The Evelyn Waugh fanatics

Why the author still has one of the most devoted followings in modern literature

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

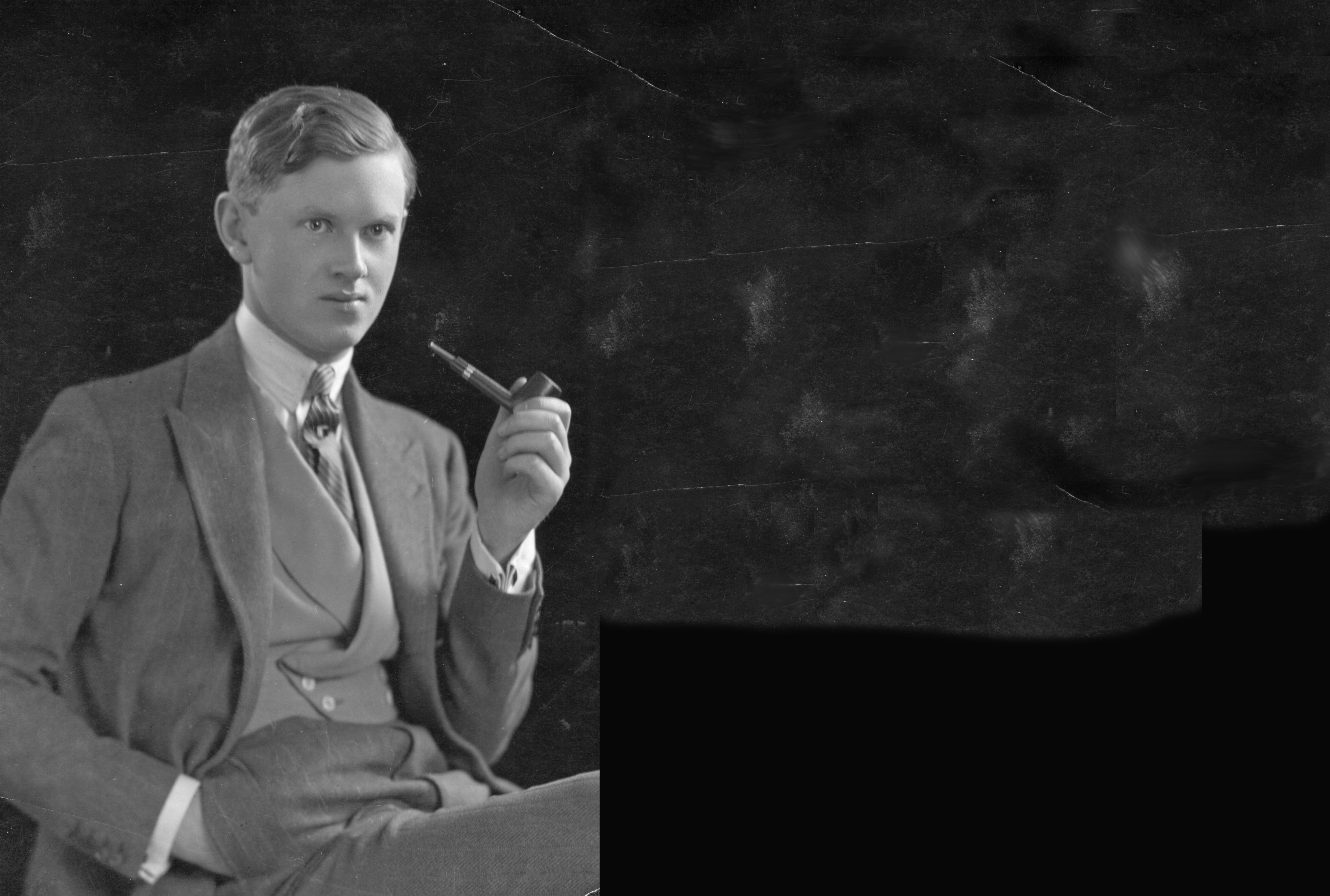

Ninety years ago the English publisher Duckworth issued a biography of Dante Gabriel Rossetti by an unknown writer. The anonymous reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement heaped scorn on the efforts of "Miss Waugh," whom he seems to have regarded as a kind of sexually frustrated maiden aunt.

This was not the last time that Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh would find himself on the receiving end of critical nastiness. Toward the end of his life he was driven to temporary insanity by the questions of BBC interviewers and the hostility of the tabloid press, an experience recounted with bleak hilarity in The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold.

When Waugh died on Easter Sunday in 1966, he was praised by contemporaries such as Graham Greene, who called him "the greatest author of my generation." In death he has been rewarded with one of the most devoted, if not among the most sizable, followings in modern literature. Not one of his novels has ever gone out of print, and even his biographies and travel writings continue to sell tolerably well. Some readers find that Waugh's novels speak to them in an intensely personal manner that is rare among authors working outside of science fiction or fantasy. Decline and Fall, Kingsley Amis said in a retrospective essay, was the "first novel written for me."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I for one can attest to this feeling. Today it is widespread among young men of a certain type, especially in the United States. If you have ever moved in conservative intellectual circles or attended a liberal arts college with a "Great Books" program or gone to the coffee hour at a traditional Latin Mass, you will have seen him (it is almost never a her). The Waughian wears tweed jackets, often if not always ill fitting. He smokes a pipe or one of the expensive additive-free brands of cigarette. He drinks gin and, partly out of spite for craft-beer nerds, Miller Lite. He is a Catholic but has vaguely romantic feelings about English church architecture and says "Holy Ghost" instead of "Holy Spirit." He insists that the Church has been in a crisis since the Second Vatican Council and the introduction of the new liturgy. He rides a bicycle, or at least owns one, and rails against the iniquities of the automobile. He loathes democracy and longs for the restoration of the Stuarts to the English throne. Insofar as he has any opinions about contemporary American politics he loathes the GOP and has a a tendency to romanticize marginal quixotic figures in the Democratic Party — Jimmy Traficant, Bart Stupak, Bernie Sanders. At one time or another he has almost certainly maintained a blog in order to hold forth about most of these things. The Waughian has more than a bit in common with the "young fogey" famously lampooned by Alan Watkins and other English journalists decades ago, except that instead of an Oxford-educated toff he is probably an ordinary middle-class American in his 20s or 30s who discovered most of his causes on the internet.

There is no use in denying that the above paragraph is a partial, and somewhat dated, self-portrait. It would, however, be nearly as accurate if presented as a sketch of dozens of my friends and acquaintances and an untold number of reactionary bloggers, pseudonymous Twitter accounts with handles like "@BurkeanThomist" or "@ChristendomDefender88," Hillsdale and Christendom College undergraduates, and awkward, often slightly overweight unattached young men standing sheepishly in the back pews of Catholic churches on Sundays. I am, I like to think, at least a slightly self-aware Waughian, which is why I am able to recognize that the identification of the author with our set has put many sensible friends of mine — most of them, perhaps unsurprisingly, female — off his work altogether, in much the same way that Janeites who make detailed maps of Pemberley and hold tea parties on the great lady's birthday have led some men to ignore Jane Austen. In both cases this neglect is unfortunate, however understandable. But the author of Pride and Prejudice at least enjoys the authentic Leavisite imprimatur; she is not merely a Penguin Classic but the genuine article, her novels edited by the world's most esteemed English textual critics and made the subject of thousands of scholarly articles each year.

Oxford University Press last year began issuing Waugh's Complete Works in an edition projected to run to some 42 volumes. This massive scholarly undertaking is the result of many years of work by Waugh's grandson, Alexander, and a team of experts who are carefully sifting through the manuscripts at the University of Texas, Austin, and the massive correspondence, no more than 15 percent of which has been published in the three extant collections of Waugh's letters. As scholarship the new editions cannot be faulted. Flipping through the Rossetti biography again for the hundredth time since October I find that I am filled with delight by the random, glorious accumulation of details (the original advertisement for the book that appeared in the TLS clearly identifying its author as male, for instance). No modern novelist outside the experimental milieu of Joyce and Faulkner has ever received such careful and sustained attention from scholars. How far can we be, I wonder, from the Oxford Wodehouse or the Yale Complete Prose Works of John le Carré?

Somehow, though, it all seems a bit soon. There is something to be said for the pleasure of reading books with no sense of obligation rather than as set texts. (This is why our childhood favorites exercise an odd fascination even after we recognize that Star Wars Junior Jedi Knights: The Golden Globe is not among the highpoints of post-war American literature.) The idea that instead of being harmlessly enjoyed by dorks in three-piece suits Scoop might be the sort of thing high-school sophomores get the SparkNotes for fills me with low-level dread. The best way to ruin a writer is to make him important or, even worse, essential.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Will the American fandom survive Waugh's classic status? I hope so. Of all the goofy youth subcultures — Tolkien appreciation, with which it sometimes overlaps, or going Goth — it is easily the most harmless. Speaking from painfully confessed experience I think there is something wholesome about the whole shtick, even if it is just the pseudo-highbrow equivalent of going to the mall to laugh at the plastics. Dressing up in a thrift-store parody of '20s clothes and fussing about bad vestments and the decline of English prose is not for everyone, of course, but neither is otter erotica.

Which is why I cannot quite be sanguine about the new Oxford Waughs, no matter how much pleasure they will afford some of us in the short term, despite their $100-a-pop pricetags. Like the Janeites before us, Waughians might well be able to carry on uneasily in the same world as the bored college students and the disinterested scholar-critics. But somehow I fear it will not be possible for us to appreciate our man in quite the same way ever again.

Thus does that vague enemy, the modern world, claim another casualty.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.