One of the last hopes to defeat climate change just got debunked

Science finds that forests won't rescue the planet after all

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Forests eat a lot of carbon dioxide — roughly a quarter of humanity's total yearly output. So when it comes to the future trajectory of climate change, the behavior of forests is one of the largest potential variables. If forests grow and thrive as the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide increases (thus providing them more potential food), then climate change could be strongly mitigated.

On the other hand, if changing weather patterns fueled by global warming kill them off instead, they could release much of the carbon contained in their wood, as they die and rot. The potential range is enormous, says climatologist Dr. William Anderegg, associate professor at the University of Utah and lead author of a new paper in Science on trees and drought. By 2100, world forests could go from a net carbon sink of roughly six billion metric tons per year, to a net source of about the same size.

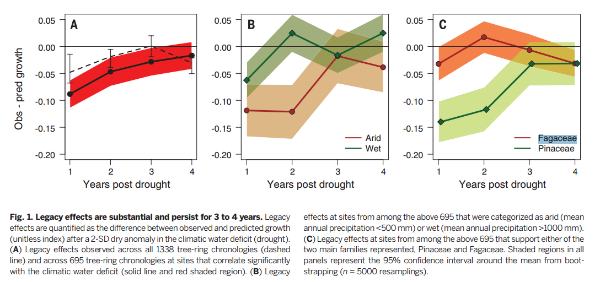

Anderegg's paper is about hysteresis in forests, a term that might be familiar from economics. Climate change will likely cause increased drought as it gets worse, and just as long spells of unemployment can have lingering effects on those who suffer it, "droughts have lasting effects on ecosystems of forests," says Anderegg. Forests grow slower during droughts, of course, but they also grow slower after the drought is over. In the first year after a drought, Anderegg and his team found trees grew an average of about 9 percent slower; in the second year about 5 percent. They estimate this effect could result in a 3 percent decline in the total carbon stored across their sample size by 2100.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The study also reveals a significant weakness with most major climate models. "Most models don't have mechanisms for drought stress," says Anderegg. Instead, they have a light-switch model, where drought has negative effects while it's happening, but they vanish instantly when the drought is over. He and his colleagues are working to incorporate their drought results into climate models. It's a tricky task, since the models are already very complicated and computationally heavy, but they are close to developing a streamlined technique that can capture most of the measured effects, he says.

This figure shows the overall average effect of drought across the sample size on the right, the difference between wet and arid forests in the middle, and the difference between Pinaceae (the pine tree family) and Fagaceae (that of beech and oaks) on the right:

However, one must be careful not to over-generalize at this point. Anderegg and his team mostly studied semi-arid forests in North America and Europe. Tropical and boreal forests — which make a far greater proportion of forests overall — were largely not studied.

The reason they didn't is simply measurement challenge. Tropical forests, in particular, are dramatically more difficult to study, because most of the trees do not create rings as they grow. (Since the tropics typically don't have regular seasons, growth is basically even and constant.) Without rings, then one is forced to rely on foliage studies from satellites or aerial photography, which are reasonably easy to do but don't contain the whole history of each tree. Or, one can go into the forest and take regular manual measurements of tree size, which is similarly missing the history, and is also enormously labor-intensive. (Not to mention the fact that many tropical regions, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, are chronically unstable with poor infrastructure.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, this study is still suggestive. The 3 percent figure given above is "almost certainly an underestimate," says Anderegg. Drought does not just weaken trees, it also kills them. Studies on recent drought in the Amazon and Borneo found significant mortality, particularly among the largest trees. More recently, scientists have found a slowing rate of carbon uptake in the Amazon.

So in context, Anderegg's paper is a reasonably strong piece of evidence pointing towards the hypothesis that forests will not be a net carbon sink. Best not to pin our hopes for climate change on future mega-forests.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

Are zoos ethical?

Are zoos ethical?The Explainer Examining the pros and cons of supporting these controversial institutions

-

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?The Explainer By spurring vaccine development, the pandemic is one crisis that hasn’t gone to waste

-

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so far

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so farThe Explainer Effectiveness, doses, variants, and methods — explained

-

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.The Explainer Wildfires are forcing people from their homes in droves. Where will they go now?

-

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisis

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisisThe Explainer On the coming epidemic of despair

-

The growing crisis in cosmology

The growing crisis in cosmologyThe Explainer Unexplained discrepancies are appearing in measurements of how rapidly the universe is expanding

-

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?The Explainer The many problems with GM's Cruise autonomous vehicle announcement

-

The threat of killer asteroids

The threat of killer asteroidsThe Explainer Everything you need to know about asteroids hitting Earth and wiping out humanity