A brief history of body odor

Humans have always smelled a bit funky, but our conception of "clean" has changed dramatically over the centuries

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In today's highly deodorized world, we assume that to be without smell is to be clean. But throughout the long and pungent history of humanity, smelling "good" has been as delightful as it has sometimes been disgusting.

To get to the root of body odor, you have to start with sweat. But human sweat by itself typically barely smells at all. "The problem is that bacteria living on our body like to eat some of the compounds that come out in our sweat," says journalist Sarah Everts, who's conducted extensive research on the science of perspiration. Eccrine glands, all over the body, and apocrine glands, found mostly in the armpit and genital areas, secrete various compounds that are consumed by bacteria, which in turn release molecules with a smell we recognize as body odor.

Of course, humans were unaware of such compounds throughout most of recorded history, which is why the first efforts to smell civilized consisted of smothering the odors with more favorable scents. "The ancient Egyptians applied concoctions made of ostrich eggs, tortoiseshell, and gallnuts to help improve their personal body pong," Everts says. Fragrances made during this time were often worn on the head, neck, and wrists as thick pastes, or as oil-based salves incorporating ingredients from fragrant plants like cardamom, cassia, cinnamon, lemongrass, lily, myrrh, and rose.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Egyptians also burned fragrant incense and developed jewelry that incorporated scented materials, a tradition still practiced by cultures throughout northern Africa. Hieroglyphics depict men and women wearing small cones atop their wigs that are believed to have been made of perfumed wax and animal fats.

In ancient Greece and Rome, aromatic spices and perfumes gained traction as coveted luxury goods, spreading along trade routes between the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The earliest known perfumeries date to the Roman Empire, a rare period in history when it was normal to bathe daily, both as a social custom and for religious purposes. Following a soak, the body was typically anointed with scented oils, and these salves were sometimes carried in small bottles tied around the wrist.

Early fragrance concoctions incorporated floral scents like jasmine, rose, iris, lavender, violet, or chamomile, as well as spicy smells from natural materials such as yellow amber, camphor, and cloves. Perfumes derived from animals included civet (from civet cats), musk (found in musk deer), or ambergris (a secretion of the sperm whale). Scented powders made from talc were carried in fabric sachets, and garments were sewn from fabrics steeped in perfume.

By the 5th century A.D., scented oils and incense had become entwined with religious rituals across Europe, including those of Judaism and Christianity. The mixing of various social classes at public worship spaces meant that everyone brought their own particular smells, and incense helped to mask the God-fearing funk. "Priests were so overwhelmed by the stench of their worshipers that they would avidly burn incense to counteract the worshipers' body odor," Everts says.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even while the clergy were exalting religious incense, they sometimes derided perfume as a sinful indulgence. For several centuries, many Christians rejected bathing for its connection to the sin of pride or vanity.

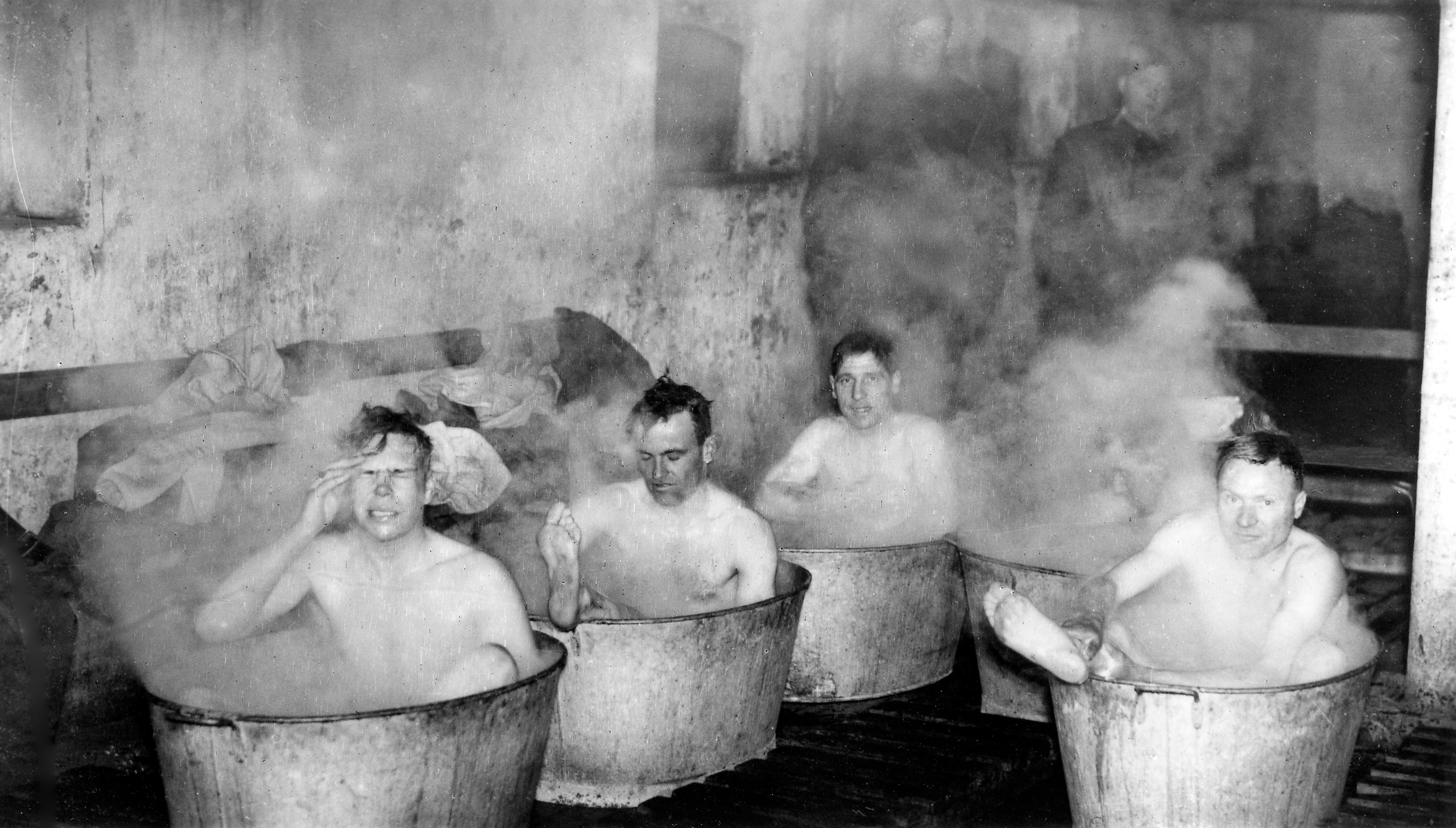

While Christians preferred not to wash, Islamic communities kept the tradition of bathing alive. In the eastern part of the Byzantine Empire, Roman bathing customs evolved into the hammam, or Turkish bath. Around the 11th century, the return of Crusaders brought the hammam tradition back to Europe along with scented treasures like musk and civet.

At the time, most soaps were rough and smelled like the ash and animal fats they were made from, so they were rarely used on the skin. But then Middle Eastern inventors developed better formulas incorporating vegetable oils, and soap making became the primary application for perfumes.

By the 13th century, chemists had mastered the art of distilling, in which a natural substance is boiled in water, extracting its essential oil. Inventors combined these essential oils with alcohol to create the stable, quick-drying perfume that we know today. The first major alcohol-based fragrance was a late-14th-century rosemary perfume known as Hungary water, since it was designed for Queen Elisabeth of Hungary.

Most of Europe's public bathhouses had been closed because of the bubonic plague, which killed more than a third of the population. Without a scientific understanding of germs, people believed that diseases like the plague were contagious through the air.

Thus the stinking smell of sickness was fought with the sweet scent of aromatics. "Specific diseases, like plague, believed to be conveyed by impure or corrupt air, were frequently countered by building bonfires in public spaces, and in private by burning incense or inhaling perfumes such as rose and musk," says Jonathan Reinarz, a professor of medical history who published a book called Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell. Small bouquets of herbs and flowers called posies, nosegays, or tussie-mussies became popular accessories carried to overcome the stench of death.

Meanwhile, the true antidote to major epidemics — better hygiene via bathing and hand washing — was unattainable as long as most Europeans believed that bathing was dangerous to one's health. In the 15th and 16th centuries, prominent scientists helped spread the false idea that water's ability to soften skin and open pores actually weakened the flesh. With this in mind, the few who did bathe regularly took special precautions, like anointing the body with oil and wrapping themselves in a scented cloth. Hair could be rubbed with aromatic powders, and bad breath was improved by chewing pungent herbs.

As more refined herbal or floral scents became trendy, France came to dominate the international perfume industry. One of its most popular fragrances was eau de cologne, a recipe originally produced as protection against the plague, which included rosemary and citrus essences suspended in a grape-based spirit.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the French aristocracy took perfumery to a new level, installing scented fountains at their dinner parties and making their own custom essences. Leather gloves infused with neroli, an orange-blossom fragrance, were one of the country's most successful products.

Small scent boxes designed to hold liquid perfumes soon became the accessory of the moment. Called "smelling boxes," "pouncet boxes," and, later, "vinaigrettes," these decorative perforated cases held small sponges or fabric swatches soaked with alcohol- or vinegar-based fragrances hailed for their medicinal qualities, which also worked to defend against unpleasant odors encountered on city streets.

Yet even with access to perfumes, wealthy people often still stank. "Descriptions of Versailles by a lot of people visiting the court of Louis XVI and his bride, Marie Antoinette, just before the revolution are really striking," Reinarz says. "They described it as a stinking cesspit."

During the French Revolution, clothing styles shifted toward simpler silhouettes, fewer layers, and lighter fabrics made from cotton, which could also be more easily washed. Bathing had finally come back into vogue, as doctors now believed that accumulated filth prevented the body from releasing corrupt fluids.

Outbreaks of cholera in the mid-1800s inspired cities across Europe to improve their sanitation by expanding access to fresh water, systematizing garbage disposal, and constructing new sewer systems. As better hygiene took over, strong perfumes were no longer essential to combat stench, and their association with the aristocracy was becoming a hindrance to sales, so the industry aligned itself more with fashion.

When perfumes moved from the pharmacy to the cosmetics counter, their use was increasingly linked with the feminine, especially as Victorian-era notions about separate spheres for each gender took hold. While some scents, like tobacco and pine, remained connected to masculinity, the general concept of good smell was increasingly associated with the world of women.

Americans had been as reluctant to bathe as Europeans, but by the late 19th century, the U.S. had adopted novel cleaning devices like showers and toothbrushes, which were supported by the latest studies on hygiene. America's clean regime was also made possible by the young country's abundant space. "Water mains and sewers were more easily installed in new cities than in ancient ones," Katherine Ashenburg writes in The Dirt on Clean. "Houses with bathrooms became the domestic norm, in contrast to Europe's old, crowded apartments."

The earliest successful brand of commercial deodorant was developed in 1888 by an inventor in Philadelphia and dubbed Mum, as in "keeping silent" or "Mum's the word." The first patented version of Mum was sold as a waxy cream that quickly inspired imitations, but these cumbersome products were unpleasant to apply and often left a greasy residue on clothing. In 1903, Everdry introduced the world's first antiperspirant, which used aluminum chloride to clog pores and block sweat. These early antiperspirants were highly acidic, so they, too, often damaged clothing, and left the wearer with a stinging sensation.

Early in the 20th century, a Cincinnati surgeon wanted his hands sweat-free while operating, so he invented an antiperspirant called Odo-Ro-No. In 1912, his daughter Edna Murphey hired an ad agency to boost the company's sales, and their first successful ad positioned excessive sweating as a medical disorder. A few years later, the company tried a new tack: convincing self-conscious women that their body odor (which it dubbed B.O. for short) was a problem nobody would directly tell them about.

Similar campaigns were soon waged against every imaginable imperfection, whether it was flawed makeup, gray hair, torn stockings, acne, underarm hair, bad breath, or the ultimate — bad "feminine hygiene." To describe the "life-destroying" impact of bad breath, an oral antiseptic brand called Listerine coined the now ubiquitous phrase "Often a bridesmaid, but never a bride."

By the 1930s, American deodorant companies had secured a female customer base, so they began including subtle advertising copy referencing men's body odor. In 1935, Top-Flite, the first deodorant targeted at men, hit store shelves in its sleek black bottle, followed by other stereotypically male designs, like the Seaforth bottle resembling a miniature whiskey jug. Advertisements for men's deodorant products often focused on financial insecurities, positing that foul body odors might ruin one's career.

Meanwhile, the delivery method of deodorant was shifting from messy creams to more pleasant roll-on sticks, like the 1940s applicator developed by Mum employee Helen Diserens, based on the design of a ballpoint pen. In the early 1960s, Gillette introduced Right Guard, the first aerosol antiperspirant.

Today, we're bombarded with a cornucopia of deodorants, antiperspirants, soaps, colognes, perfumes, and douches, all aiming to eradicate smells associated with the human body — even if those odors are the result of healthy processes. "I think my favorite weird patent was based on baker's yeast," Everts says. "I just don't think I'd want to put baker's yeast in my armpit."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in CollectorsWeekly.com. Reprinted with permission.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict