The literary crimes of Go Set a Watchman

Are we really to believe that the Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird is darker than he seems?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

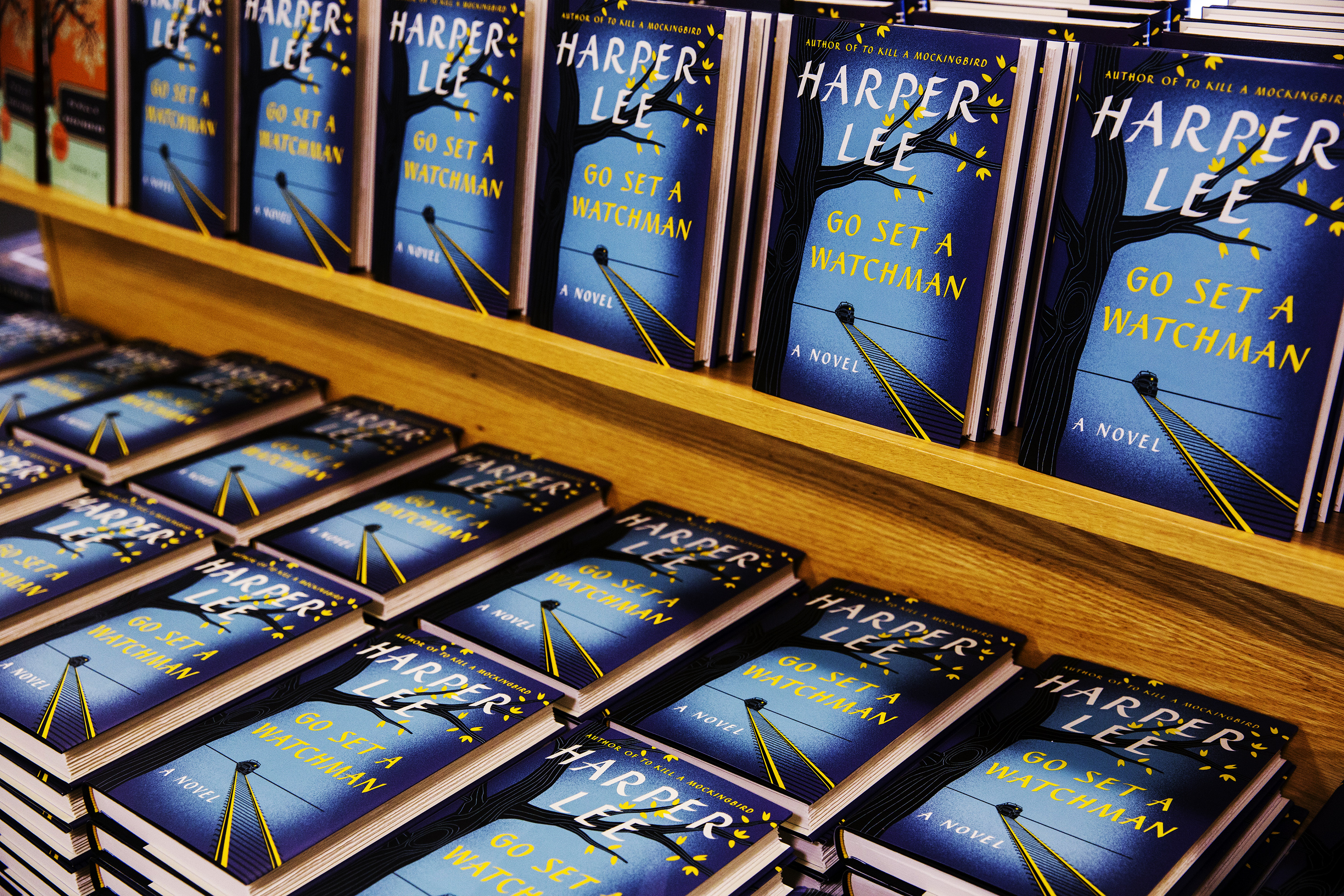

The publication this week of Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman, the long-lost cousin of the classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird, has only inflamed the controversy that has surrounded the book from the day its existence was revealed to the public. The revelation that the beloved character Atticus Finch is depicted as a racist in Watchman, which started its life as an original draft of Mockingbird rejected by Lee's publisher, has only deepened suspicions that she has fallen victim to a predatory scheme concocted by her lawyer and abetted by a publishing company salivating over the prospect of a guaranteed blockbuster. Judging from the response so far, the book is, at best, an interesting literary artifact, showing how Lee transformed her disillusionment with white America into a powerful morality tale about racial justice and equality; at worst, it may be the most spectacular example of a revered author unwittingly destroying her own legacy.

If Watchman had been sold as an object of literary history, much of the ongoing controversy would have been avoided. But the discarded pages that line a novelist's wastepaper basket aren't exactly bestselling material, even if the novelist is Harper Lee. The book's publisher in the United States, HarperCollins, has insisted instead that Watchman is "in many ways a sequel" to Mockingbird, and that it is a "brilliant book" and a "masterpiece that will be revered for generations to come." (Full disclosure: Many years ago, HarperCollins gave me my first full-time job out of college.) The book's jacket copy boasts that it is "a magnificent novel in its own right," even as it "casts a fascinating new light on Harper Lee's enduring classic." So here we have two arguments for the book's publication that might redeem what otherwise looks like a lurid story of greed, cynicism, and exploitation: that Watchman is a masterpiece "in its own right" and that it introduces new complexity to a familiar story.

The problem with the former argument is that Watchman, despite coming first, would not exist in published form without Mockingbird. Whatever its merits, which I will leave to others to parse, there is little reason to read Watchman unless you already know the story of Mockingbird and its characters. That Watchman is set at a later date, featuring much older versions of Scout and Atticus, only strengthens its dependence on Mockingbird. In the most optimistic scenario, Watchman could one day grow to such stature that it becomes Mockingbird's spiritual twin (or perhaps its triplet). But it occupies a strange space that is neither sequel nor standalone book; it is Mockingbird's alternative universe, where even the main facts of the narrative, such as Tom Robinson's conviction on charges of rape, are changed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That leads us to the latter argument, which is far more intriguing and has been tentatively embraced by certain critics and academics. As the novelist and critic Thomas Mallon told The New York Times: "If Atticus Finch is not quite the plaster saint that he is in To Kill a Mockingbird, there could be something rich and fascinating about that… The moral certainties in To Kill a Mockingbird are apparent from the first page, and in that sense, I don't think it's a great novel that deals with the tormenting questions of race in America, but maybe this new one is, if it's more nuanced."

Charles J. Shields, who wrote Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, told the Times: "It turns out that Atticus is no saint, as none of us are, but a man with prejudices."

As someone who is not one of Mockingbird's ardent admirers, these criticisms certainly have some appeal. But the implication that Mockingbird is a simple book helmed by a simple character beloved by white simpletons in search of an easy resolution to America's legacy of racism (or worse, absolution for the crimes of Jim Crow) mistakes how the novel — or at least a certain kind of novel — works. And in this respect, the greatest crime of Watchman's publication is truly literary in nature, representing a deep confusion about the way stories are told.

There is an apocryphal anecdote about a meeting between Charles Dickens and Fyodor Dostoevsky that will help explain what I mean. It features Dostoevsky writing the following of Dickens in a letter to a friend: "All the good simple people in his novels, Little Nell, even the holy simpletons like Barnaby Rudge, are what he wanted to have been, and his villains were what he was (or rather, what he found in himself), his cruelty, his attacks of causeless enmity toward those who were helpless and looked to him for comfort, his shrinking from those whom he ought to love, being used up in what he wrote. There were two people in him, he told me: one who feels as he ought to feel and one who feels the opposite. From the one who feels the opposite I make my evil characters, from the one who feels as a man ought to feel I try to live my life. ‘Only two people?' I asked."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The punchline is about Dostoevsky and his clamorously peopled novels. But the anecdote also shows the way To Kill a Mockingbird borrows from a rich literary tradition in which the different characters stand for different elements of a single soul. Dickens' characters, particularly the good-natured ones, are notoriously one-dimensional, but few would say his books are simplistic. Similarly, Atticus Finch is an almost faultless hero, guilty as charged; his whole purpose is to provide an example that the reader both recognizes and can aspire to, what the critic Northrop Frye called "the hero of the high mimetic mode." Everyone is familiar with this kind of hero, whether he is Hector or King Arthur or Gandalf (or Jesus). He is not meant to be a realistic figure per se; he is but one part of a universe replete with bad people full of prejudices, selfishness, and hatred — awful traits that also exist within ourselves. The evil characters in Mockingbird are not wholly alien to us; in a famous scene, Scout literally recognizes Tom Robinson's would-be lynchers.

(That the hero in Mockingbird is white has touched off a different discussion about whether Mockingbird itself perpetuates racist ideas about white superiority and black submissiveness — but that is for another essay.)

The Atticus Finch of Watchman, in contrast, is complex and contradictory. He is a trial lawyer who once helped acquit a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman, but also a segregationist who can ask his daughter, "Do you want your children going to a school that's been dragged down to accommodate Negro children?" This is a character who is highly flawed and more realistic. He is a different heroic type, the kind who "is one of us," as Frye wrote, and "we respond to a sense of his common humanity, and demand from the poet the same canons of probability that we find in our own experience."

This is a perfectly acceptable hero, living and breathing in the kind of fictional world that many people, including myself, prefer. The problem is that Lee can't have it both ways. Mockingbird is on a different literary plane than Watchman, and the two can only meet awkwardly, which is precisely what HarperCollins has demonstrated by grafting Watchman onto Mockingbird. They cannot work together in any meaningful sense; one cannot cast a new light on the other, except in the way an apple sheds light on an orange by being, well, different.

This is why, on a gut level, so many readers rejected the great revelation of Watchman. Are we really to believe that the Atticus of Mockingbird is far more complicated than he appears? This idea is a mockery not only of common sense, but also of the internal logic of the book.

If Harper Lee really wanted to provide Atticus with another, darker dimension, and thought Mockingbird gave too simplistic a treatment of the fight for racial justice, then she would have been better off writing a sequel (or a prequel or a spin-off) that grew organically out of her classic novel. Instead, her fans are left with a first draft by a first-time novelist that is trying desperately to be something that it's not.

Ryu Spaeth is deputy editor at TheWeek.com. Follow him on Twitter.