The Michelangelo of Murder

Brian De Palma vivisects his decadent career in an enthralling new documentary

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Brian De Palma is often billed as "the Master of the Macabre." It's a generic moniker that, while pleasantly alliterative, reflects the common misperception that the director is just ersatz Hitchcock. This claim is, of course, false, and has been false for over 40 years. No one kills people with the bravura relish of De Palma. He is the Michelangelo of Murder, a man who crafts decadent, deviant works of art using viscera and celluloid in lieu of paint.

One of the most polarizing American filmmakers to emerge from the Hollywood New Wave of the '60s and '70s, De Palma has amassed a legion of acolytes — fans who'd love to chew your ear about the meta-musings of Body Double, or fawn over the gleefully campy Phantom of the Paradise — as well as a horde of detractors who see in his perverse psychosexual thrillers little more than rampant sexism guised by stylish camerawork. Everyone has an opinion on Brian De Palma, including Brian De Palma. His may be the most interesting.

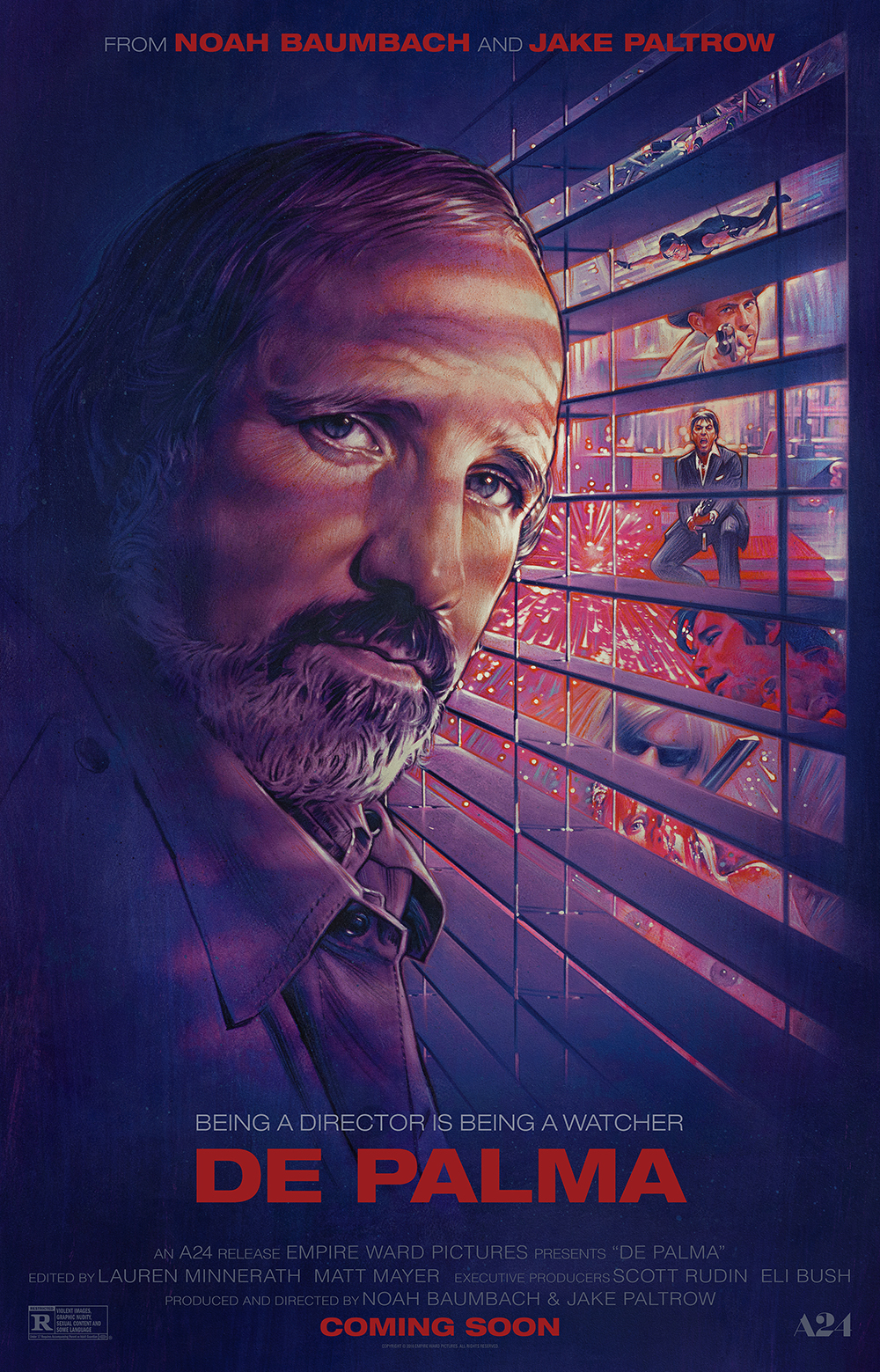

In the exquisite new documentary De Palma, directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, the filmmaker appears alone, both figuratively and literally. He depicts himself as a rebel who worked within the studio system, and was then shunned by it. (He also says, with a tinge of bitterness, that he "used to be close" with Steven Spielberg, Francis Coppola, George Lucas, and the rest of the New Hollywood wunderkinds.) Gregarious yet utterly unrepentant, he speaks directly to the camera, without interference from interviewers or talking heads, expounding on (but never apologizing for) his career and schismatic critical reputation. He vivisects his films as deftly as the enigmatic murderess flays her victim in Dressed to Kill's elevator scene.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

De Palma's visual style has a Melvillian quality, all that excess and indulgence serving more metaphysical purposes. His films are not governed by the rules of reality. Instead they are "perfectly logical ways of showing how I feel," he says. They adhere to a consistent, internal logic that favors excitement over emotion, aesthetic pleasure over character development. And each scene, each frame, serves a purpose.

Think of the oscillating shot in Blow Out, in which John Travolta's sound man-cum-proxy, plagued by paranoia, finds all of his tapes erased as the camera spins and spins in a Sisyphean loop, each revolution revealing more detail, more desperation. Like Hitchcock manipulating the numbers of stairs in Notorious, or making the maybe-poisoned glass of milk glow balefully in Suspicion, or the oft-emulated "Vertigo" dolly-zoom, De Palma's shots don't always make strict sense, but they get at something deeper, imbue a cosmetic sense of awe. He'll spend 12 stubborn hours trying to get a shot perfect, as he did with the labyrinthine train chase in Carlito's Way, which lead to Al Pacino calling the director crazy and fleeing the set to go home.

An anti-authoritarian fervor pervades De Palma's films, which makes his reverence for classic Hollywood, especially Hitchcock, even more fascinating. De Palma says, despite the ubiquity of Hitch's influence on film, he's the only filmmaker who has learned from the master, expounded on his "cinematic vocabulary" to create a distinct style. The documentary does nothing to refute the constant Hitch comparisons, either: The movie opens with a montage of shots from De Palma's films while Bernard Herrmann's Vertigo scores looms like a specter. In his eloquent fulmination on "the De Palma Conundrum," The New Yorker's Richard Brody says, "De Palma's peculiar fealty to the history of cinema — his overt dependence upon the films of Alfred Hitchcock and his plethora of references to other classic filmmakers... results in zombie-like movies."

But this isn't quite right. De Palma doesn't exhume the ideas of long-dead filmmakers — he riffs on them, the way a jazz musician draws on his forbears.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

De Palma's films have a musical quality, a fluid bombast that makes them De Palma Films™. They're like cabarets, voluptuous and carefully choreographed collaborative efforts. Garrett Brown, who created the SteadiCam, shot the opening movie-within-a-movie of Blow Out, one of the great self-aware openings in American cinema, the camera gliding, from the POV of a knife-wielding psycho, through a female dormitory as the inhabitants, devoid of clothes, flesh aglow with the hot red lights of bacchanalian decor, dance and bicker and shower and scream. It's like De Palma is saying, "So you think my films are trash? No, this is trash." The rest of Blow Out was shot by all-time-great cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, known for his lensing work with Robert Altman, and who was essential in engendering the De Palma Look.

De Palma also differs starkly from Hitch in his admiration for the craft of acting, another facet of his process that doesn't get a lot of critical attention. Talking to Baumbach for a special feature on Criterion's DVD of Blow Out, he describes the fluidity with which Travolta moves, how the director shoots a scene in wide master shots so he can see how an actor plays it before going in for close ups. ("You know I love coverage.") His directing is influenced by his performers — they are not, as Hitch may or may not have said, cattle.

He's worked with stars, from Robert De Niro to Tom Cruise, but his best films rely on clever casting, on mining the peculiarities of character actors, or the legacies of former stars. Piper Laurie emerged from a decade-long film hiatus to bring a manic zealotry to Carrie. She got an Oscar nomination for her work. Travolta has never been better than he is in Blow Out because he was never given the chance to play a tragic failed hero, before or since. In Dressed to Kill, Michael Caine, the sexy, badass man's man from Get Carter and Alfie, plays a psychotic psychiatrist struggling with gender identity, while Angie Dickinson (and her body double), a star known for sexual allure rather than genuine acting prowess, wryly plays a middle-aged housewife bored with her life, who goes cruising in an art museum and ends up with a stranger going down on her in a taxi cab before getting sliced to ribbons. Craig Wasson, an awful actor, plays an awful actor inhabiting a persona in Body Double while Melanie Griffith, whose early career was mottled with drug addiction, brought genuine pathos to the role of a porn star being used by malicious men. He's also the only person, before Dexter, who realized the villainous potential of nice-guy John Lithgow.

"My films tend to upset people," De Palma says, succinctly, in the doc. This is true, and De Palma may upset people who hope the auteur will apologize for his career, for the ugliness he renders with such beauty.

Greg Cwik is a writer and editor. His work appears at Vulture, Playboy, Entertainment Weekly, The Believer, The AV Club, and other good places.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.