How Facebook became so profitable

Why is Facebook soaring while "its biggest rivals stumble"? Here's what you need to know.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The smartest insight and analysis, from all perspectives, rounded up from around the web:

"Facebook is killing it," said Julia Greenberg at Wired. In a week in which tech giants like Apple, Google, and Twitter posted surprisingly disappointing earnings, the world's biggest social network "wildly beat Wall Street's expectations," tripling its first-quarter profit compared with last year — to $1.5 billion on $5.3 billion in revenue — and sending its stock to an all-time high. Why is Facebook soaring while "its biggest rivals stumble"? Like Alphabet (née Google), Facebook spends lavishly on "moonshot ventures" like drones and virtual reality. And like Apple, it relies on a legacy product — its newsfeed — to drive the bulk of its earnings. But more than any other giant in Silicon Valley, Facebook has "skillfully transitioned" its advertisers into buying placements "where most users are likely to see them: on their phones."

"Facebook is in a class of its own," especially when it comes to mobile ads, said Tenzin Pema and Supantha Mukherjee at Reuters. The company now reaches 1.65 billion people around the world every month, and mobile advertising makes up 82 percent of the firm's total revenue, up from 73 percent last year. Our addiction to checking Facebook is making the company "astonishingly profitable," said Peter Eavis at The New York Times. Users spent an average of 17 minutes per session on the social network in March, but only nine minutes on Google, according to SimilarWeb. That lingering is what makes Facebook such an attractive place for advertisers. What's the going rate to "catch your attention as you argue with your friends and relatives over Donald Trump or coo over baby pictures"? In the first quarter alone, Facebook pulled in $11.86 in ad revenue per user in the U.S. and Canada.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

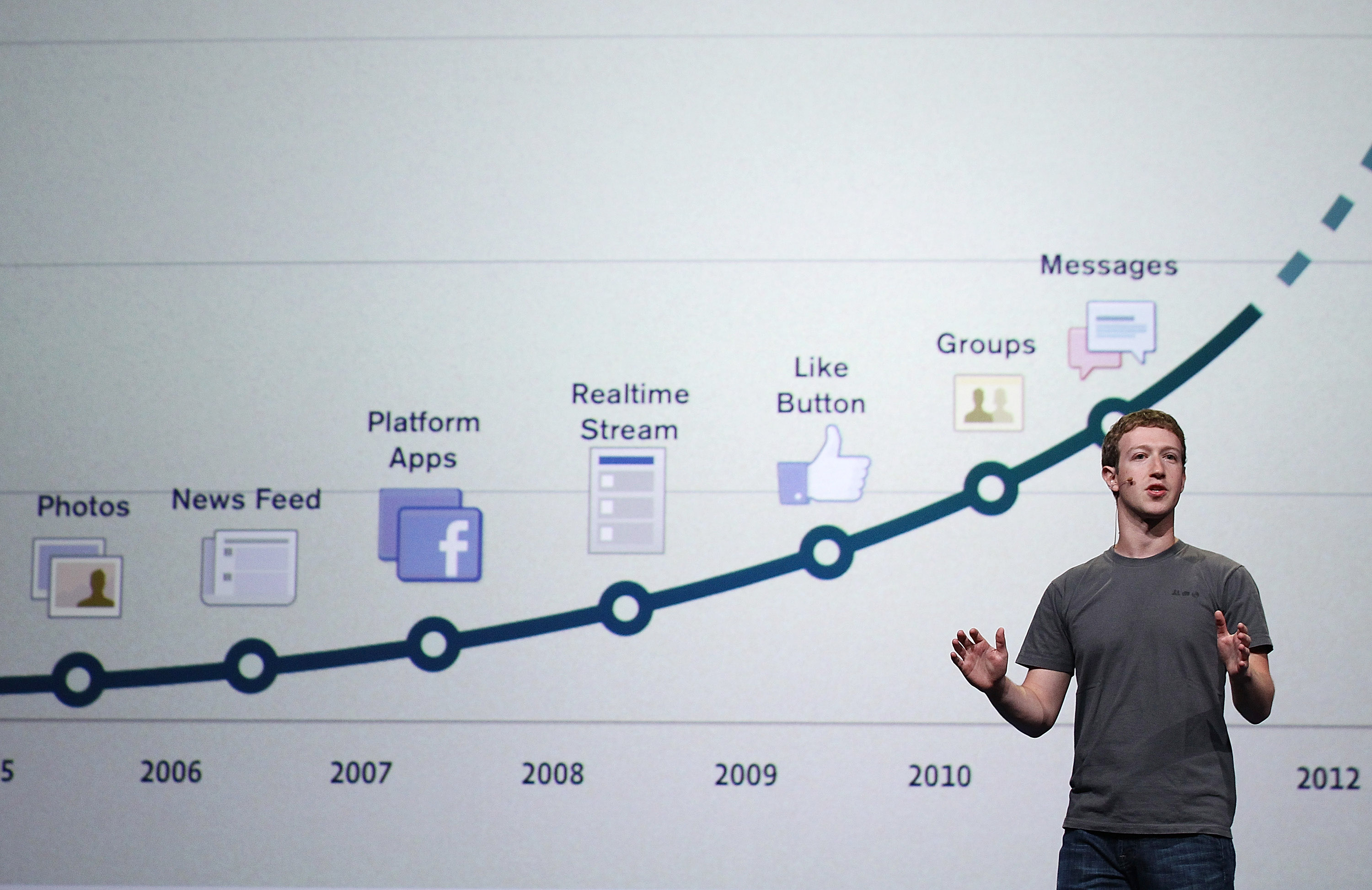

Oddly enough, Facebook may have "peaked" as a social network, said Will Oremus at Slate. People are actually sharing fewer posts about their personal lives. But the company "has been quietly yet aggressively preparing for exactly this sea change." Its $1 billion acquisition of Instagram in 2012 and the $22 billion purchase of WhatsApp two years later were "widely mocked" at the time. But now most online socializing happens in photo-sharing and messaging apps, and Facebook owns two of the biggest ones. As for Facebook proper, its content expands far beyond personal updates — to include news, video, and games — but the feed is still ranked by what you and your friends like and share. Instead of a true social network, it has become "a personalized portal to the online world."

Things are going so well that Facebook last week "announced a little present for Mark Zuckerberg," said Matt Levine at Bloomberg. The company will create a new class of common stock that allows him to maintain authority as long as he is CEO. Under the proposal, Zuckerberg will be able to give away most of his shares to philanthropic causes — as he has said he will do — without losing voting control. It will also insulate him "from any shareholder pressure to rein in his ambitions." Among those: "helping to cure all diseases by the end of this century." Crazy as it sounds, investors seem willing to follow Zuckerberg wherever he goes. So far, that strategy has made them "a lot of money."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy