The forensic pathologist who shed light on police violence

Forensic pathologist Bennet Omalu shook the NFL with his findings about traumatic brain injury. Now he's upending California law enforcement with his findings about police violence.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in San Francisco magazine. Reprinted with permission.

Bennet Omalu is not a man who seeks out controversy. He's been known to flee it, in fact. But it has a way of finding him.

Last March, 22-year-old Stephon Clark became the latest flash point in the ongoing national furor over the police use of force against African-Americans. After the unarmed black man was shot and killed by Sacramento police officers in the backyard of his grandmother's house, Black Lives Matter activists led a march that shut down Interstate 5 and forced the cancellation of a Sacramento Kings NBA game. A week after the shooting, during a game between the Kings and the Boston Celtics, both teams wore jerseys with Clark's name and the words "Accountability" and "We Are One" on them during warm-ups and the playing of the national anthem.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

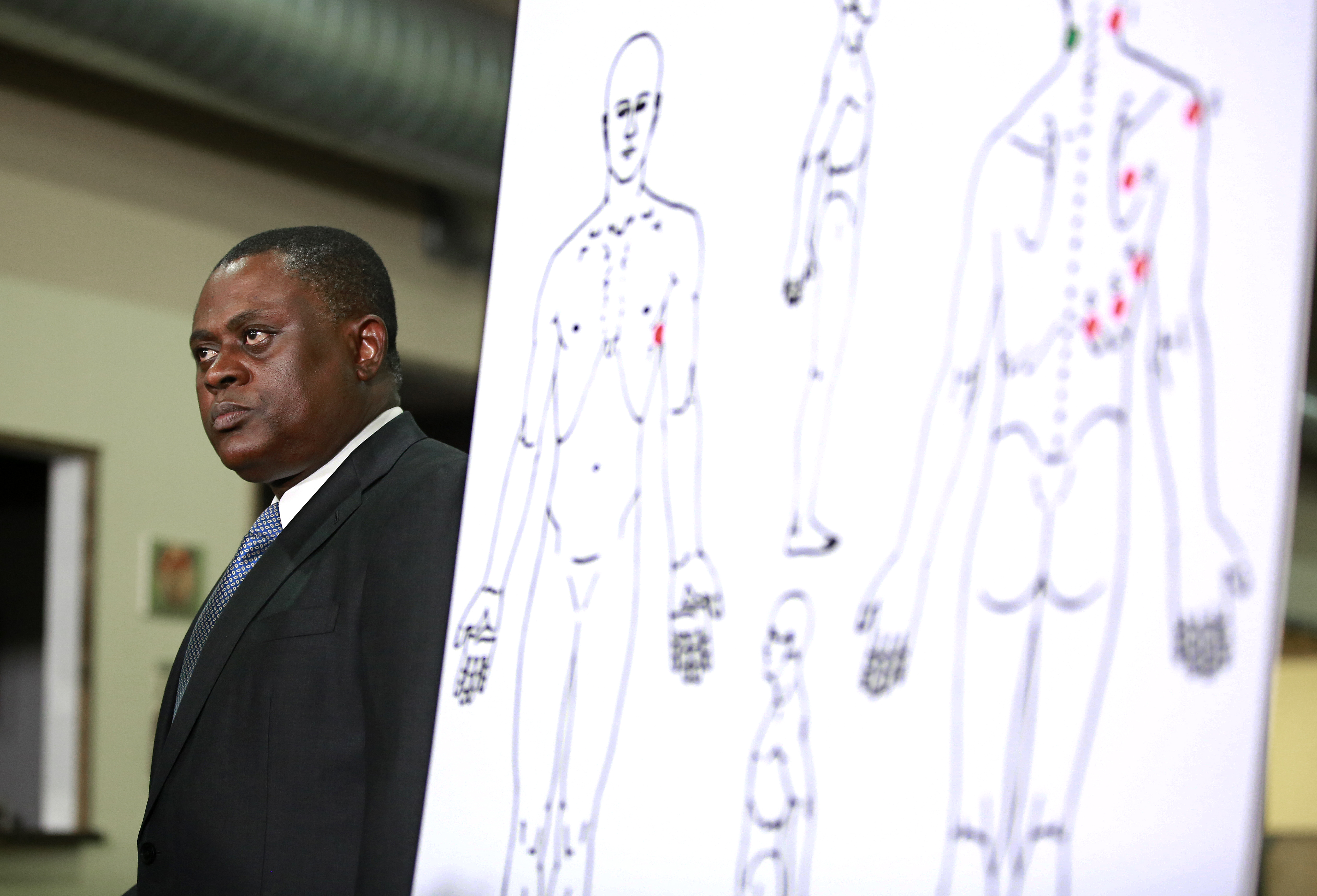

Soon after Clark's death, his family contacted Omalu, a forensic pathologist, and asked him to perform a private autopsy. On March 30, Omalu released his findings. He determined that Clark had been shot eight times and that six of the bullets had entered the back of his body. This cast doubt on the veracity of the police report, which stated that Clark had been approaching the officers when they fired. In response to what the county coroner called the "erroneous information" provided by Omalu, the following day the county released its official autopsy, which found that Clark had been shot seven times, only three times in the back.

A soft-spoken, devoutly Catholic, 50-year-old forensic pathologist from Nigeria is not exactly the first person you'd expect to keep materializing at the center of major American controversies involving contested deaths and charges of official cover-ups. Yet Omalu has now played a leading role in three such scandals — including the mother of all sports-medicine train wrecks, the National Football League concussion debacle.

For a man who became a forensic pathologist in part because, he says, it "placed me as far away as possible from living, breathing patients while still allowing me to practice medicine," Omalu has had a career — and a life — crowded with high-pressure human interaction. He grew up in a village in southern Nigeria during the Biafran War; his family was displaced, and his father was almost killed at a checkpoint manned by militiamen hostile to his Igbo tribe. He earned his medical degree but suffered from depression and desperately wanted to get out of corruption-riddled Nigeria, where he once watched a patient die in a hospital because the surgeon on duty inexplicably refused to operate. In 1994, Omalu managed to obtain a coveted visa and immigrated to the United States to study cancer epidemiology at the University of Washington.

Omalu venerated the United States as a place that "sets you free to be whatever you want to be," but in Seattle he learned about its darker side: Employees followed him in the grocery store, and police repeatedly stopped him as he walked through his mostly white neighborhood. Omalu didn't understand what was going on — "I thought there was something wrong with me," he says — until his landlady suggested that he go to the library and read up on U.S. history. "Slavery, ah! Civil rights, ah!" Omalu says.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After Seattle, Omalu did a residency in clinical and anatomical pathology at Columbia University, then completed several fellowships and earned master's degrees in public health and business administration at other universities. His curriculum vitae runs to 32 pages. He was determined that his skin color would not hold him back, and he regarded education as the key. "I may have overcompensated," he jokes.

Omalu produced his forensic masterpiece in 2002, as an unknown pathologist in the coroner's office in Allegheny County, Pa. One day, he was assigned to perform an autopsy on the brain of former Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster, and he discovered that it was riddled with lesions — the first diagnosed case in an NFL player of what he would come to call chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Additional research confirmed his hypothesis: The repeated blows to the head suffered by most football players put them at risk for serious brain damage.

During a long and tortuous process that culminated in a class-action lawsuit brought by 20,000 former NFL players — and the league finally admitting that there was a link between football and CTE and creating a $765 million fund to help deal with the problem — Omalu became a hot commodity. Journalists sought him out for quotes, and job offers came in from all over the country. But there were just as many negatives: Strange cars began following him; other scientists took credit for his discovery. Battered and overwhelmed, Omalu fell into a deep depression. I wish I had never met Mike Webster, he told himself.

At this moment, an unlikely escape hatch opened: Out in California, an official at San Joaquin General Hospital began wooing him to be the county's chief forensic pathologist. Omalu and his Kenyan-born wife, Prema, were flown out and given tours of San Francisco, Sacramento, and Napa Valley. Worried about her husband's depression and smitten with the idea of a move west, Prema urged Omalu to take the job. He did, and in 2007 they moved with their son to Lodi, a midsize city north of Stockton that is surrounded by farmland. It felt like the middle of nowhere, which was just what they were looking for. He and his family soon fell in love with San Joaquin County.

"Lower profile, no NFL presence," Omalu says, "I just wanted out. A lot of people think I want attention. I don't. I was running away from it." He didn't realize he was about to find himself involved in another high-profile controversy.

Omalu's new boss was the sheriff of San Joaquin County, a bow tie–wearing department veteran named Steve Moore. The system Omalu would be working in, called a sheriff-coroner system, is highly unusual. In Pennsylvania, Omalu had worked within the far more common medical examiner system, in which physicians, often board certified in forensic pathology, declare the manner of death. Only in California, South Dakota, Montana, and Nevada can the person who makes that determination also be the county's top law enforcement officer.

In a sheriff-coroner system, a forensic pathologist like Omalu is responsible only for determining the medical cause of death, such as asphyxiation or blunt force trauma. The far more legally consequential manner of death — accident, homicide, or suicide — is ruled on by the sheriff, although the medical official also issues a recommendation. The potential conflict of interest is obvious: When a person dies in police custody, should the sheriff be the one investigating the death?

Omalu's first major problem with Moore began in the summer of 2008, after the body of Daniel Lee Humphreys was wheeled into the morgue. The 47-year-old had crashed his motorcycle on Interstate 5 while fleeing from a California Highway Patrol officer, then attempted to climb the median that divided the freeway, whereupon the officer had shocked him with a Taser. According to newspaper reports, Humphreys' ex-wife was told that the CHP officer had discharged his Taser twice.

When a Taser is used, the sheriff's office is required to create a printout documenting its use. Omalu waited six months for the printout, but it didn't arrive. At that point, and without more information to guide his autopsy, he examined Humphreys' preserved brain and found that he had suffered a mild traumatic brain injury — a concussion — which in rare cases can lead to death. He concluded that Humphreys' death had likely been caused by a head injury suffered during the crash.

It wasn't until two years later that Omalu finally obtained the Taser printout from an assistant district attorney. It had been created the day after the incident, and it showed that Humphreys had been shocked 31 times over a period of more than seven minutes. Omalu revised his autopsy: He now found that Humphreys had been killed by "repeated conducted electrical excitation." He also changed his recommendation concerning the manner of death from accident to homicide. Despite the new information, Sheriff Moore continued to classify the death as an accident.

Omalu was angered by this, and in a larger sense by what he considered Moore's dictatorial tendencies. He also balked at the county's practice of removing the hands of corpses to identify individuals, which Omalu considered unnecessary and, as he later wrote, "a form of body mutilation." But he remained in his post, convinced that his prime responsibility was to "protect the autopsy," as he told me. Omalu is not a particularly modest man, and he was certain that he could slowly change the culture of the sheriff-coroner's office from within.

All that changed in 2016. Three people in San Joaquin County died while being arrested by police, and in two of the cases, Omalu and Moore again clashed. The first case, in March, involved a man named Abelino Cordova-Cuevas. What happened between Cordova-Cuevas and the arresting officer is disputed. The Stockton Police Department claims that, after a traffic stop, the 28-year-old ran from his vehicle and fought with officers, which led them to use a choke hold and a Taser to subdue him. An attorney representing the family of Cordova-Cuevas, citing witnesses, claims that the man's hands were up in surrender and that he told officers he didn't have a weapon. Omalu judged the death a homicide caused by asphyxiation, compression of the neck, and blunt force trauma to the head, face, neck, and trunk. But Moore's office ignored his recommendation and concluded that the death was an accident.

Omalu began documenting his meetings with Moore in memos. "In my mind," Omalu wrote in one, "he seems to believe that every officer-involved death should be ruled an accident because the police did not mean to kill anyone." What he had once considered an anomaly had "become routine practice," he noted.

In November 2017, Omalu's colleague Susan Parson resigned, motivated in part by what she described as Moore's "intrusion into physician independence." Parson had come to the sheriff-coroner's office in 2016 for the chance to work with Omalu, but she had an adversarial relationship with Moore, who she felt tried to control her every move, and over the summer she had filed a gender-harassment complaint against Moore's office.

Several days later, Omalu resigned as well. The pair released to the press more than 100 pages of memos in which they described what they considered to be gross incompetence and interference on the part of Moore and his staff.

Moore vigorously disputes every one of Omalu's allegations. Asked about the missing Taser printout, Moore's office replied, "Neither the sheriff nor chief deputy coroner was aware of the printout until Dr. Omalu provided the information." Moore also strongly denies that he ever attempted to influence Omalu's findings.

In March 2018, as Moore came under increasing scrutiny, his office reclassified the death of Cordova-Cuevas as a homicide. In April, the county released an independent audit of the sheriff-coroner's office, spurred by the resignations. "The office must be and appear to be independent of law enforcement, particularly when investigating deaths in the custody of law enforcement or while in jail/prison," the auditor wrote. "This requires a complete shift towards a Medical Examiner System." The next month, the county supervisors unanimously endorsed such a shift. In June, Moore, a three-time incumbent, faced a retired deputy sheriff named Pat Withrow, whose campaign highlighted Omalu's resignation. In an upset, Withrow defeated Moore by 17 points.

Omalu's resignation made waves. The most consequential outcome, beyond Moore's ouster, was Senate Bill 1303, which would require California counties with populations greater than 500,000 to adopt a medical examiner system. Omalu worked hard to get it passed, but it was ultimately vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown, whose office issued a boilerplate statement that such decisions were best left to local jurisdictions.

"All you can do is do your best," says Omalu. His name is a shortened version of his father's surname, Onyemalu-kwube. In Igbo, the language spoken by Omalu's ancestral tribe in southeastern Nigeria, it means "If you know, come forth and speak."