Blade Runner 2049 is so nostalgic it hurts

This is a stunning film that somehow makes you homesick for the original

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For a futuristic film, Blade Runner 2049 is so nostalgic it hurts. It's nostalgic for Sinatra. It's nostalgic for noir. It's nostalgic for horses and childhood and Elvis and dogs and trees and the sheer existence of memory. It's nostalgic for the version of the future that existed in the past — there are no smartphones, and the Pan Am logo flashes in neon lights. If it's nostalgic for the color green, it's also nostalgic for electricity, which seems to be in short supply. It's nostalgic for snow and bugs and touch. For hedonism when it meant good old American excess like Las Vegas and roulette and whiskey, gigantic statues of naked ladies instead of pornified holograms and geishas.

Above all, it's nostalgic for itself.

That's not exactly new. Ridley Scott's original 1982 Blade Runner — arguably the strangest and most influential sci-fi-noir film of its century, in which Harrison Ford's gritty bounty hunter (or "blade runner," in the film's parlance) hunts down a handful of rogue replicants (essentially, robots who look exactly like people) — created a technological dystopia that practically throbbed with nostalgia for the authenticating power of biology: for organic, carbon-based empirical certainty. "There's some of me in you," genetic designer J.F. Sebastian told the replicants he helped create. It's the kind of thing a proud dad says, and Sebastian is right. Still, as lineages go, this is both accurate and (to replicants trapped in their artificial lifespan) dispiriting. For one thing, there's nothing carnal enough to sustain the human-robot alliance. Sebastian contributed to their creation, sure, but he also peoples his rooms with mechanical beings. The other parental fantasy — the "I am your father" moment in the original film that powers the renegade replicant Roy's confrontation with Dr. Eldon Tyrell, the genius mogul behind the replicants — collapses the moment it's touched. In fact, almost every meaningful measure of what it means to exist short-circuits before anyone can achieve clarity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The story picks up again decades later in Blade Runner 2049 with Ryan Gosling's K, a blade runner who is also a replicant, stumbling on a potentially explosive secret. And ironically, given how completely both films eulogize the possibility of parental bonds, Blade Runner 2049 replicates its predecessor's yearning for them like a rebellious kid, trafficking in fascinating (if ineffective) inversions. These replicants no longer have artificially short lifespans! (Given how huge a plot point this was in this original, this seems oddly unimportant in the sequel.) These replicants can't disobey! (Except they can.)

There's more: Harrison Ford's named protagonist of the first film knows he's not a replicant (but might be), whereas Ryan Gosling's (essentially unnamed) protagonist in this one knows he's a replicant (and might not be). The love interest in Blade Runner turned out to be more biologically human than anyone suspected; the love interest in 2049 lacks a physical body. If the sex scene in Blade Runner was rough and coercive, the sex scene in 2049 demands so much coordination it's almost parodically consensual. The J.F. Sebastian inventor figure in 2049 is a woman, and if the former's space was cluttered and stuffed with inventions and grotesque old toys, hers is totally, radically empty. Both are saddled with strange ailments. Both are child-like. And both can honestly say (to the replicants who come to them for help) that "there's some of me in you."

If 2049 doubles down on its predecessor's epistemological (and cinematic) fog — on the narrative problem of discerning what's real and what isn't — it also sharpens the original's hunger for biological authentication: what rain feels like, the physical basis of memory, what DNA means. People hunger for tangible truths. Cinematographer Roger Deakins and director Denis Villeneuve render this sensory starvation visually: The world's ecosystems have collapsed, and the "blackout" has turned California's farmland white. The world is burned and bleached or wet and black; the palate is therefore a slurry of swimmy oranges and greys, with no blue or green in sight.

The results are achingly beautiful set pieces that are themselves nostalgic. This is a stunning film that somehow makes you homesick for the original. 2049's Las Vegas is magnificent — and so fractured and anxious and elegiac about the past that even the hologram recreations of Elvis keeps blinking in and out. Bees against an orange sky, Ryan Gosling silhouetted against a gigantic high-heeled shoe or a hologram of a ballerina en pointe: These are electrifying images in a movie where even the electricity — that dystopian substitution for substance — keeps going out.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The plot sometimes suffers from the same problem as the electricity. It's … spotty. Gosling's blade runner is a sharp observer ostensibly conversant in detection and surveillance technologies. And yet, several important developments hinge on his being stupid or a complete naif. Jared Leto plays the villain Niander Wallace with an unmotivated creepiness that shocks without quite ripening to an agenda or perspective or point. Sylvia Hoeks does steely work as his assistant Luv, but her characterization is fuzzy: Initially it seems to build into something unexpected and affecting and interesting, but by the end, she's flattened into uncomplicated malice.

That messy plotting — stacked on top of premises that turn out to be rather inconsequential — means that 2049 is (philosophically speaking) pretty diffuse. There are some satisfying parallels — that the civilization-wide "blackout" puns on a loss of memory is just one example — but it's less a thought experiment than a sentimental journey, and the takeaway is something like nostalgia for nostalgia itself. That doesn't make 2049 an unworthy descendant to Blade Runner; in fact, what stands out is how powerfully it insists on its nostalgic kinship with the original, by internally decimating any hope of nostalgic connection. If Blade Runner was an origami unicorn, Blade Runner 2049 is a carved wooden horse: a little less magical, complex, delicate, and weird, but plenty evocative all the same.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

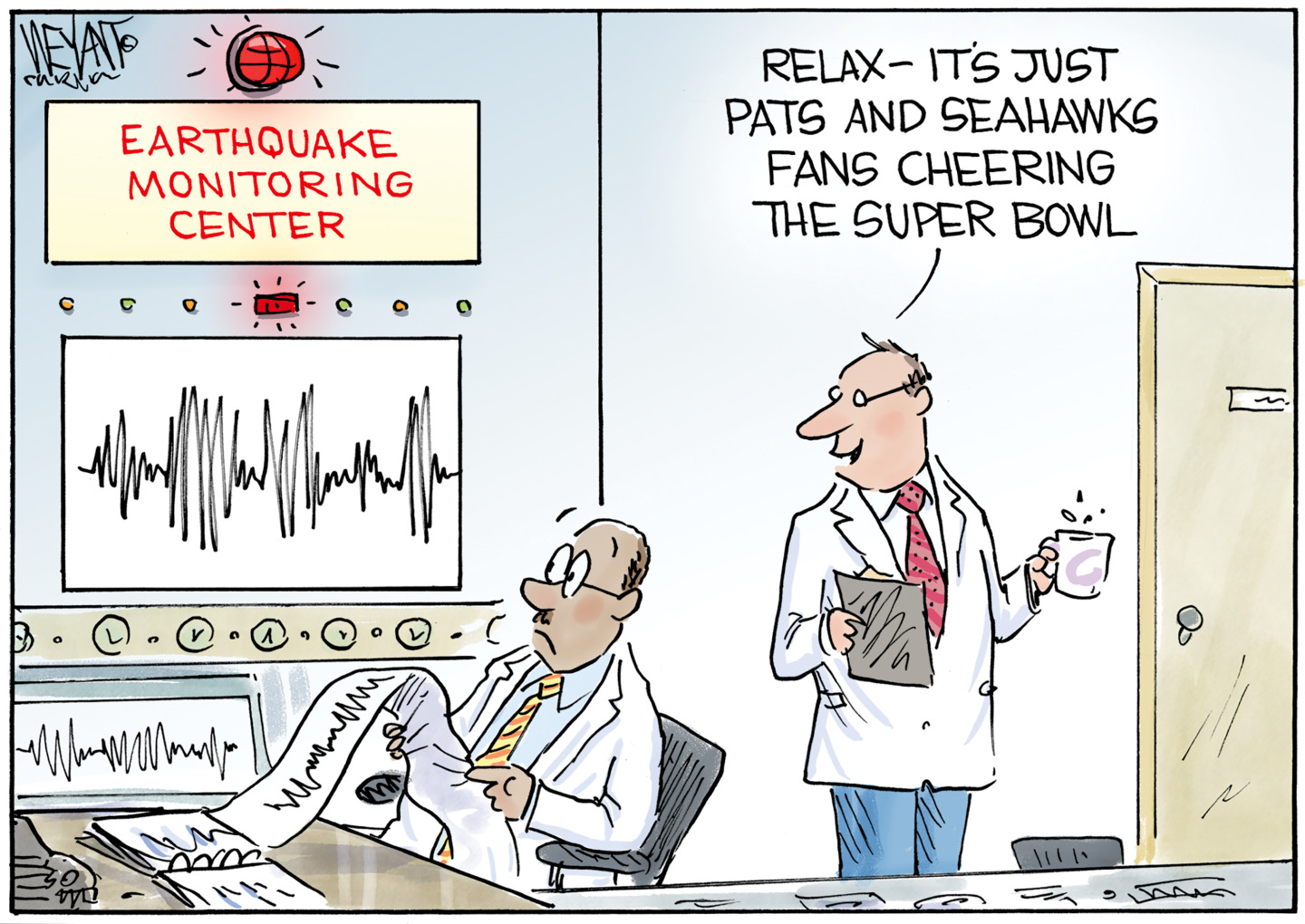

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

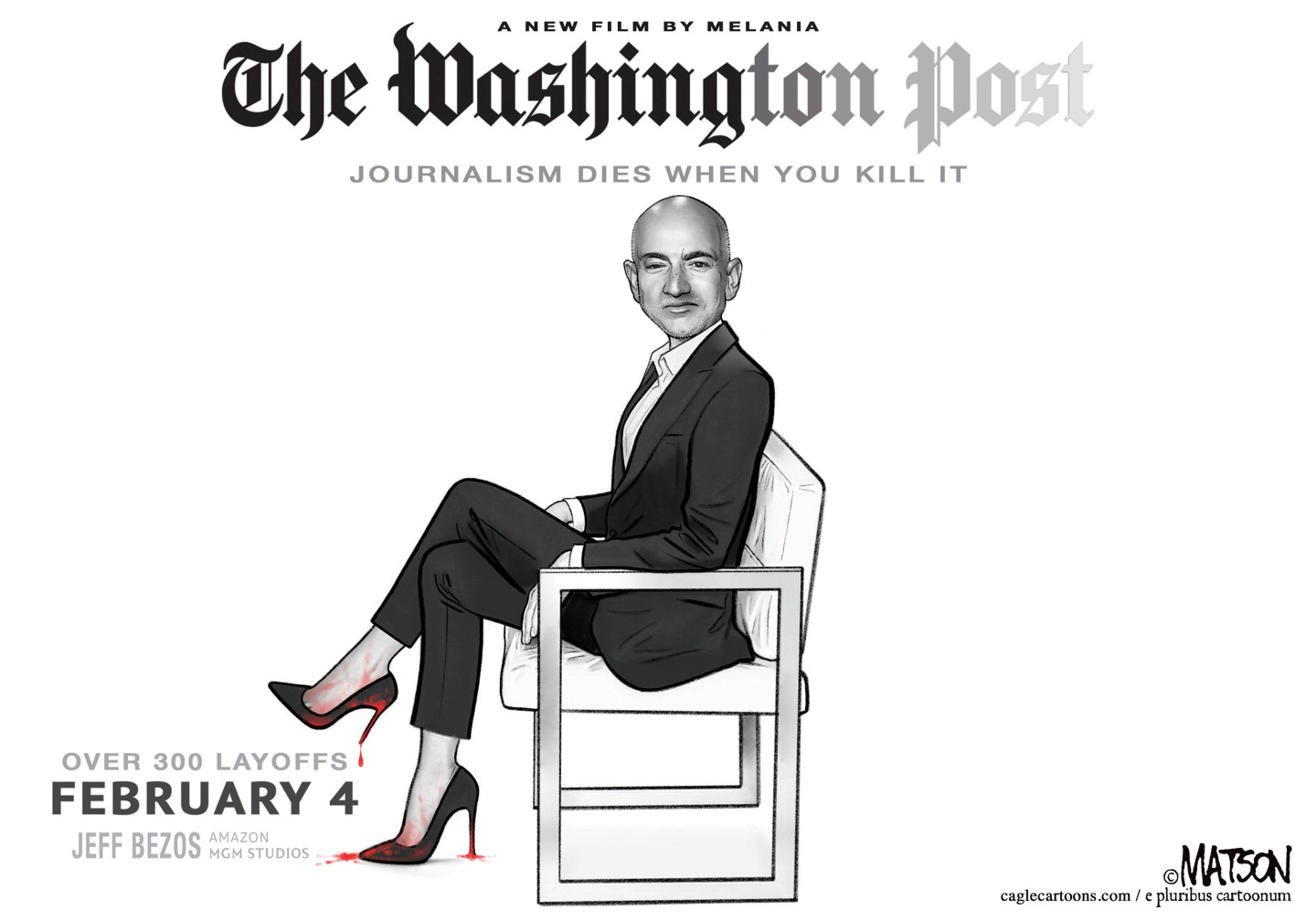

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.