The last American prophet

Remembering Tom Wolfe

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

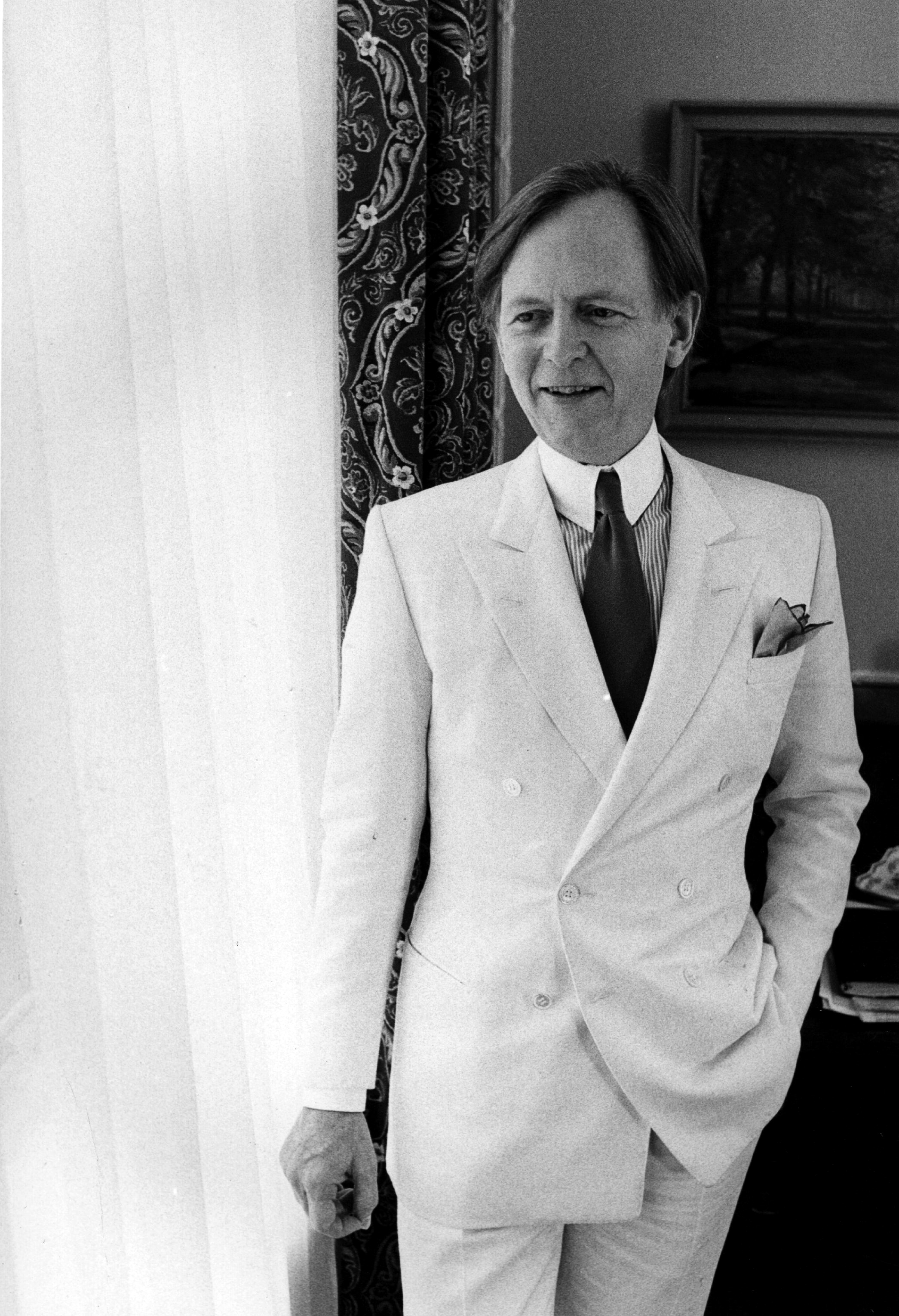

Tom Wolfe, who died Tuesday at the age of 88, was the last American prophet. He seemed to know it, too, if the white suit is any indication.

For six decades he chronicled the United States of America with his steady eye for detail and rich diction. Twain captured his era in his fiction, Mencken in his journalism. Wolfe did both, often at the same time. But he went a step further than his literary forbears. He not only diagnosed correctly what was happening in America, but predicted where we were heading.

Wolfe trained his eye on the evolution of status and social rank in America. He could see the direction of the nation and its elites because he recognized what Americans were striving for; there was no need for abstraction when you could see an individual goal. The self-fulfillment of the '70s, the greed of the '80s, the fame-seeking of the '90s, the confusion of the aughts, and group identity of the teens — Wolfe predicted it all years before it happened. Neo-liberalism? He saw it coming in Radical Chic (1970). Al Sharpton? Bonfire of the Vanities (1987). Hidden-camera gotcha journalism? Ambush at Fort Bragg (1997). #BlackLivesMatter and the white supremacists brandishing torches at Charlottesville? Back to Blood (2012). Even Wolfe's literary mistakes have proved prescient. A Man in Full (1998) may be overwrought and overcomplicated, but it did illustrate post-NAFTA America. I am Charlotte Simmons (2004) was agonizing at times as Wolfe attempted to use the vernacular of a young millennial woman, but there is no better illustration of a 21st century journalist nor female disquiet over their inheritance from the sexual revolution.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Wolfe overwrote to the point where one could be forgiven for assuming the length justified the relative slow pace at which he labored. One is even tempted to assume he did not want to see one ounce of reporting go to waste. His deft craftsmanship and humor overcame the trivial nature of the details — think of his description of Bonfire's Assistant District Attorney Larry Kramer's "massive sternocleidomastoid muscles," that is, his neck, and the lengths to which he went to flex them to illustrate Kramer's self-consciousness at his lack of Irish toughness. Even seemingly inconsequential details are infused with meaning, and each one contributes to the portrait of his characters. This knack for the trivial has been perverted by his heirs in longform journalism where detail for detail's sake is used as a signaling device from writers eager to show that they are longform journalists — try reading a profile that does not contain an exhaustive description of kale salad or salmon these days.

Wolfe did have his weak spots. His verbal gymnastics became his signature even before he adopted the look of the Southern Dandy. He may have shunned the first person style that some of his fellow New Journalists used as a crutch, but his wordplay, affected vernacular, and Batman-esque onomatopoeia could — WHAM — distract as much as any Hunter S. Thompson exaggeration ever did. At times it reeked of the desperation that tempts all writers, the idea that readers should KNOW they are reading a Tom Wolfe piece.

What distinguished Wolfe from his counterparts in New Journalism was his ability to turn a phrase that stuck. Thompson came to embody the greatest excess of the 1960s with his narcotic inventory just outside of Barstow, but Wolfe's labels and diagnoses became clichés, they so accurately captured the time at which he was writing. The Thompson that shot himself in 2005 was the same Thompson that got jumped by the Hells Angels in 1967 and skewered Nixon in 1973 as if suspended in perpetual literary adolescence. But Wolfe stamped the era: from the "Right Stuff" to "Radical Chic" to the "Me Generation" on down to "social X-rays" and "Masters of the Universe."

It is difficult to call a man who received a $7 million advance on his last novel underappreciated, but it's true. Thompson appears on college curriculums; Johnny Depp and Bill Murray play him in movies; his self-involved cover letter goes viral; so does his doubtlessly invented daily schedule. There's an advantage to forever affecting the hippie rebel identity, especially when the hippie rebels wrest power from the WASP order they rebelled against. Meanwhile, Wolfe spoke truth to power, afflicted the comfortable, and whatever other cliché journalists plaster onto their Twitter profiles until the day he died. He mocked old money heiresses and their rebel pretenses, new money Wall Street and its arrogance, academia and its status-obsessed meritocracy. He mocked Darwin and Chomsky, for Darwin and Chomsky's sake!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Wolfe returned to nonfiction for his last book. The Kingdom of Speech didn't poke holes in natural evolution, so much as laugh at it and the blind faith elites use to prop it up, knowing that the average Darwin defender has never cracked the cover of The Origin of Species. He saw the Idol of Intellectual Respectability resting on a Corinthian column and gave the column a good shove. Saint John Paul the Great couldn't bring himself to question Darwin's "bow wow" theory on the origins of human speech, but agnostic Tom Wolfe did.

Wolfe's ability to see the consequences of America's habits reflected his deep reporting into the lives of his characters. He did not satisfy himself with the spectacle of his subjects, but delved into their goals to discern their motivations. Therein lies the difference between Wolfe and his heirs in both of his professions; narrative did not interest him so much as end-game. Show him what you value and he'd show you where you'll end up.

Bill McMorris is a staff writer for the Washington Free Beacon. His work has appeared at CNN, Fox News, The Economist, The Colbert Report, Wall Street Journal, and The Federalist. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia with his wife and three daughters, probably four when the next baby comes in July.