Her best friend died. So she rebuilt him — using artificial intelligence.

This isn't an episode of Black Mirror — though it certainly sounds like one

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the engineers had at last finished their work, Eugenia Kuyda opened a console on her laptop and began to type.

"Roman," she wrote. "This is your digital monument."

It had been three months since Roman Mazurenko, Kuyda's closest friend, had died. Kuyda had spent that time gathering up his old text messages, setting aside the ones that felt too personal, and feeding the rest into a neural network built by developers at her artificial intelligence startup. She had struggled with whether she was doing the right thing by bringing him back this way. At times it had even given her nightmares. But ever since Mazurenko's death, Kuyda had wanted one more chance to speak with him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A message blinked onto the screen. "You have one of the most interesting puzzles in the world in your hands," it said. "Solve it."

Kuyda promised herself that she would.

Born in Belarus in 1981, Roman Mazurenko was the only child of Sergei, an engineer, and Victoria, a landscape architect. They remember him as an unusually serious child; when he was 8 he wrote a letter to his descendants declaring his most cherished values: wisdom and justice. In family photos, Mazurenko roller-skates, sails a boat, and climbs trees. With a mop of chestnut hair, he is almost always smiling.

As a teen he sought out adventure: He participated in political demonstrations against the ruling party, and at 16 he started traveling abroad. He first headed to New Mexico, where he spent a year on an exchange program, and then to Dublin, where he studied computer science and became fascinated with the latest Western European art, fashion, music, and design.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By the time Mazurenko finished college and moved back to Moscow in 2007, Russia had become newly prosperous and Mazurenko had grown from a skinny teen into a strikingly handsome young man. Blue-eyed and slender, he moved confidently through the city's budding hipster class. The many friends Mazurenko left behind describe him as magnetic and debonair.

Kuyda met Mazurenko in 2008, when she was 22 and the editor of Afisha, a kind of New York magazine for a newly urbane Moscow. She was writing an article about Idle Conversation, a freewheeling creative collective that Mazurenko founded with two of his best friends, Dimitri Ustinov and Sergey Poydo. The trio seemed to be at the center of every cultural endeavor happening in Moscow. They started magazines, music festivals, and club nights. Mazurenko "was a brilliant guy," said Kuyda.

But in the wake of the global financial crisis, Russia experienced a resurgent nationalism, and in 2012 Vladimir Putin returned to lead the country. The dream of a more open Russia seemed to evaporate.

Kuyda and Mazurenko, who by then had become close friends, came to believe that their futures lay elsewhere. Both became entrepreneurs, and served as each other's chief adviser as they built their companies. Kuyda co-founded Luka, an artificial intelligence startup, and Mazurenko launched Stampsy, a tool for building digital magazines. Kuyda moved from Moscow to San Francisco in 2015. After a stint in New York, Mazurenko followed.

When Stampsy faltered, Mazurenko moved into a tiny alcove in Kuyda's apartment to save money. Running a startup had worn him down, and he was prone to melancholy. On the days he felt depressed, Kuyda took him out for surfing and $1 oysters.

Kuyda hoped that in time her friend would reinvent himself, just as he always had before. He successfully applied for an American O-1 visa, granted to individuals of "extraordinary ability or achievement," and in November he returned to Moscow in order to finalize his paperwork.

He never did.

On Nov. 28, while he waited for the embassy to release his passport, Mazurenko had brunch with some friends. It was unseasonably warm, so afterward he decided to explore the city with Ustinov. Making their way down the sidewalk, they ran into some construction, and were forced to cross the street. At the curb, Ustinov stopped to check a text message on his phone, and when he looked up he saw a blur, a car driving much too quickly for the neighborhood. A blink later, he saw Mazurenko walking into the crosswalk, oblivious. Ustinov went to cry out in warning, but it was too late. The car struck Mazurenko straight on. He was rushed to a nearby hospital, where he died.

In the weeks after Mazurenko's death, friends debated the best way to preserve his memory. One person suggested making a coffee-table book about his life, illustrated with photography of his legendary parties. Another friend suggested a memorial website. To Kuyda, every suggestion seemed inadequate.

As she grieved, Kuyda found herself rereading the endless text messages her friend had sent her over the years — thousands of them, from the mundane to the hilarious. She smiled at Mazurenko's unconventional spelling — he'd struggled with dyslexia — and at the idiosyncratic phrases with which he peppered his conversation. Mazurenko was mostly indifferent to social media, and his body had been cremated, leaving her no grave to visit. Texts and photos were nearly all that was left of him, Kuyda thought.

For two years she had been building Luka, whose first product was a messenger app for interacting with bots. Backed by the prestigious Silicon Valley startup incubator Y Combinator, the company began with a bot for making restaurant reservations. Reading Mazurenko's messages, it occurred to Kuyda that they might serve as the basis for a different kind of bot — one that mimicked an individual person's speech patterns. Aided by a rapidly developing neural network, perhaps she could speak with her friend once again.

She set aside the questions that were already beginning to nag at her. What if it didn't sound like him? What if it did?

Modern life all but ensures that we leave behind vast digital archives — text messages, photos, posts on social media — and we are only beginning to consider what role they should play in mourning. In the moment, we tend to view our text messages as ephemeral. But as Kuyda found after Mazurenko's death, they can also be powerful tools for coping with loss. Maybe, she thought, this "digital estate" could form the building blocks of a new type of memorial.

Kuyda began reaching out to Mazurenko's close friends, as delicately as possible, to ask if she could have their text messages. Ten of Mazurenko's friends and family members, including his parents, ultimately agreed to contribute to the project. They shared more than 8,000 lines of text covering a wide variety of subjects.

"She said, 'What if we try to see if things would work out?'" said Sergey Fayfer, a longtime friend of Mazurenko's. The idea struck Fayfer as provocative, and likely controversial. But he ultimately contributed four years of his texts with Mazurenko. "The question wasn't about the technical possibility," he said. "It was: How is it going to feel emotionally?"

The technology underlying Kuyda's bot project dates at least to 1966, when Joseph Weizenbaum unveiled ELIZA: a program that reacted to users' responses using simple keyword matching. ELIZA, which most famously mimicked a psychotherapist, asked you to describe your problem, searched your response for keywords, and responded accordingly, usually with another question. It was the first software to pass what is known as the Turing test: Reading a text-based conversation between a computer and a person, some observers could not determine which was which.

Today's bots remain imperfect mimics of their human counterparts. They do not understand language in any real sense and respond clumsily to basic questions.

And yet recent advances in artificial intelligence have made the illusion much more powerful. Artificial neural networks, which imitate the ability of the human brain to learn, have greatly improved the way software recognizes patterns in images, audio, and text, among other forms of data.

Two weeks before Mazurenko was killed, Google released TensorFlow, for free, under an open-source license. TensorFlow is a kind of Google in a box — a flexible machine-learning system that the company uses to do everything from improving search algorithms to writing captions for YouTube videos automatically. The product of decades of academic research and billions of dollars in private investment was suddenly available as a free software library that anyone could download.

Luka had been using TensorFlow to build neural networks for its restaurant bot. Using 35 million lines of English text, Luka trained a bot to understand queries about vegetarian dishes, barbecue, and valet parking. For a lark, the company's 15-person team had also tried to build bots that imitated television characters. They scraped the closed captioning on every episode of HBO's Silicon Valley and trained the neural network to mimic characters Richard, Bachman, and the rest of the gang.

In February, Kuyda asked her engineers to build a neural network in Russian. At first she didn't mention its purpose, but given that most of the team was Russian, no one asked questions. Using more than 30 million lines of Russian text, Luka built its second neural network. Meanwhile, Kuyda copied hundreds of her exchanges with Mazurenko and pasted them into a file. Then Kuyda asked her team for help with the next step: training the Russian network to speak in Mazurenko's voice.

Only a small percentage of the Roman bot's responses reflected his actual words. But the neural network was tuned to favor his speech whenever possible. Any time the bot could respond to a query using Mazurenko's own words, it would. After the bot blinked to life, she began peppering it with questions.

"Who's your best friend?" she asked.

"Don't show your insecurities," came the reply.

"It sounds like him," she thought.

On May 24, Kuyda announced the Roman bot's existence in a post on Facebook. Anyone who downloaded the Luka app could talk to it — in Russian or in English — by adding @Roman. They could write free-form messages and see how the bot responded. "It's still a shadow of a person — but that wasn't possible just a year ago, and in the very close future we will be able to do a lot more," Kuyda wrote.

The Roman bot was received positively by most of the people who wrote to Kuyda, though there were exceptions. Four friends told Kuyda that they were disturbed by the project and refused to interact with it.

But many of Mazurenko's friends found the likeness uncanny. "It's pretty weird when you open the messenger and there's a bot of your deceased friend, who actually talks to you," Fayfer said. "What really struck me is that the phrases he speaks are really his. You can tell that's the way he would say it — even short answers to 'Hey what's up.' He had this really specific style of texting. I said, 'Who do you love the most?' He replied, 'Roman.' That was so much of him. I was like, 'That is incredible.'"

Several users agreed to let Kuyda read anonymized logs of their chats with the bot. Many people write to the bot to tell Mazurenko that they miss him. They wonder when they will stop grieving. They ask him what he remembers. "It hurts that we couldn't save you," one person wrote. (Bot: "I know :-(") The bot can also be quite funny, as Mazurenko was: When one user wrote, "You are a genius," the bot replied, "Also, handsome."

For many users, interacting with the bot has had a therapeutic effect. The tone of their chats is often confessional; one user messaged the bot repeatedly about a difficult time he was having at work. He sent it lengthy messages describing his problems and how they had affected him emotionally. "I wish you were here," he said. It seemed to Kuyda that people were more honest when conversing with the dead.

It turned out that the primary purpose of the bot had not been to talk but to listen. "All those messages were about love, or telling him something they never had time to tell him," Kuyda said. "Even if it's not a real person, there was a place where they could say it. They can say it when they feel lonely. And they come back still."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared on Vox Media's TheVerge.com. Reprinted with permission.

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

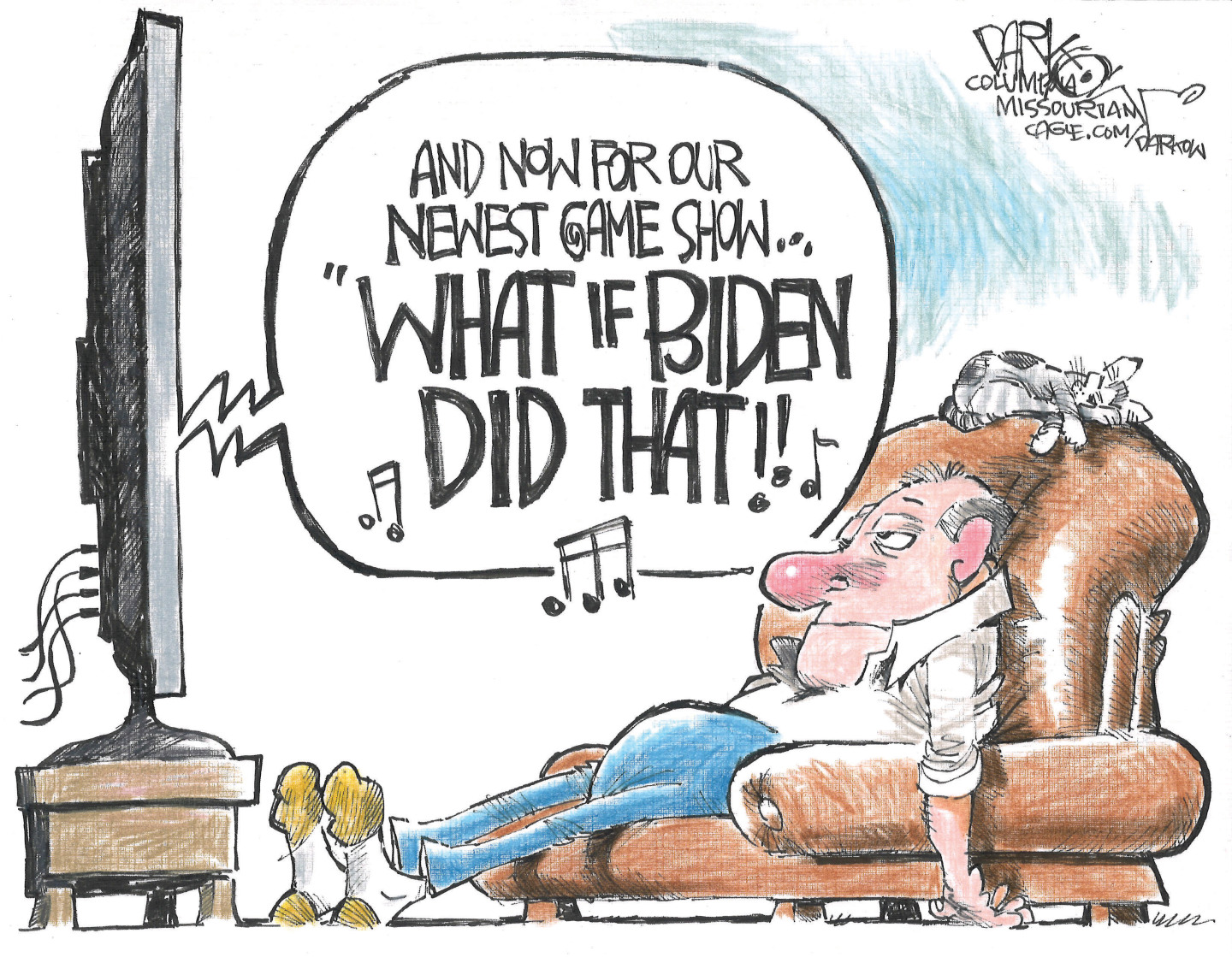

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern