The internet sales tax is going to pummel small businesses

Thanks to the Supreme Court, online mom-and-pops are in for a rough ride

What do you do when making taxes fairer also means making them harder on the little guy?

On Thursday, the Supreme Court overturned decades of law and precedent by allowing states to levy sales taxes on internet purchases. Like many things in life, the South Dakota v. Wayfair decision is a mixed bag. On the whole it was probably the right call, cleaning up an enormously incoherent and unfair tax regime that's only gotten worse as online retail has expanded.

But it will also hit many small businesses hard. "For us, an internet sales tax would mean the certain end of our business," one family-owned trading card shop wrote in USA Today.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To tease all this out, we need to go back to 1967, when the Supreme Court first set what was known as the "physical presence" standard in its Bellas Hess decision. The idea was that states and localities could only tax a sale if the business conducting it had some kind of brick-and-mortar establishment within their borders. Back then, this applied to almost all transactions, so it wasn't a big deal.

The Court revisited the issue in 1992 with the Quill ruling. By then, the growth of mail order catalogs was raising the question of sales where the customer certainly has a physical presence in a state or municipality, but the business does not. Still, it was a minor enough problem that the Court reaffirmed its prior ruling. A few years later, in 1998, Congress effectively codified the Court's "physical presence" standard into law.

Then the internet happened.

Today, almost 10 percent of all retail is conducted online, potentially falling into the conceptual lacuna of the "physical presence" standard. The total number of taxing jurisdictions has exploded from 2,300 in 1967 to 12,000 today, 45 states have sales taxes of some sort, and thousands of local governments do as well. No one knows how much tax revenue is collectively lost from internet sales every year, but estimates range from $8 billion annually to as much as $40 billion. State governments in particular are feeling the pressure, as more and more of their budgets are eaten up by health care and education costs, forcing cuts to other necessary services — a conundrum that could be alleviated by the extra sales tax revenue.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Each year the physical presence rule becomes further removed from economic reality and results in significant revenue losses to the States," Justice Anthony Kennedy writes for the majority. "These critiques underscore that the physical presence rule, both as first formulated and as applied today, is an incorrect interpretation of the Commerce Clause."

Congress of course knew about the problem for years, but dragged its feet on revising the 1998 law. Thirty-one states responded by pushing the envelop with laws taxing internet sales. Eventually South Dakota just forced the issue by suing several online retailers to start collecting sales taxes, leading to Thursday's decision.

Here's where things get interesting. Nineteen of the 20 largest online retailers, including Apple, Target, Macy's, and Walmart, already collect sales taxes from all their customers who buy online. Some of this is practical: Even internet sales require some physical infrastructure like warehouses, so the biggest companies actually meet the physical presence standard in a growing number of states and cities. But some of it is just a political consideration. And as a result, some major online retailers — like Overstock, Newegg, and Wayfair — still don't collect sales taxes. Obviously, this gives the latter companies an arbitrary competitive advantage against the former group.

Amazon is also an interesting complication here. The online behemoth sells a lot of its own stock to consumers, and already applies sales taxes to all those transactions. But it also serves as an online platform for many third-party vendors, who often don't collect sales taxes. This is as much as half of Amazon's business. The lack of a sales tax on those transactions helps Amazon, and it obviously helps the smaller online businesses working with Amazon.

South Dakota v. Wayfair didn't just pit states against online retailers, it pitted some large online retailers against others. And it pitted the large online retailers who do collect sales taxes against the smaller business who don't.

The new decision doesn't just mean all those small businesses with online sales will now lose more revenue to taxes. It means they'll also have to spend money on systems that can keep track of their various tax obligations. That's 45 states, each with its own particular sales tax law with different rates and quirks, not to mention many, many more city and local government sales taxes. Obviously, in the digital age, software can take care of much of the hassle. But according to testimony in the case, those systems can still cost as much as $200,000 to set up. All those additional costs could drive a lot of small businesses under.

On the flip side, there are a lot of brick-and-mortar small businesses who don't have an online presence.

Meanwhile, one-third of all American consumers live in states that have significantly streamlined their tax collection systems to deal with the internet age, including South Dakota. Indeed, the Supreme Court explicitly noted South Dakota's system in its decision, suggesting it might frown at states with more burdensome tax setups in the future. Twenty-four states have already agreed to offer free software to help businesses sift through sales tax obligations, so you could see the South Dakota v. Wayfair decision force the remaining states to up their game.

Voters and politicians place a big emphasis on helping and preserving small businesses. But there are good ways to go about it and not so good ways. One example of a good way would be to aggressively enforce antitrust law to break up major market players. But the government has whiffed on that for decades. A bad way would be to exempt small businesses from all sorts of regulations like labor rights law — something that happens quite often.

Providing some small businesses with what Justice Neil Gorsuch referred to as "a judicially created tax shelter" seems to fall into the second group. Small businesses may be the little guys, but they're not as little as the ordinary citizens who need well-funded public services.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

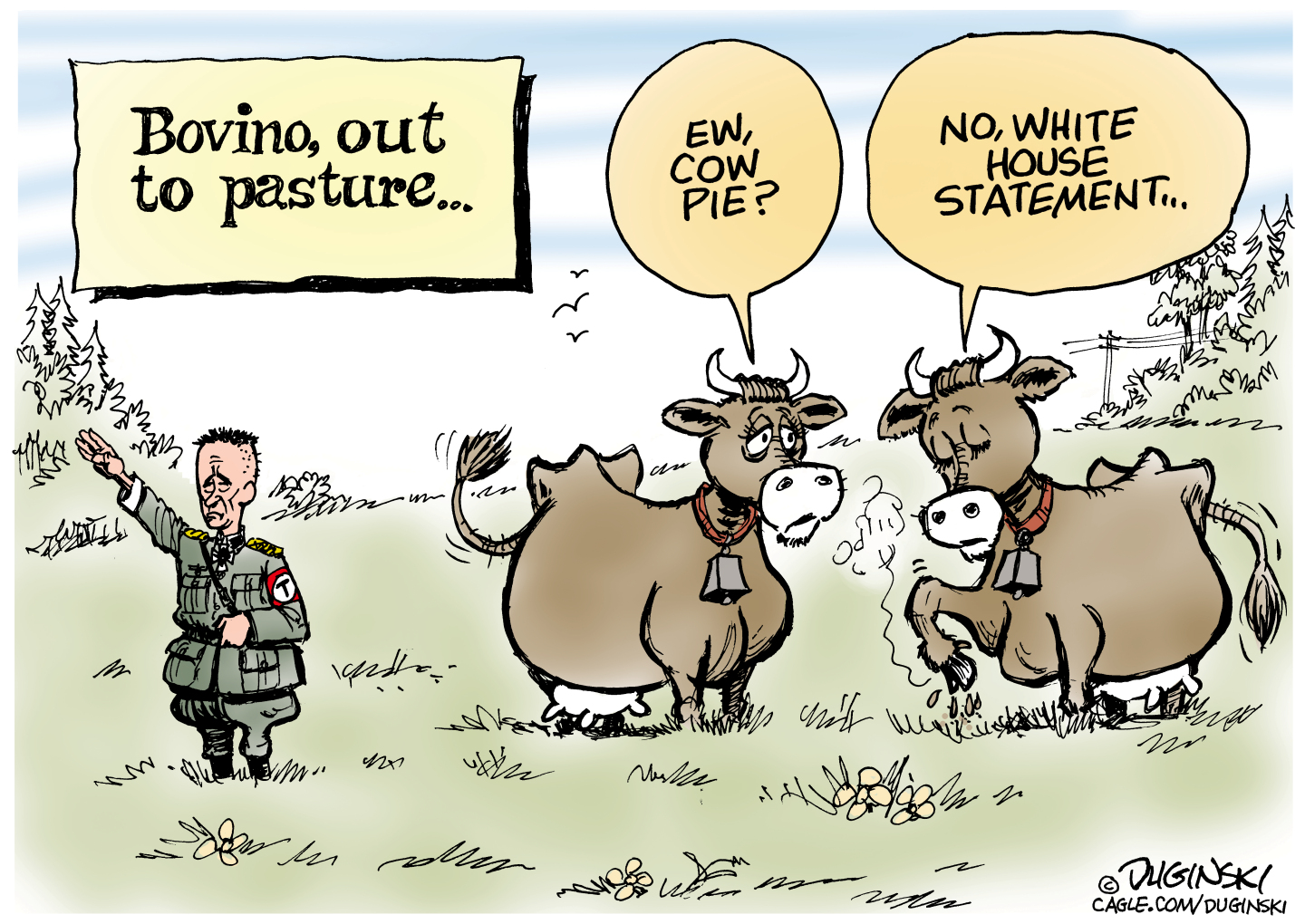

5 redundant cartoons about Greg Bovino's walking papers

5 redundant cartoons about Greg Bovino's walking papersCartoons Artists take on Bovino versus bovine, a new job description, and more

-

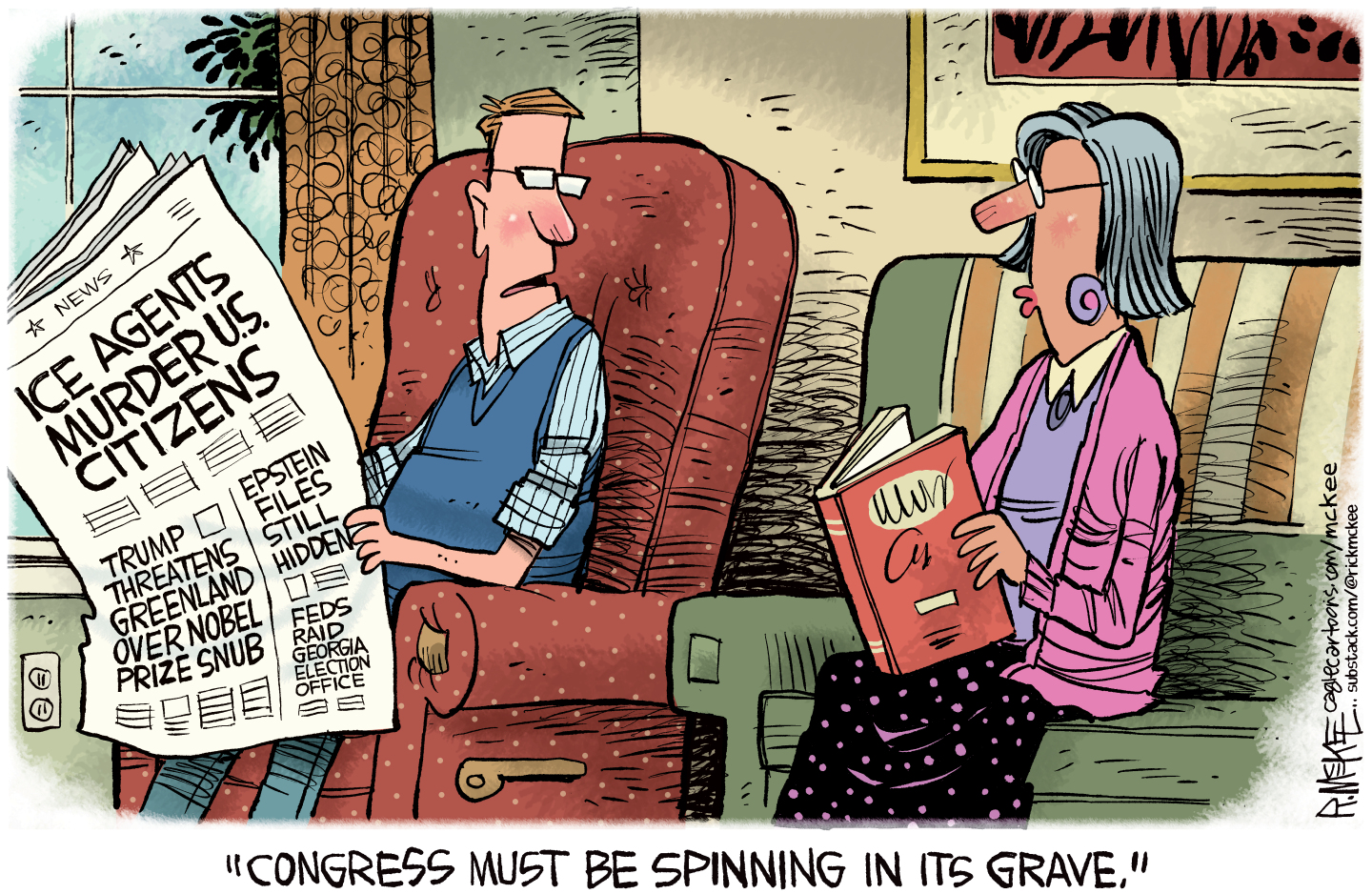

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more