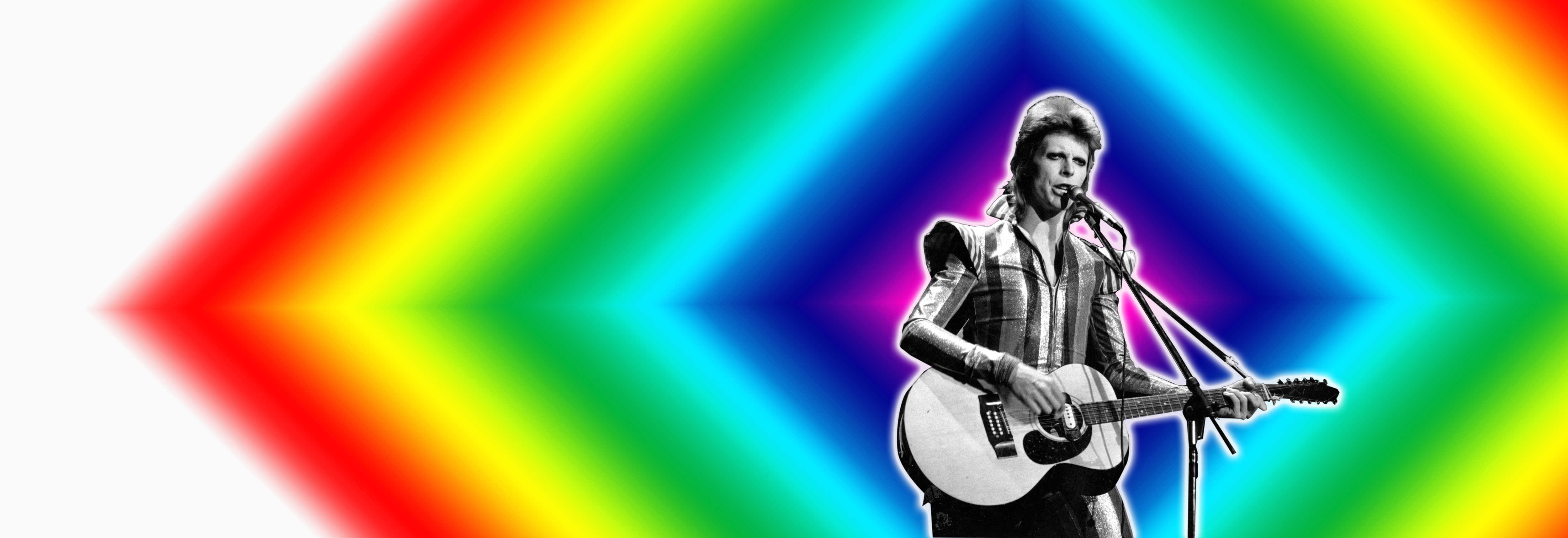

David Bowie: Portrait of the artist as a rock god

We've never seen anything quite like David Bowie — and we may never see anything quite like him again

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There was a time in the mid-1970s when the world wouldn't have believed David Bowie died just two days after the release of a new album. It must be part of the concept, we would have presumed — some new persona, character, or artistic gesture he'd devised to go along with the latest metamorphosis in his music.

But it doesn't work like that anymore.

When I heard the news of Bowie's death from cancer just two days after the release of his 25th studio album on what was also his 69th birthday, a part of me crumbled inside. For eleven years, from 1969 to 1980, Bowie was the most creative person working in pop music, and no one has surpassed him since. KISS, Madonna, Lady Gaga — each of them and so many others have followed in his footsteps, but none of them have achieved what he did: melding melody, lyrics, arrangements, singing, album-cover art, hair style, clothing, and concert performance into the seamless whole of a comprehensive artistic statement. (Even his eerie eyes — one blue, the other green, with one pupil permanently dilated from a childhood injury — seemed in on act.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Each of the 12 albums of original material he released in those years is one of those statements — the anchor for an idea, an image, a life transmuted into a work of art. Do I love everything on those records? Not even close. But they demanded, and rewarded, all-encompassing attention.

Americans like to think of rock bands (like tech companies) starting up in garages. But in 1960s Britain, some of the best bands emerged from art school. The Who's Pete Townshend, Pink Floyd's Rogers Waters, Queen's Freddie Mercury — all of them, like Bowie, studied painting, design, architecture, and other fine arts while in school. And that education left a mark on their music, which combined rock musicianship and attitude with a level of ambition and theatricality that was rare in its day and all but extinct in our own.

But Bowie went further than the others, pushing artistry beyond songwriting and even concept albums and rock operas to create something more holistic, all the while producing music that ranged widely, tested boundaries on multiple fronts, and fused pop songwriting and image-making with elements of avant-garde.

Listen to the first four of those 12 albums and be astonished at how utterly distinctive they are. The sci-fi infused Space Oddity gave us the iconic title track with its beguiling melody and chilling story of astronaut Major Tom marooned in outer space. Released the following year, The Man Who Sold the World was filled with sludgy heavy metal, while Bowie showed up incongruously on the cover reclining on a couch and wearing a dress. A year after that came Hunky Dory, jam-packed with beautiful melodies embellished with piano and strings, while vocally Bowie did his best Anthony Newley impression, swooning like a flamboyant cabaret singer out to seduce every person in the theater.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And then, finally, in 1972 there was The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, which gave the world its first fully realized Bowie persona — an androgynous spaced-out would-be glam-rock superstar fighting for fame in the shadow of impending apocalypse. (The Earth is given five years to live on the album's stunning opening track.) The record ends with Ziggy's "Rock and Roll Suicide," and yet there he was with red-rooster hair and makeup, promoting the album on stage with his back-up band The Spiders from Mars. Life and art melded as Bowie lived out the commercial ascent of the very character he'd created.

And on it went, as Bowie's voice underwent one of the most dramatic shifts in pop music history — changing, in a little more than two years, from a high, thin, wavering tone that often led him to sound like a castrato to a deep baritone croon that could reach bass notes in a pinch. Bowie credited the change to a cocaine habit (with nasal drainage apparently thickening his vocal cords).

Whatever its cause, the shift only added to the disorientation as Bowie put out a grungy rock opera (and highly theatrical concert tour) inspired by Orwell's 1984 and then followed it up, less than a year later, with his first foray into what he called "plastic soul," with arrangements filled with funk and honking saxophones. Less than a year after that, he was the blissed-out, skeletal Thin White Duke, "throwing darts in lovers' eyes" and ruminating about the "the side-effects of the cocaine" on the epic 10-minute title track of 1976's Station to Station.

Then the withdrawal to Berlin for his immensely influential trilogy with Brian Eno — Low, "Heroes," and Lodger. Has a major pop star ever put out less commercial music than these three albums? The first two are half-filled with moody, ambient instrumentals, while the bulk of the remaining songs on all three albums veer between an icy robotic vibe and art-house, angular dissonance. Yet even with these most challenging albums, Bowie managed to get played on he radio, with Low's "Sound and Vision" and the title track from "Heroes," becoming FM-radio staples.

If you doubt how difficult and artistically uncompromising Bowie could be in this period, take a look at his performance of Lodger's "Boys Keep Swinging" on Saturday Night Live in 1979. (You won't believe your eyes.)

Or listen to his jarring cover of "Alabama Song" by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. Or put on "It's No Game, No. 1," the lacerating opening cut off the album that stands as the greatest and most enduring work of his career — 1980's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). You'll hear Bowie screaming the lyrics "as if he's literally tearing out his intestines," while Michi Hirota barks a translation of the words in spoken Japanese.

Somehow, inexplicably, it works — and serves as a shockingly powerful lead-in to a record on which Bowie unflinchingly confronts his most terrifying demons, including an unsettling return to the story of Major Tom in which he reveals that all along it was a metaphor for alienation and addiction. "Ashes to ashes / Funk to funky / We know Major Tom's a junky / Strung out on heaven's high / Hitting an all-time low." If you think that music videos are inevitably cheesy and usually thoughtless promotional vehicles, watch the haunting, experimental four-minute film for "Ashes to Ashes." You'll never forget it.

After an unprecedented three-year break from recording, Bowie returned in 1983 with Let's Dance, the most accessible album of his career, and it catapulted him to an unprecedented level of superstardom. He'd occasionally make vital music again — the first Tin Machine album (1989) has some great scrappy hard-rock moments; the techno-industrial Earthling (1997) has touches of greatness, too; and Heathen (2002) was a real return to musical form — but most of the all-encompassing artistry was gone.

When rock stars die, they aren't forgotten. Their hits get played, their influence gets noted, their biggest pop-culture moments get remembered. It will be no different for David Bowie.

But Bowie was different. He was something more than a rock star, something rarer — a genuine artist whose life and music and lyrics and voice and image and even his fame itself, for a time, was his medium.

We've never seen anything quite like it, and we may never see anything quite like it again.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal