The problem with 'Uber for welfare'

No, the sharing economy isn't going to fix unemployment

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Can the gig economy remake the American welfare state?

Derek Khanna and Cesar Conda — a former congressional staffer and a former White House policy advisor, respectively — think it can. Call it "Uber for welfare." And it will finally allow government to impose work requirements, not just on traditional welfare, but across multiple government aid programs: SNAP, housing assistance, and Medicaid.

"Some opponents of workfare have argued that work requirements are untenable because the government cannot find a job for every welfare beneficiary," they wrote in Politico. Khanna and Conda consider this a bureaucratic and technological hurdle. Because jobs have traditionally been 9-to-5 affairs, and because our jobs have historically occurred in particular geographic spots (the factory floor, the restaurant, etc), linking welfare recipients up with available work is a practical difficulty. But platforms like Uber, TaskRabbit, and Instacart upend the 9-to-5 routine, and a lot of work now occurs almost entirely in digital space. So Khanna and Conda argue the gig economy "can easily and quickly put millions of people back to work, allowing almost anyone to find a job with hours that are flexible with virtual locations anywhere."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

They suggest that government offices establish "an updated directory of available gig economy jobs in the area" and provide people with computers and other tools for digital work if they don't have their own. But the key point is that there's no longer any excuse for offering government benefits without the condition that the recipient be either employed or seeking employment.

Clever as it may seem, this proposal illustrates one of the most common mistakes policymakers make when it comes to basic economic mechanics. They assume that jobs are always just "out there."

Aggregate demand — the amount of goods and services consumers have the motive and the means to buy — is the basic fuel out of which individual jobs are created. Many people tend to focus on investment as the key to growth, but investment merely creates the capacity for more activity in the economy. To turn that capacity into productive economy activity — to make sure every building is put to use, every bulldozer is running, and every person who needs a job is working — requires sufficient aggregate demand.

When we have enough aggregate demand to make use of all our capacity, we have full employment. And one of the most striking things about the last hundred years or so is how routinely we failed to achieve it. The only exceptions were those periods when the government deliberately stimulated the economy with loose monetary policy and deficit spending in a sustained fashion. Full employment happened due to the work programs of the New Deal, the massive economic mobilization and government deficit spending for World War II, and the post-war expansion of the middle class through programs like the G.I. Bill.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Khanna and Conda are quite taken with the ways the gig economy can break up, reassemble, and redefine employment: "[Welfare recipients] could deliver goods and groceries for Postmates and Instacart, assemble furniture on TaskRabbit or mow lawns and plow driveways with PLOWZ & MOWZ," the two wrote. "They could offer photo shoots, voice lessons, mural painting, tennis lessons, or painting a house on Thumbtack," and on and on into graphic design, legal work, and coding. But Khanna and Conda simply ignore the question of whether there is enough demand in the economy — enough consumers with the necessary money — to pay for all of this employment. Insisting welfare recipients work makes little sense when there literally aren't enough jobs for Americans seeking work as it is.

You can break the amount of demand in the economy up into bigger chunks — fewer, more traditional jobs with high pay — or into smaller chunks — more jobs, but with lower pay. But the amount of demand in the economy is the amount of demand in the economy. And right now, as it has generally been over the last few decades, we flat out don't have enough.

Nor does it help much to boost low wages in the gig economy with an increase in the earned income tax credit (EITC), as they suggest, because the EITC effectively defeats itself by subsidizing low-wage business models.

It actually makes it more attractive for businesses to share relatively little of their own internal revenue with workers — and instead shovel most of it to upper management and shareholders — precisely because they know the government will top-off workers' incomes. And this assumes the government will both take in sufficient tax revenue and move enough of it down the income ladder to give gig economy workers a living wage. But people who like work requirements tend to occupy a particular political and ideological tribe. It seems unlikely this same group would be much interested in taxes and transfers on the scale necessary to make the EITC work.

This relates to the last point, which is the question of power. Fundamentally, more power is what workers throughout the economy need: If workers have power, they can bargain for better working conditions and for a bigger cut of their employer's revenue, rendering the EITC unnecessary. Full employment would provide workers that power because it means employers are constantly afraid they will lose their workers to better opportunities and thus are forced to pay well and provide good working conditions. (Welfare programs without work requirements provide power too, by allowing workers to say no to bad employment offers without fear of destitution.)

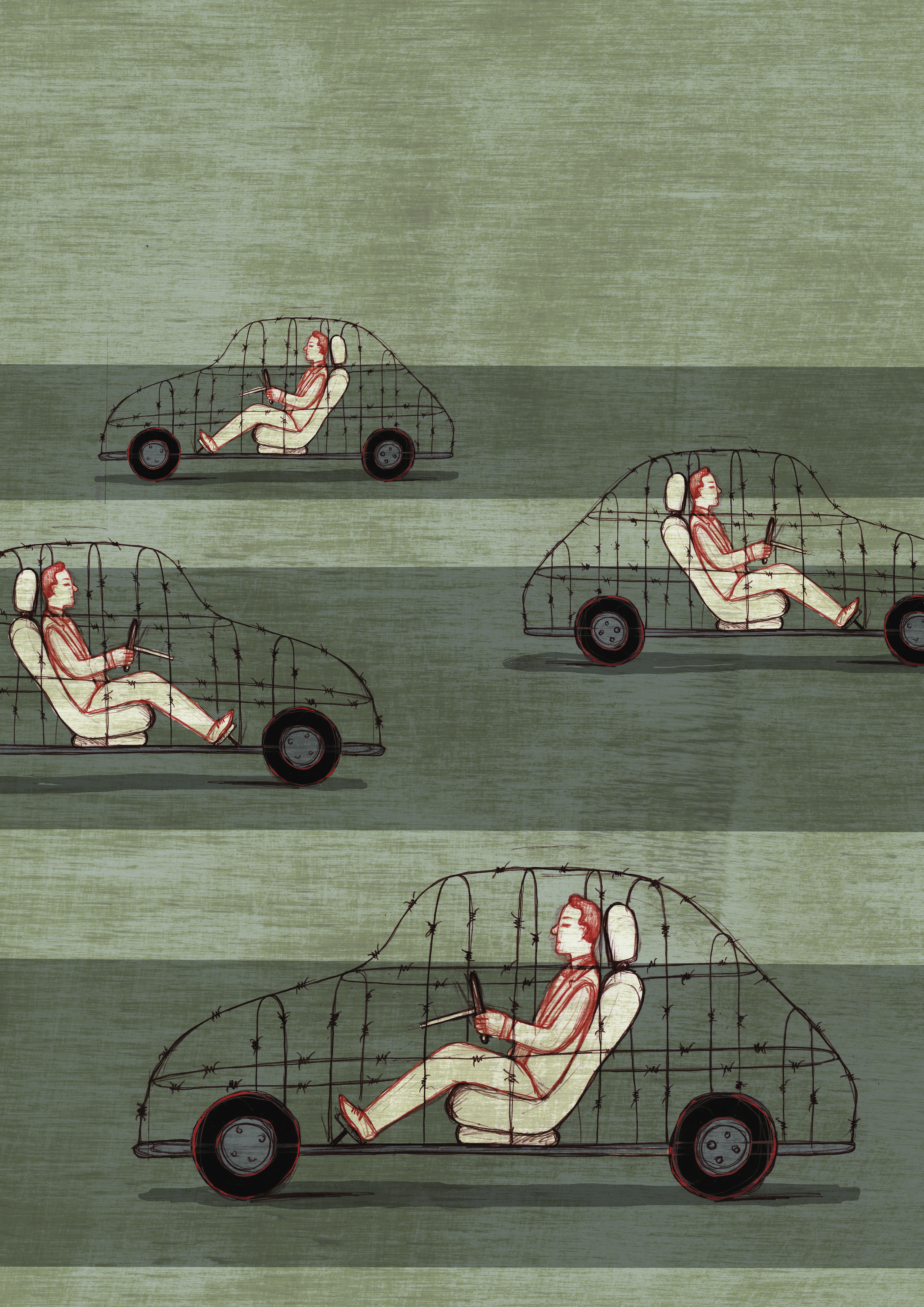

More power is precisely what Uber for welfare can't provide. It's premised upon, and built for, a circumstance in which employers hold all the cards. It does not give workers more power, it merely gives them more options for what to do with the paltry power they have now. It could even worsen their lack of power, because employers' low wages would be subsidized by welfare and EITC payments, even as the government forced workers to take those low-paying jobs on pain of losing their aid.

A better version of Khanna and Conda's idea would combine their government-maintained directory of available jobs with enough loose money and deficit spending to create and maintain full employment, with the recognition that welfare programs themselves are a key tool for boosting demand. The government could also use those same powers to provide many of the jobs directly as the employer of last resort. Then welfare state programs could be left to serve their real purposes, free of work requirements.

In the end, it boils down to a simple question: Are people on government aid failing society, or has society failed them? Khanna and Conda (and many others in American politics) answer that it's the first. And that's probably their most fundamental error.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.