There's never been a better time to watch Dirty Dancing

Released 30 years ago this week, the film is far more politically radical than you remember

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1987, Americans flocked to a movie about the forbidden love between a young Jewish radical and a male prostitute. Dirty Dancing, which was released 30 years ago this week, is often remembered as nothing more than a teenybopper classic, and lumped in with other offerings of the time like Footloose and Flashdance and Fame: MTV-era musicals about characters who danced their problems away. But Dirty Dancing is also one of the most highly politicized movies ever to achieve success among mainstream teenage audiences. It was so successful, in fact, that its status as a classic now easily eclipses its subject matter — and the reasons it still offers something to today's young viewers that few movies since have even attempted to provide.

Frances "Baby" Houseman (Jennifer Grey), a liberal but sheltered young doctor's daughter, comes to a Catskills resort with her family, expecting to kill time before starting her first semester at Mt. Holyoke in the fall. "That was the summer of 1963," her voiceover tells us in the first few moments. "When everybody called me Baby, and it didn't occur to me to mind. That was before President Kennedy was shot, before the Beatles came, when I couldn't wait to join the Peace Corps, and I thought I'd never find a guy as great as my dad. That was the summer we went to Kellerman's."

At Kellerman's, there's an unofficial but immediately clear divide between the resort's regular staff — nice Jewish boys who are instructed, in no uncertain terms, to romance all the nice Jewish girls visiting with their families — and the entertainment staff, some of whom are non-white, all of whom are working class, and who dance with the kind of sexual abandon that most nice Jewish girls had yet to experience in 1963, at least if Baby's reaction is any indication. Baby sneaks into the entertainment staff's after-hours party (to reach the enchanted kingdom, you must carry a watermelon), and becomes fascinated by both Johnny (Patrick Swayze) and Penny (Cynthia Rhodes).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The movie could have progressed very easily from this point without deviating from the romantic comedy playbook at all. Baby and Johnny have to spend time together so their enmity can turn to attraction — let's put them together and have them rehearse a dance. Doing that would mean taking Penny out of the action somehow, but that's standard maneuvering, and there are a million ways to do it: Have her break her leg, rush off to visit a sick relative, even take an accidental overdose.

But Dirty Dancing takes another route. Penny needs an abortion. One of the "nice" boys on staff — a med student who apparently keeps a copy of Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead in his back pocket at all times — has gotten her pregnant, and refuses to take responsibility, saying that "some people count, and some people don't."

Penny needs an abortion so desperately not because she doesn't want to have children — this is never even mentioned as a factor — but because she can't make a living if she can't keep dancing, and she can't keep dancing if she can't have an abortion. Baby borrows money from her father to pay for Penny's abortion, learns to dance with Johnny so she can take Penny's place in a hotel show on the night of the procedure (and falls in love with him, of course — that was a given), and has to reveal the truth to her father anyway, when the "real M.D." who was supposed to provide Penny's abortion turns out to be incompetent, and leaves Penny in agonizing pain. It remains one of the few movies to feature a character deciding to get an abortion and then actually getting one — let alone to show an illegal abortion's horrific aftermath.

Before we return to the romance plot, we linger on the bloodstained sheets of a botched abortion — and the rest of the movie lingers on the pain that comes when we adopt different political perspectives than the people we love.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Dirty Dancing is also a love story about how the personal becomes the political. Baby, liberal in theory (Dirty Dancing may still be the only teen movie whose heroine mentions the Vietnam War twice in the first 10 minutes), becomes radicalized in practice when she confronts the real problems of the working-class people around her.

"I've never known anybody like you," Johnny tells her. "You look at the world and you think you can make it better… You're not scared of anything."

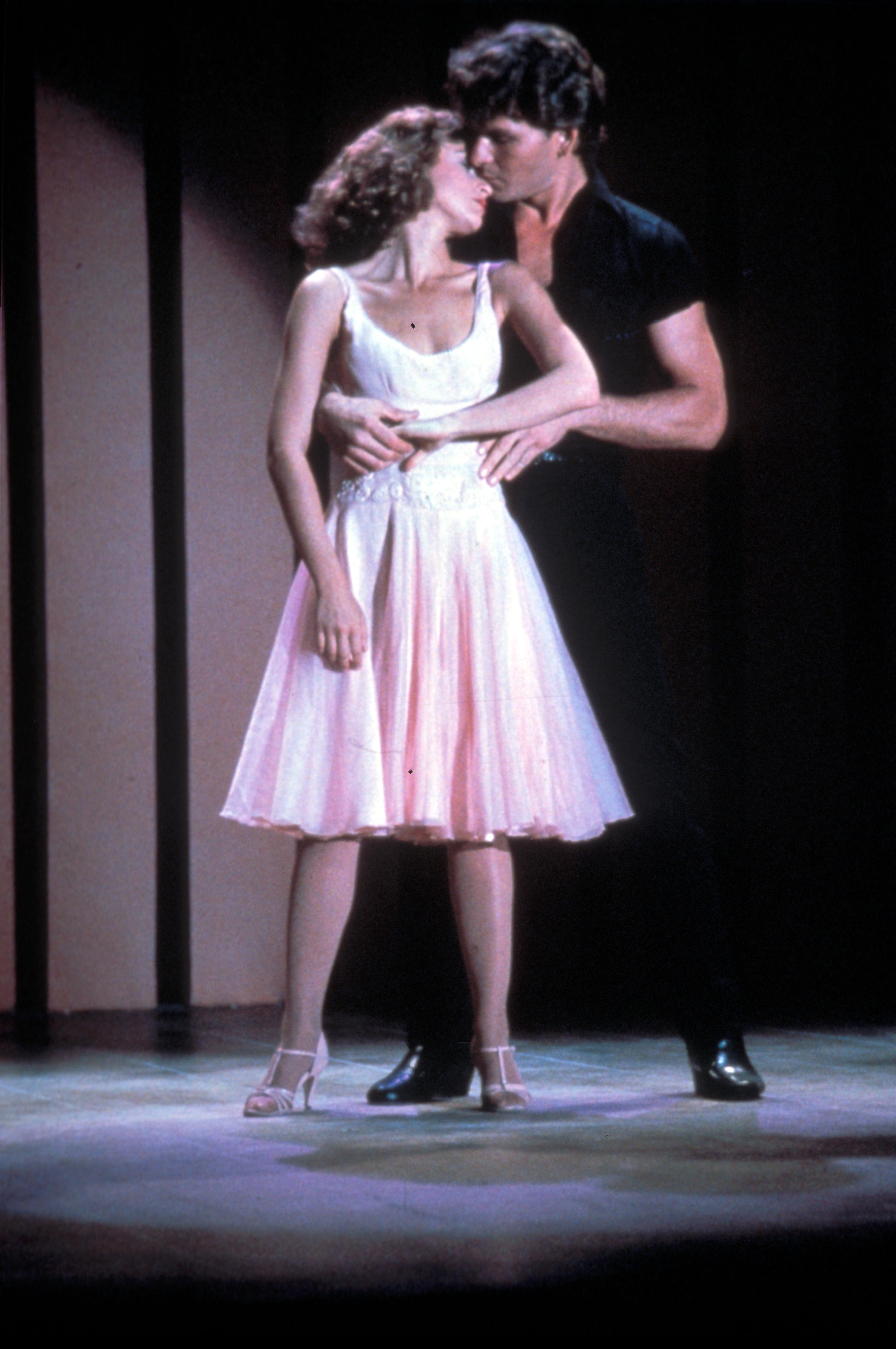

In Dirty Dancing, there's nothing sexier than political empowerment and nothing more romantic than the practice of learning to see beyond class lines — and nothing better able to help others see beyond class lines than romance. In the movie's final scene, the rules of reality loosen, and Johnny and Baby demonstrate their love to the world with a cinematically perfect final dance. This is the fantastic confection that tops a movie whose story has, for the most part, been unusually rooted in reality's harshest details: the closing scene where you are able to show, to everyone, why your love is real, why this man is worth your love, why the people you care for matter, and why the boundaries that hold the people of your world apart can dissolve as soon as we are ready to let them.

And this is where reality gets more complicated. We often expand our political views through personal relationships: There may, in the end, be no more powerful form of political transformation. But sharing these paths with others — helping these worlds to coexist — is often even more difficult. We need to communicate with more than just the power of dance. But Dirty Dancing, for its fantasy trappings, is also a movie that recognizes love as a political act. Today, we can do nothing less.

Sarah Marshall's writings on gender, crime, and scandal have appeared in The Believer, The New Republic, Fusion, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2015, among other publications. She tweets @remember_Sarah.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.