Libya's collapse

Liberated with Western help from Gadhafi's rule in 2011, Libya is now a largely forgotten, lawless land

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What has gone wrong?

Very little has gone right for Libya since Oct. 20, 2011, when longtime dictator Col. Moammar Gadhafi was dragged from a drainage pipe outside the city of Sirte, beaten with shoes and sticks, and shot in the head by militiamen. A NATO-led coalition had helped the rebels topple Gadhafi's much-hated regime with a punishing bombing campaign, in the hope that his fall would precipitate a new era of democracy and prosperity in the oil-rich North African nation. After Gadhafi's death, NATO leaders called their involvement "a model intervention," and President Obama declared, "Without putting a single U.S. service member on the ground, we achieved our objectives." But four years later, Libya is economically and politically broken, and may end up splitting in two. It has two governments and two parliaments; extremist Islamist militias are causing mayhem; and about 3,000 people have been killed in fighting since last summer. Libya's lawlessness and unguarded coasts have made it the main conduit for illegal immigration into Europe, leading to tragedies such as this week's boat capsizing that cost 900 people their lives.

Is the West doing anything about Libya?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Not lately. Libya comes far behind Ukraine, Syria, and Islamic terrorism on the world's list of emergencies, and the West has been reluctant to intervene since Islamists burned down the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in 2012, killing U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. But leaving Libya to its own devices was, in a sense, always part of the plan. The original "light footprint" NATO mission, led by the U.S., the U.K., and France, was supposed to put Libyans in charge of rebuilding their country. "We're under no illusions," Obama said in 2011. "Libya will travel a long and winding road to full democracy."

How did things get so bad?

One reason Gadhafi was able to hold power so long was his skill, and brutality, in dealing with Libya's numerous clans and tribal factions. Now these militias — heavily armed and with their own territorial and religious agendas — have taken over and forced the leaders of Libya's fragile official government to flee the capital, Tripoli. Thousands of militiamen have been added to the state payroll, giving them authority across the country. Libya has also become a proxy for a much wider conflict: Its Islamist groups are backed by Qatar and Turkey, while its more secular forces get weapons and funding from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the U.A.E.

Who, exactly, is fighting whom?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Two main factions are slugging it out. In the west, Libya Dawn, a coalition of Islamist groups and former rebels against Gadhafi, controls Tripoli and the main airport. The east is more or less under the control of Dignity, an alliance between Libya's House of Representatives — recognized abroad as the legitimate parliament, and currently sitting in the eastern city of Tobruk — and Gen. Khalifa Haftar, a former Gadhafi-era military commander who has vowed to "purify" the country of terrorists and Islamists'. Neither side is stable. Local militias join forces one month and turn against one another the next. In the power vacuum, some extremists are swearing allegiance to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria; ISIS fighters beheaded 21 Egyptian Christians in February and shot an unknown number of Ethiopian Christians this week.

Which side is going to win?

Neither Libya Dawn nor Dignity seems capable of taking control of the country by force. What may prove decisive is not military strength, but money. Libya has Africa's largest oil reserves, but the oil is ceasing to flow. Recent raids by ISIS fighters have closed 11 oil fields; exports are running at 200,000 barrels a day, a fraction of capacity. Mashala Zwai, one of the country's two oil ministers, says Libya will run out of money in 18 months if normal supplies aren't soon resumed. "By next year," he says, "the state won't be able to pay Libyans' salaries."

What impact will all this have?

The effects of the conflict are already being felt across the region. Arms from Libya are turning up in Syria and in sub-Saharan Africa, and the steady stream of tens of thousands of illegal immigrants through Libyan ports has Europe in an uproar. In the longer term, the chaos will likely deter the U.N. and NATO from embarking on similar interventions to protect civilian populations or topple dictators. Obama said last year the West had "underestimated" how much assistance would be needed once Gadhafi was forced out. "If you're gonna do this," Obama said, "there has to be a much more aggressive effort to rebuild societies." In recent months, a constitutional assembly led by economics professor Ali Tarhouni has tried to write a new constitution that would unite the country by giving each faction a share of power — a plan backed by the U.N. But militia leaders seem more interested in settling their differences on the battlefield. "The only moderates in this country are the ones who are forced to be," says Tarhouni. "The military situation has to mature more before the conditions are ripe for a dialogue."

National savior, or another Gadhafi?

Of all the politicians and militia leaders now battling for supremacy in Libya, Gen. Khalifa Haftar is the figure most likely to decisively influence the country's future. A former army cadet, Haftar joined Gadhafi's coup to seize power in Libya in 1969. He led a war against Chad in 1987, but was disavowed by the Gadhafi regime after being captured by enemy troops. For 20 years, Haftar lived in the U.S., in northern Virginia, and from there led the National Front for the Salvation of Libya, a CIA-backed group that plotted the overthrow of Gadhafi. When his country fell into chaos after Gadhafi's death in 2011, he headed home to lead the Dignity alliance. His sole ambition, he tells The New Yorker, is serving "the people's needs." When asked if that service could one day include running for president, Haftar smiled and replied, "I would have no problem with that."

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

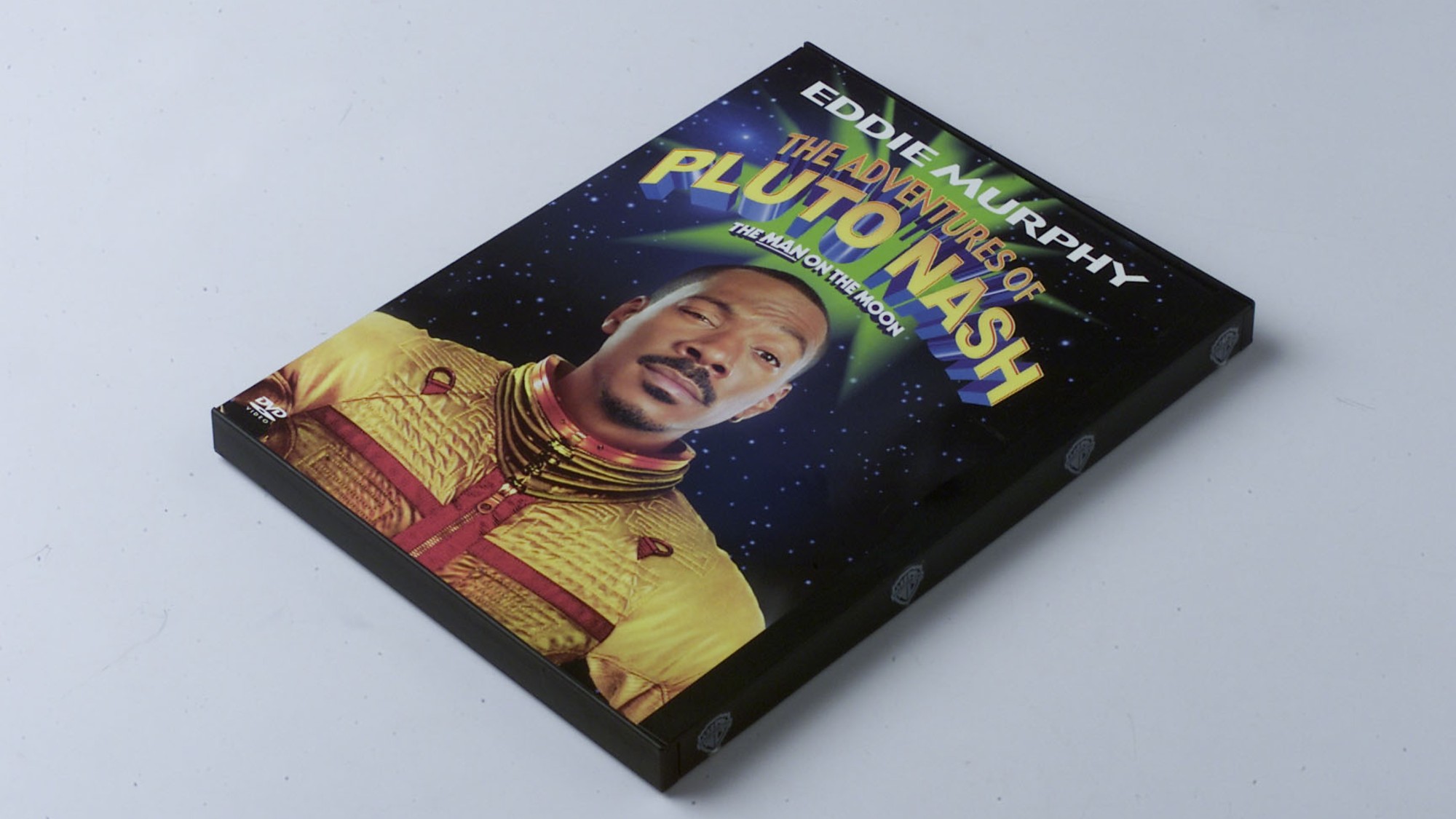

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

19 Kids and Counting's Josh Duggar hit with child pornography charges

19 Kids and Counting's Josh Duggar hit with child pornography chargesSpeed Read

-

Matt Gaetz was the main opponent of Florida's nonconsensual 'revenge porn' law, GOP lawmaker says

Matt Gaetz was the main opponent of Florida's nonconsensual 'revenge porn' law, GOP lawmaker saysSpeed Read

-

Georgia police arrest Black lawmaker for knocking as Gov. Brian Kemp signed new voting restrictions

Georgia police arrest Black lawmaker for knocking as Gov. Brian Kemp signed new voting restrictionsSpeed Read

-

Myanmar junta reportedly kills 38 protesters, declares martial law in part of Yangon

Myanmar junta reportedly kills 38 protesters, declares martial law in part of YangonSpeed Read

-

Raskin asks FBI for answers on how it's targeting white supremacists in law enforcement

Raskin asks FBI for answers on how it's targeting white supremacists in law enforcementSpeed Read

-

Ahmaud Arbery's mother files civil rights lawsuit 1 year after his death

Ahmaud Arbery's mother files civil rights lawsuit 1 year after his deathSpeed Read

-

Lawyer for man charged in Capitol riot says he worked for the FBI, had top-secret security clearance

Lawyer for man charged in Capitol riot says he worked for the FBI, had top-secret security clearanceSpeed Read

-

Trump's impeachment lawyer specializes in medical malpractice and 'people falsely accused in Me Too cases'

Trump's impeachment lawyer specializes in medical malpractice and 'people falsely accused in Me Too cases'Speed Read