The West has a big Turkey problem

Blame the Mideast's tangled and contingent alliances

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a newly active coalition partner taking the fight to ISIS: Turkey. That might seem like good news. But really, it ought to be a dark reminder of how messed up the Middle East really is.

In the waning decades of its centuries-long run, the Ottoman Empire was derisively known as the Sick Man of Europe. And its death at the hands of the Allied powers in World War I gave birth to a nightmare. The old imperium, held together by Islam, gave way to a new patchwork of nation-states — first Turkey, and then, after decolonization, the Arab countries — where monopolies on political violence, not on religious authority, often determined who ruled. Building nation-states out of Ottoman and European imperial rubble led directly to despots and dictators. Many of these strongmen, particularly in places like Iraq and Syria, leveraged loyalty through ethnicity and tribe that didn't fit neatly with the arbitrarily drawn borders of nation-states. And time and again, regime trouble has touched off a chaotic scramble among a shifting array of warring groups — from Lebanon in the '80s to Iraq in the '00s to Syria today.

Which brings us to Turkey, whose absurd status as a NATO ally mostly aligned against American interests has attained a new level of perversity. Although the situation continues to unfold out of a multi-layered game few outsiders can truly comprehend, the gist is this: Publicly, NATO and the U.S. stand strongly with Turkey; privately, all hell is breaking loose.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Publicly, Turkey has thrown in against ISIS, motivated by some suicide bombings the would-be caliphate carried out despite Turkey's tacit support. In a plan concocted with the U.S., Turkey will help make a refugee safe zone out of a stretch along the border with Syria, seen as a critical supply corridor for ISIS.

But as always, the Mideast's tangled politics are vastly more complex than they first seem. A trove of intelligence seized by the U.S. during a raid killing Abu Sayyaf, the Islamic State's oil and gas chief, revealed that the Turks developed close, direct, and sustained contacts with top ISIS figures. Although the U.S. has no desire to see ISIS sweep the region or conquer Syria, ratcheting up the fight against ISIS with Turkish help is more about twisting the Turks away from ISIS than it is forestalling the caliphate. Nobody expects the safe-zone effort to be a smashing success. Rebel groups backed by the U.S. are among the most skeptical.

There's another twist: Publicly, the U.S. is enthusiastic that Turkey will help share the burden of fighting ISIS, which has long fallen squarely on the Kurds. More privately, Turkey is enthusiastic about using its begrudging opposition to ISIS as a pretext for more attacks on Kurdish fighters, some of whom — in a classic reprise of the Mideast's bonkers pattern of contingent alliances — are functionally indistinguishable from the guerrillas based in Turkey that both Ankara and Washington officially consider to be terrorists.

All of this is fairly damning to a White House that seems to think it's making all the right moves. Everything hinges on whether the administration can achieve what seems to be its one clear goal in the region: replacing the Assad regime with some kind of coalition that doesn't include ISIS.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But in the meantime, the following unhappy events have transpired: Turkey has become an ally nearly as problematic as Saudi Arabia or Pakistan; the Kurds have grown nervous that the U.S. can't be counted on for support; the whopping 54 American-trained Syrian rebels lost their leader to capture by al Qaeda pals the Nusra Front; and Iran has kept up its hostile rhetoric despite securing badly needed sanctions relief through the nuclear deal. Great!

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

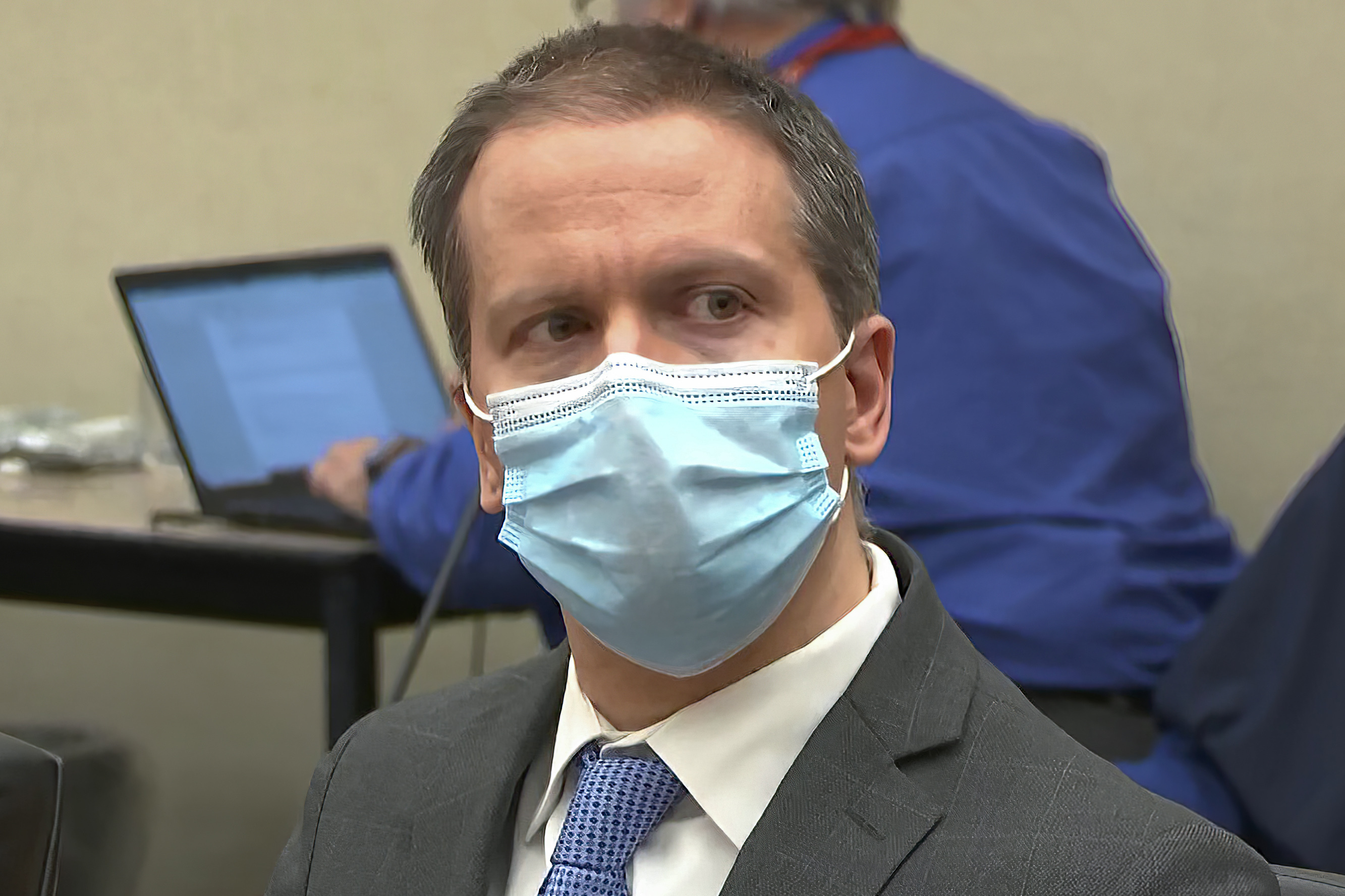

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read