The secret monopoly behind America's outrageous drug prices

Ever heard of "pharmacy benefit managers?"

Most people agree that American drug prices are too high — and it seems to be getting worse. Every month or so there comes yet another story about some holder of a pharmaceutical patent jacking the price up a zillion percent to make a quick buck at the expense of sick people. Martin Shkreli, the hedge fund "pharma bro" who has since been charged with securities fraud, made himself the villainous face of price-gouging doing just that — though Mylan Pharmaceuticals, which pulled the same routine with a device originally developed for the U.S. military, may be an even more stark example.

Yet there is another side to the story, a quintessentially American part of the pharmaceutical supply system that goes largely unnoticed. It involves something called "pharmacy benefit managers," or PBMs, as David Dayen explains in a blockbuster article for the American Prospect. These middleman companies are a major part of why American drug prices are so wildly out of line with the rest of the world.

The details of the PBM architecture are extraordinarily complicated, as Dayen's piece explains. But the basic idea is reasonably straightforward. PBMs date back to the 1960s, when they served as streamlined claims processors to intermediate between pharmacies and drug companies. As the industry grew, PBMs presented themselves as a way to keep drug prices low because they could "form large patient networks, and negotiate discounts from both drug companies and pharmacies, which would have no choice but to contract with them to access the network."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Sounds reasonable enough. But over time, two big things changed: The health-care billing system got more and more hideously complex, and virtually all the PBMs were rolled up into three big companies — ExpressScripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx, which now control a combined 75 to 80 percent of the market. As a result, the promised savings have not materialized. On the contrary, spending on prescription drugs exploded by 1,100 percent between 1987 and 2014, and all three companies — which are each among the top 22 of the Fortune 500 — rake in huge profits. Dayen reports that ExpressScripts' adjusted profit per prescription has increased by 500 percent since 2003.

It's very profitable to abuse your middleman position to extract money from all players — pharmacies, drug companies, insurers, and patients. Market power and kickbacks are used to steer patients to more expensive drugs, a deliberately opaque and Byzantine billing system is used to jack up prices on all parties, especially small pharmacies, and so on. Few can even understand how the system works — only that they're paying through the nose — and those who do can't do anything about it.

It's not a coincidence that two of the big three are associated with other big players in the health-care market. OptumRx is a division of the huge insurer UnitedHealth Group, while CVS Caremark is owned by the CVS pharmacy chain. That in itself is proof positive that a great part of the drug "market" is actually a repressive oligopoly, where the only competition comes from these titanic firms using their economic leverage created by market dominance or vertical integration to force others into doing business with them on their terms. "CVS prescription revenue from Caremark plans nearly tripled in the seven years after the merger," notes Dayen.

But details aside, this is essentially a financial parasite type of activity: Just like Shkreli's hedge fund, PBMs abuse contracts, prices, and control of information to extract profit for doing nothing productive — indeed, actually creating vast net harm.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So what is to be done? Ordinarily, this would be a job for good old anti-trust law, plus government regulation to ensure the creation of a real market for prescription drugs. It is virtually impossible to determine the real price of drugs a huge fraction of the time, because opacity makes it easier for PBMs to rip people off. Government regulations could easily ensure price transparency and prohibit gouging by middlemen — indeed, such policy was tried and tested with huge success long ago in the United States. In this, as in many areas, we have forgotten our own economic history.

And that would surely be a good first step. But it's worth remembering that PBMs only exist in the first place because the rest of the health-care billing system is such a nightmare of complexity. If America were to adopt a "Medicare for all" system, or institute all-payer rate setting mandating Medicare prices for every treatment and drug, PBMs would simply shrink to almost nothing or disappear, and we'd be even better off.

Some monopolies should be broken up. But others shouldn't even exist in the first place. PBMs are in the latter category.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

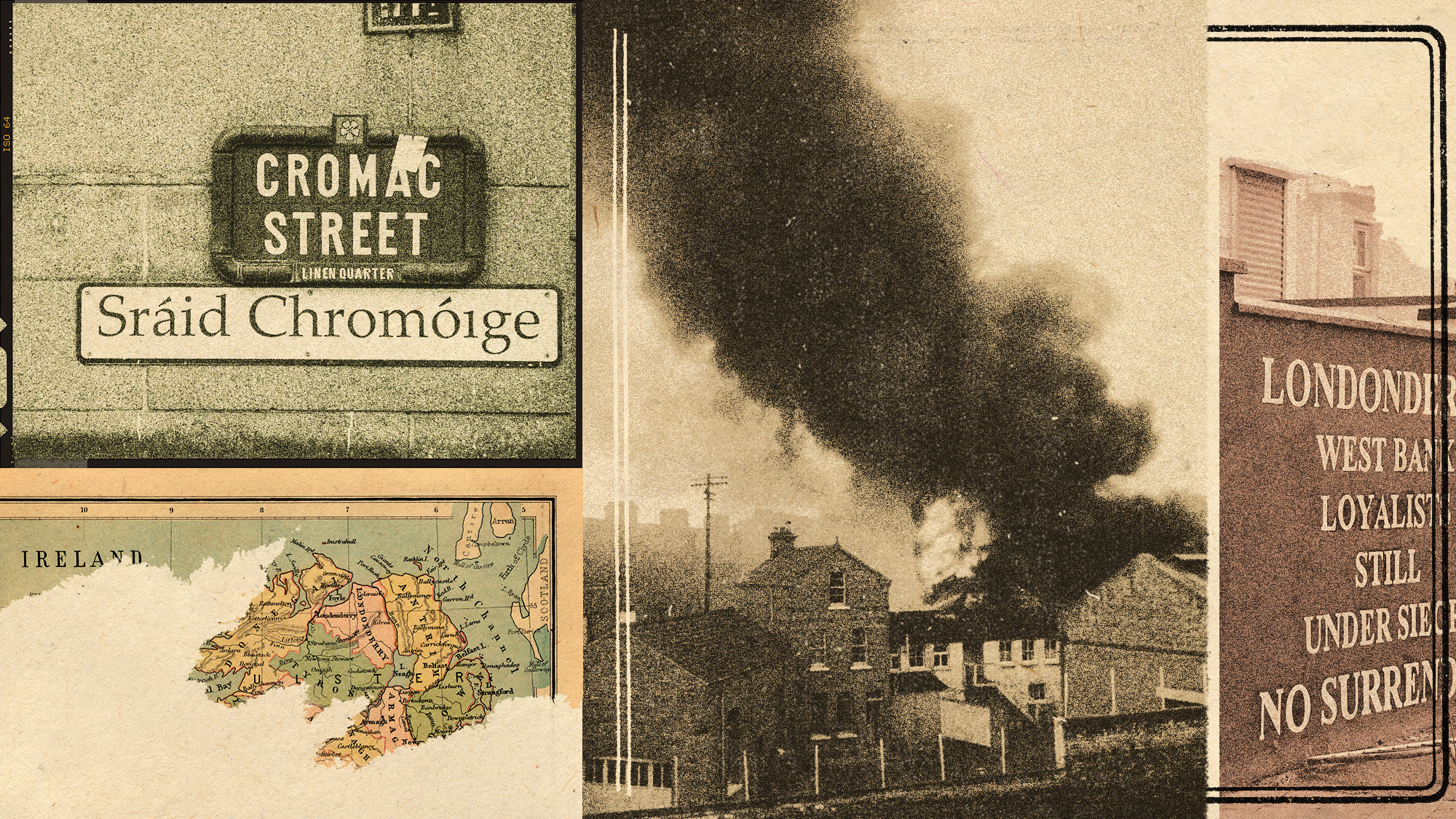

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blog

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blogSpeed Read

-

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.Speed Read

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickers

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickersSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worse

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worseSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attention

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attentionSpeed Read