What America can learn from Europe's confused quest for shared values

Rights and values are not the same thing...

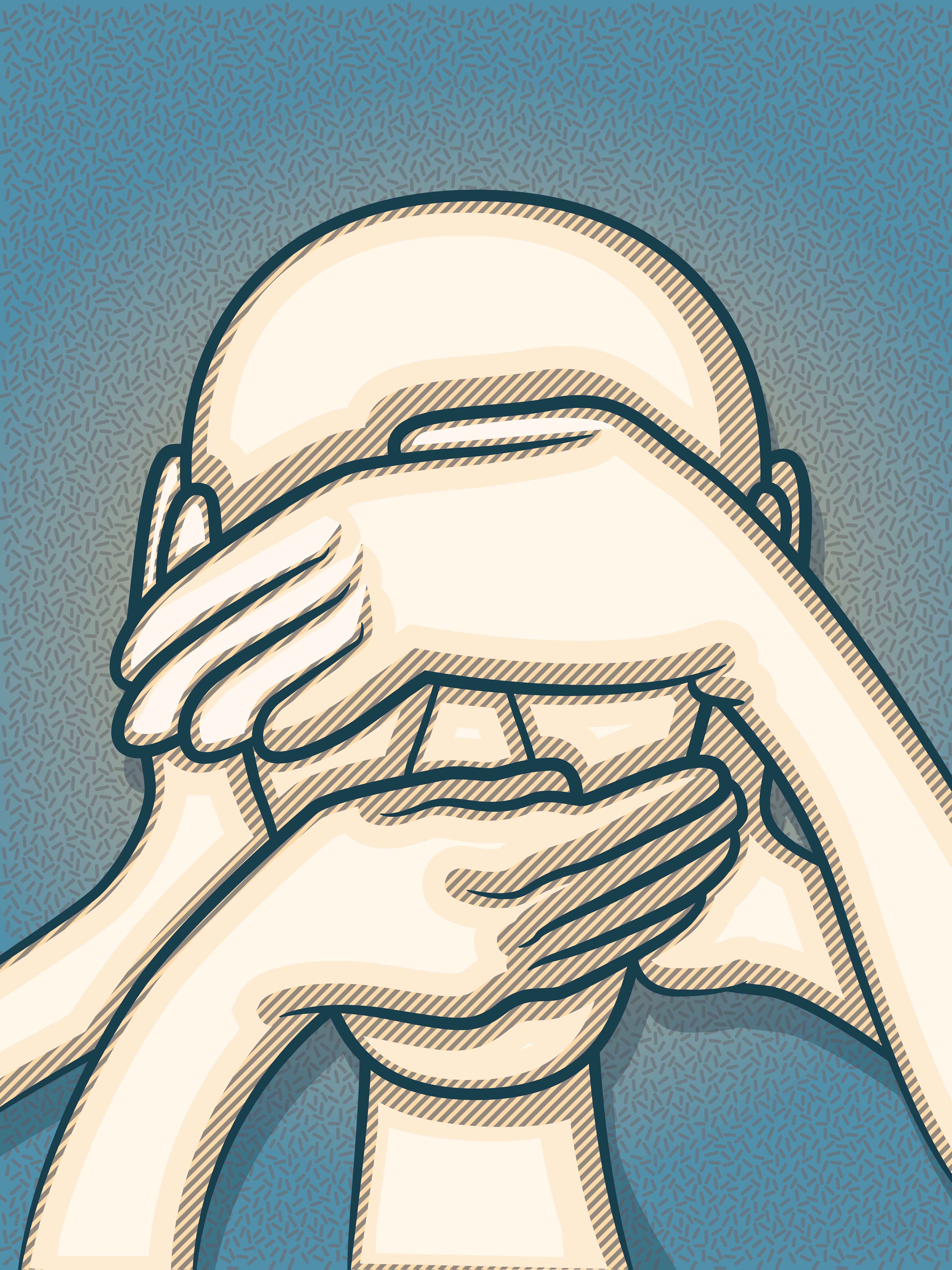

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks, the French government has moved to establish a draconian surveillance law that would chill speech even for members of the press. "Reporters Without Borders warns the bill would seriously compromise journalists' ability to protect sources, as well as their ability to quote or relay via visual media the statements of any group or individual deemed terrorist by the government," according to The New York Times. This is a direct curtailment of freedom in the name of security.

Something that at first seems similar is happening in Britain. Flush with victory, the Conservative party is out to reform speech and expression laws in accordance with its "one nation" view of governance. Speaking at the British National Security Council, Prime Minister David Cameron recently unveiled a scheme set to send shock waves through liberal Britain. Warning that a posture of official value-neutrality has "helped foster a narrative of extremism and grievance," he promised his government "will conclusively turn the page on this failed approach. As the party of one nation, we will govern as one nation and bring our country together. That means actively promoting certain values."

In many ways, this is also a direct curtailment of freedom in the name of security. Promoting certain values also means limiting other values, and putting caps on certain kinds of speech and expression in the name of increased security, not just against terrorism, but cultural illiberalism. Emma Norton, a legal officer at the civil liberties group Liberty, captured idealists' dismay at Cameron's fight-fire-with-fire approach. "Driving those who despise diversity underground does nothing to challenge their beliefs. You don't protect democracy by undermining the freedoms that sustain it," she told The New York Times.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But there's more to it than that. The following are among the British values Cameron says British law must promote: "Freedom of speech. Freedom of worship. Democracy. The rule of law. Equal rights regardless of race, gender, or sexuality." It all sounds nice at first. But some of these things are rights ("freedom of speech") and some are not ("the rule of law"). Some ("Democracy") are better described as an amalgam of institutions, traditions, and ideals.

By lumping them all together in such an intuitively pleasing way, Cameron reveals just how abstract and imprecise our sense of Western liberalism has become. Secretly, one gathers, he, like so many of us, believes that the liberal West requires all these things to be embraced as a package deal. It's not merely about ensuring fundamental rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It's about the romantic vagaries of feel-good phraseology.

But here's the thing. The phrasing feels good because it gratifies a desire that rights alone can't satisfy: our longing for collective pride. We want to celebrate more than what we're free to do and free from having to do. We want to celebrate who we are. Alas, identity politics at their most powerful and dangerous arise when government sees "promoting" identity as its primary purpose.

Muddling the distinction between rights and values creates a comforting vagueness in the service of what ought to be a discomfiting goal — top-down identity politics. In a free society, we can place great value on something without enshrining it as a right. After all, we don't have a right to everything we like. But "values" talk stakes out a set of things so important that they're off the charts of value. They’re not just what we like, they're who we are.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Again, at first blush, that sounds harmless enough. A country without an identity would be a bizarre, unstable place to live. But a country where values are enforced can be even worse. We're liable to find ourselves without the freedom to decide how much we like who we're given to be.

That's why the U.S. is so fortunate to have a culture powerful enough to digest or transcend the diverse subcultures our immigrants have brought our way. Although the political promise of America has inspired many a newcomer fleeing an oppressive land, it's the day in, day out reality of American culture that makes us into "one nation." And it's our national insulation from radically indigestible, illiberal immigrants that has allowed us the space to grow that kind of culture.

That's a New World luxury that Britain and the rest of the West have gone without. In a free society, you can't just hound people off your soil, no matter how alien they are. Yet European nations, afraid of their own cultural shadow, can't find a way to weave their illiberal immigrants into the fabric of their shared identity.

That makes identity a political problem in a way Americans just don't have to face. But the resulting conflict, which pits values' unlimited claims against ever-more-abstract visions of rights, resonates all too clearly with the bottom-up politics of identity that's increasingly burdening American culture. On either side of the Atlantic, the question of who we are must give way to the question of how we can choose to be.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history