Google is not an American company

It is nothing and nowhere and endless — and frankly, un-American

Unless President Trump has finally adopted the royal first-person plural and owns a significant amount of Google stock, it is hard to know what the president meant when he complained on Thursday that the European Union has slapped a $5 billion fine on "one of our great companies."

Because whatever else it may be, Google is not an American company.

"Google" is, more than anything else, a logo and a marketing label; it is also a subsidiary of a holding company called XXVI, which is in turn a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc., a corporation that is also an umbrella for a number of other venture capital and research entities. For another two years, until the deadline imposed by an Irish court expires in 2020, Google or Alphabet or the Money Machine or whatever you want to call it will continue to steal from the rest of us by means of two accounting schemes known as the "Irish Double" and the "Dutch Sandwich."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A rehearsal of the specifics of these arrangements would exhaust the space of a column, but what they mean in practice is that Google has an Irish subsidiary that swallows up billions in revenue, which is then moved to a Dutch company — one which employs exactly zero persons — before being passed on to another outfit based in the Bahamas but also registered in Ireland. This labyrinthine scheme allows it to avoid paying billions of dollars in taxes on the advertising revenue it generates when people in countries around the world use its ubiquitous search engine on their smartphones, tablet devices, and computers. Estimates suggest that this strategy has left the tech giant with an effective tax rate of less then 20 percent, 15 percent lower than the longstanding U.S. rate of 35 percent. (The GOP's tax reform bill slashed the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent beginning this year.)

These tax schemes have been immensely profitable for Google. Just last year it was able to avoid paying more than a billion euros in France because a court ruled that it had no meaningful presence in that country. Which is true, I suppose. That's the whole point: Google isn't liable because it is nothing and nowhere and endless.

Nice work if you can get it. An ordinary American running a business or earning wages who makes $40,000 a year can't say that, actually, the labor he or she performs on behalf of his employer isn't subject to taxation in a particular place and thus save himself a few grand a year at tax time. Only the poorest and the richest Americans avoid paying taxes, the former because they don't make enough money, the latter precisely because they make too much.

It is disgraceful. The tax dodging that has allowed Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and other tech companies to become the largest and most profitable in the world — while the corporate bogeymen of yesteryear, such as Walmart, for all their faults at least put something back into the system that makes their ill-gotten gains possible — is theft on an almost indescribably massive scale. When Trump tweeted that the European Union was "taking advantage" of the United States by fining Google over an antitrust violation involving Android, he was getting things exactly backwards. It is actually Google that is taking advantage not only of us but of the European Union and people the whole world round.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When I say that Google is not an American company, I don't just mean that practically speaking it manages to avoid some of the most straightforward consequences of being one — namely, having to pay taxes at current rates. I also mean that, by extension, Google is un-American. It has no stake in the American people or their flourishing or even their basic well-being. This is not to say that Google cares overmuch about the flourishing of people in other parts of the world either. Some 23 percent of Bermudans live in poverty.

Google, with its ability to generate unimaginable amounts of income without producing any tangible product or benefiting, even indirectly, anyone who is not involved in it is virtually unprecedented in history. It represents something new in human affairs, so new, in fact, that we cannot hope to describe it unless we resort to the language of biology. "All that is solid melts into air," Marx wrote. After the ice caps of community and tradition have melted in the technogenic heat of globalized capital, new flora and fauna appear, evolved to flourish under the new conditions. Google is such a specimen, indeed a perfect one, a kind of incorporeal fungus that aborbs nutrients without leaving a trace or even wrapping its tendrils around its host.

Donald Trump was elected president in 2016 not because he made a secret deal with Vladimir Putin that involved tricking union retirees into clicking on Facebook bots but because, like Bernie Sanders, he spoke to the anxieties of millions of Americans who felt that the institutions — public and private alike — that dominate the modern world cared nothing about them. But speaking is not the same thing as understanding or feeling or even believing, much less doing. The idea that the EU's recent attempt to limit the ability of a parasite like Google to suck obscene amounts of revenue out of Europe was an attack on this country or her people shows us that he knows nothing of globalization and its discontents.

This is unsurprising. The president is lashing out at the EU because the other day he ran his mouth and called Europe a "foe" of this country. He would have seized on any example at hand in an attempt to justify his latest assault on common sense. If he knew what he was talking about, he would have reserved his disapprobation for a real enemy of the United States — Google, for example.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

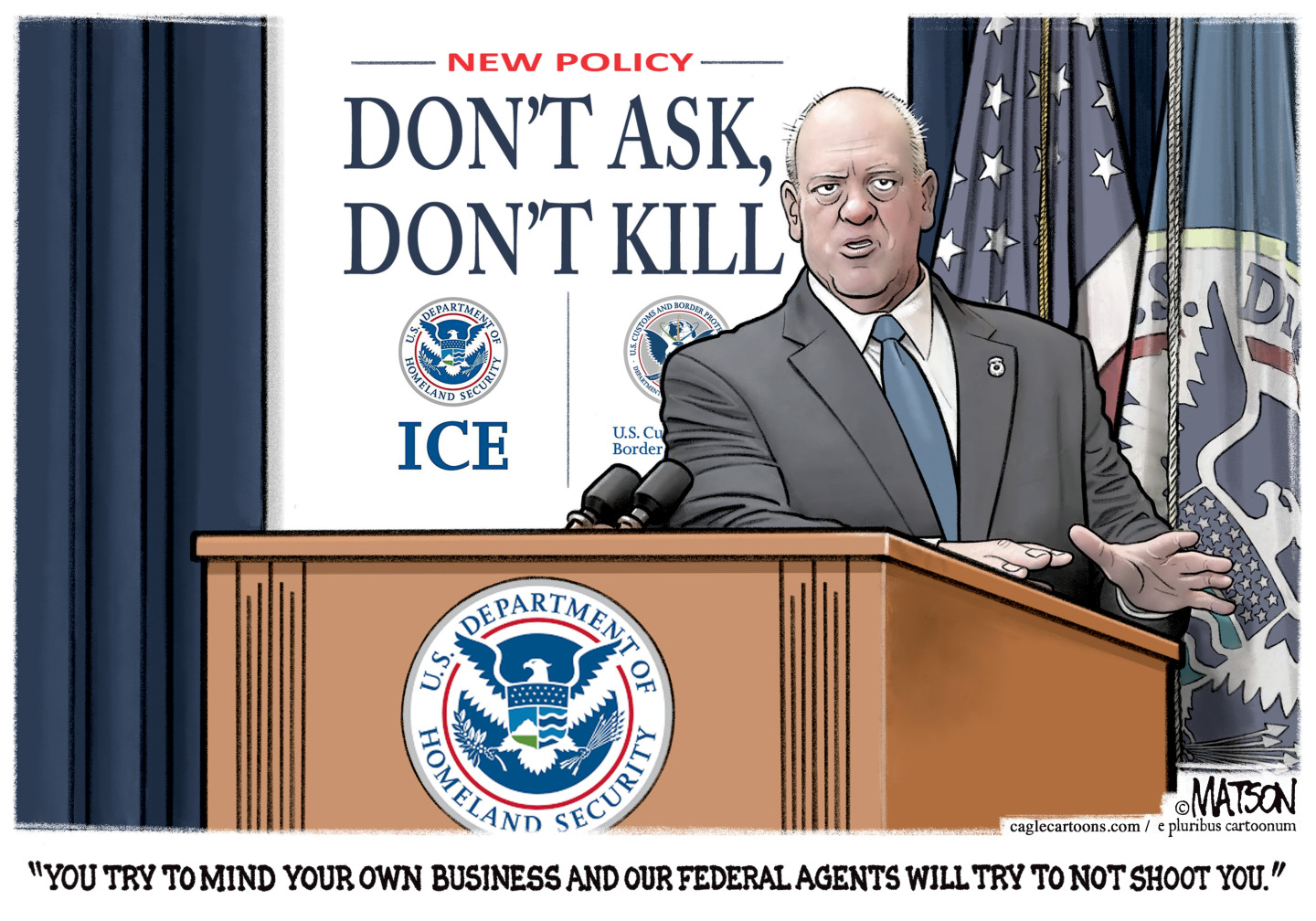

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more