Boys are sinking. Let's throw them a doll.

Our cultural obsession with gender is hurting everyone, but boys more than girls

Feminism has been good for girls, and that's something to celebrate. We take it for granted now that a girl can grow up to be just about anything her abilities and drive allow, including corporate titan, combat troop, or even president of the United States. In fact, in some circles, opting to stay home and raise children is now a countercultural choice, much as wearing pants and going to the office was 70 years ago.

Boys are doing fine, for the most part. But they're falling behind, at least in school, according a whole body of research and most recently a major report on 15-year-old students and gender by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a club of wealthier nations. In particular, more boys are failing spectacularly than girls are.

This is a survey of 64 countries, not just the U.S., but the U.S. is close to the OECD average in most measures. And the OECD's explanation for the gender gap should look familiar to anyone who went to K-12 in the U.S., or ever sat through an '80s-vintage John Hughes movie. By age 15, the OECD researchers write in "The ABC of Gender Equality in Education," you can clearly see "gender differences in attitudes toward school and learning."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

These seem to be strongly related to how girls and boys have absorbed society's notions of "masculine" and "feminine" behavior and pursuits as they were growing up. For example, several research studies suggest that, for many boys, it is not acceptable to be seen to be interested in school work. Boys adopt a concept of masculinity that includes a disregard for authority, academic work, and formal achievement. For these boys, academic achievement is not "cool." Although an individual boy may understand how important it is to study and achieve at school, he will choose to do neither for fear of being excluded from the society of his male classmates. Indeed, some have suggested that boys' motivation at school dissipates from the age of 8 onwards, and that by the age of 10 or 11, 40 percent of boys belong to one of three groups: the "disaffected", the "disappointed" and the "disappeared".... Meanwhile, studies show that girls seem to "allow" their female peers to work hard at school, as long as they are also perceived as "cool" outside of school. [OECD, p. 53]

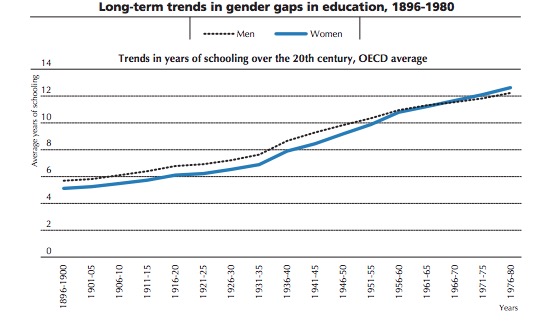

This disruptive behavior by some boys seems to affect all of them. When teachers don't know the gender of the students whose tests they are grading, the OECD found, the sizable female-favoring gender gap in reading narrows by a third. Now, the report isn't all bad news for boys — both genders are doing better than a generation earlier:

(OECD)

Still, boys are falling behind. And there are a handful of ways to address the causes identified in the OECD report. Parents could, as the researchers suggest, make their sons read more, finish their homework, and pare down their online-gaming time. Schools could adjust their curricula to better meet the needs of boys, bringing back longer recess periods and regular physical education, for example.

But I'm going to focus on the pie-in-the-sky option of changing society.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I should start by acknowledging that people are really tied to the idea of gender, whether they think they are or not. So are companies that make and market toys, clothes, and entertainment. And with some notable, admirable exceptions — growing acceptance of gays and lesbians, for example — Americans aren't less fixated on cleaving boyhood from girlhood than they were 40 years ago; in some ways we're more obsessed.

I'll use Legos as an example. In 1974, Legos included a letter in some boxes of little plastic brick toys noting that "the urge to create is equally strong in all children. Boys and girls." The insert, unearthed last fall on social media (and yes, it's real), continued:

A lot of boys like dolls houses. They're more human than spaceships. A lot of girls prefer spaceships. They're more exciting than dolls houses. [via Redditor Fryd_]

Today, Legos is selling pink boxes of Legos "Friends" for girls alongside blue boxes of (increasingly co-branded) Legos for boys — as my colleague Elissa Strauss noted recently. Boys play construction and ninjas and pirates and superheroes; girls build relationships. Strauss makes a strong case for why "girl" play is good for boys' development — but it's largely an aspirational case at this point. Nobody would think twice if a girl still decided she wanted to play with Lego spaceships — they would probably, and rightly, applaud. But imagine the looks if a boy wanted to buy some Lego Disney Princesses.

So what? Let's return to the OECD report. "Whether because of socialization or innate differences, boys are more likely than girls, on average, to be disruptive, test boundaries, and be physically active — in other words, to have less self-regulation," the study's authors write, citing previous research. "As boys and girls mature, gender differences grow even wider.... As teenagers, boys tend to be less self-disciplined than girls: They are less likely than girls to be able to delay gratification, plan ahead, set goals, and persist in the face of frustrations and setbacks."

Those, by and large, aren't "innate differences" — they're skills that most people can master, if given the right tools. (Psychologist Walter Mischel, famous for his "marshmallow test," published a book last year on how children and adults can learn self-control, for example.)

For some reason, girls seem to be mastering those crucial skills better than boys. The easiest way to remedy that might be to stop ridiculing and stigmatizing boys for engaging in "girl" activities. There are physical and hormonal differences between boys and girls, but anyone with children can tell you that each one is different from birth. We don't need to neuter or androgenize boys, just give them the same freedom of choice won for girls.

If more boys are allowed to grow into three-dimensional humans with the emotional and behavioral tools to navigate the world, I suspect we'd see their scholastic success rates rise. And more importantly, boys with better self-control and self-discipline grow up to be more productive and successful men. That's something we all should want — and something to remember when the children in your life wander to the "wrong" part of the toy aisle or the Netflix queue.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics