What's a yield curve inversion and why is everyone freaking out?

Does is it really mean a recession is imminent?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sound the alarms, man the battlements, and gird your loins for the next recession. The yield curve has inverted.

Anxious headlines blared the news across the financial media. The U.S. dollar dropped on Tuesday, spooked by recession fears, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged a stomach-turning 800 points — making Tuesday one of the stock market's worst days of 2018. "Bond king" and Doubleline CEO Jeffrey Gundlach declared that the "economy is poised to weaken."

Okay, you're probably wondering, what in God's name is the yield curve? For that matter, what do you mean it "inverted?" Who cares? What does any of this have to do with a recession?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Glad you asked.

It's actually simpler than it sounds. The yield is just the return on investment someone gets from buying a bond. The yield curve is just the difference between yields on two different bonds that have the same quality, but different maturity dates. Yields on 10-year Treasury bonds minus yields on 2-year Treasury bonds is a particularly common example. (It's called a yield "curve" because of how the relationship is sometimes presented in financial analysis.)

You can technically get a yield curve from any sort of bond. There are tons to choose from. But the market for U.S. Treasuries is the biggest and most influential bond market in the world, so usually when people talk about a yield curve they're talking about Treasury bonds. Even then, they could be talking about 10-year minus 2-year Treasuries, 5-year minus 3-year, 5-year minus 2-year, etc. The Federal Reserve's data website is quite handy for anyone who really wants to geek out: With a few minutes of work, you can pick out whichever two bonds you like, chart the difference, and examine it over time.

Now, what about this "inverted yield curve" that has markets in a panic?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Usually, yields on long-term bonds are higher than yields on short-term bonds. In that case, the difference between the two is positive. But every so often, short-term yields will overtake long-term yields, which produces a negative spread. That's when the yield curve "inverts."

The reason everyone got excited was that the difference between 5-year and 2-year Treasuries and between 5-year and 3-year Treasuries both went negative on Monday. It was the first time either had inverted since 2007.

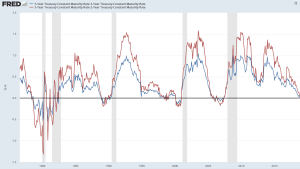

And if you look at the behavior of both spreads over time, you'll probably notice why this made everyone nervous.

(Courtesy of the Federal Reserve)

Every time the spreads have gone negative (fallen below the thick black line in the graph) a recession (the light gray areas) has followed soon thereafter. That's true of both those spreads, and of the much more closely-watched 10-year versus 2-year spread. It's also true of the 10-year versus 1-year spread, which has gone negative before every recession since at least 1957. It really is kind of like clockwork. On top of that, there are basically no false positives.

All that makes yield curve inversions an unusually reliable indicator of coming downturns. "Any inversion of any sort is a surefire sign of a recession," Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told the Wall Street Journal in July.

The good news, to an extent, is that inversions are also a very early warning system. Most leading indicators of recessions show up six months to a year before the downturn hits. Yield curve inversions give you at minimum one year's notice, and often as much as two or more. One time in the 1960s, the 10-year minus 1-year spread went negative for almost three years before the next recession. And neither the 10-year minus 2-year spread or the 10-year minus 1-year spread have even gone negative yet.

Put it all together, and — assuming the trend continues — we won't see a recession until late 2020, give or take a few months.

Now, keep in mind, yield curve inversions don't cause recessions. How the yields on various Treasury bonds behave over time is a mixture of Fed monetary policy decisions, plus the buying and selling decisions of millions of individual investors. The Fed could try to tweak short-term and long-term interest rates to hold off yield curve inversions, but the central bank is ultimately boxed in by its obligations to both maximize employment and prevent runaway inflation. Meanwhile, investors in the bond market are just trying to anticipate how the Fed will respond to economic conditions and then how conditions will respond to the Fed.

Think of the yield curve as a distillation of the crowd wisdom of millions of investors all trying to predict the future. If the yield curve inverts, it means the crowd wisdom anticipates a big drop in interest rates sometime in the next year or two, for whatever reason. And big interest rate drops usually mean recessions.

Of course, yield curve inversions could always fail as an indicator as well.

Accurately predicting every recession since the midcentury seems a pretty impressive record. But it's not that long a time frame in the grand scheme of things. It's entirely possible that structural forces and balances in the economy could someday shift in a way that renders the yield curve a much less useful predictor.

The Great Recession certainly shook things up. For instance, the Fed and other central banks own many more long-term bonds than they used to, which is holding down long-term rates. Investors have also changed their expectations for returns from bonds with longer maturities, which also affects the spread and its effectiveness as a bellwether. Most likely, neither of those things have rendered the yield curve useless. But they could increase the lag time between an inversion and the arrival of a downturn.

As economist Jared Bernstein put it, we'll never be able to predict recessions with total accuracy. What we should do is make sure our policy setups are ready to counteract the crisis whenever it arrives.

That, more than anything, is what Monday's news should spur us to do. We've still got time.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy