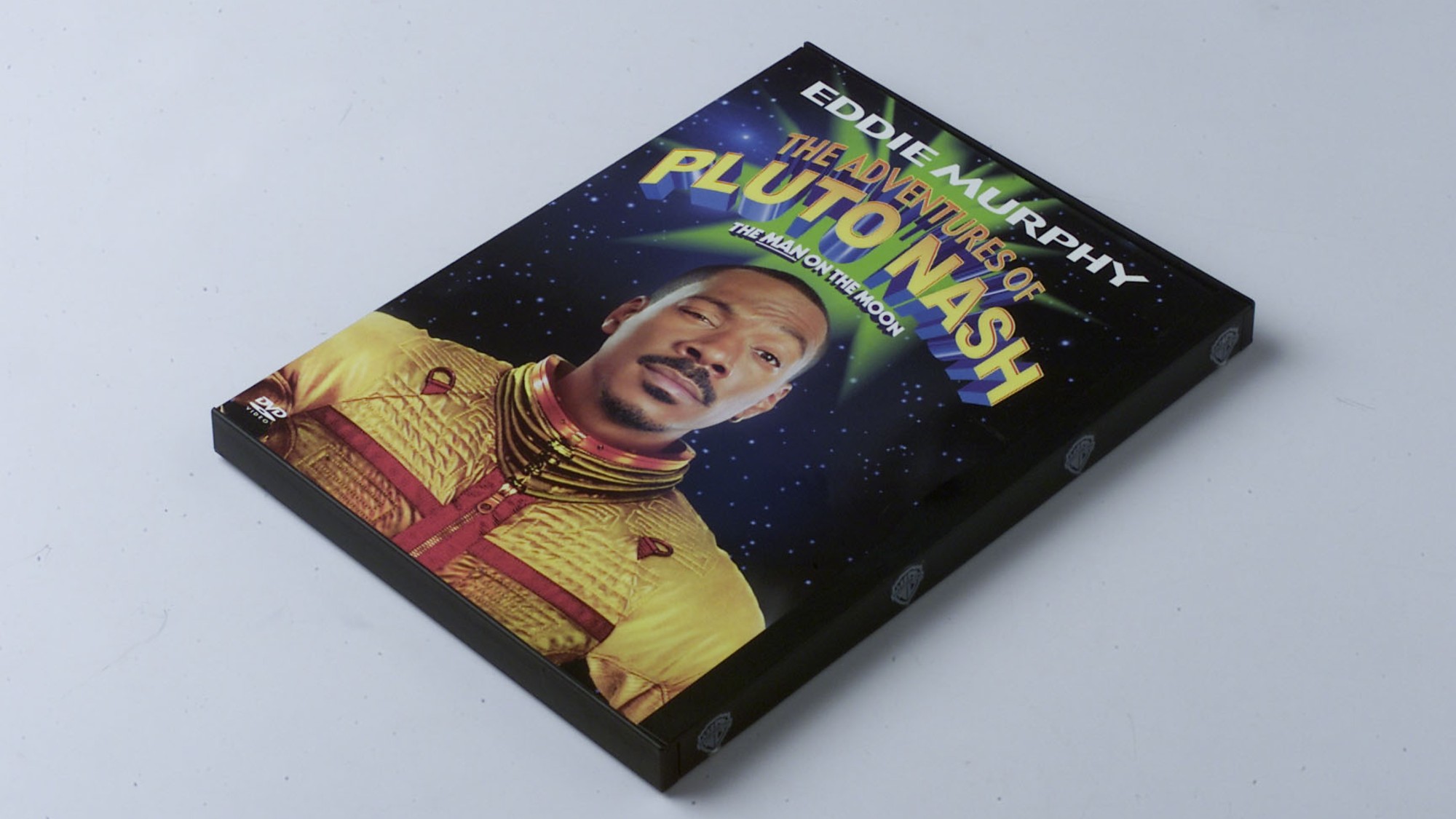

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers