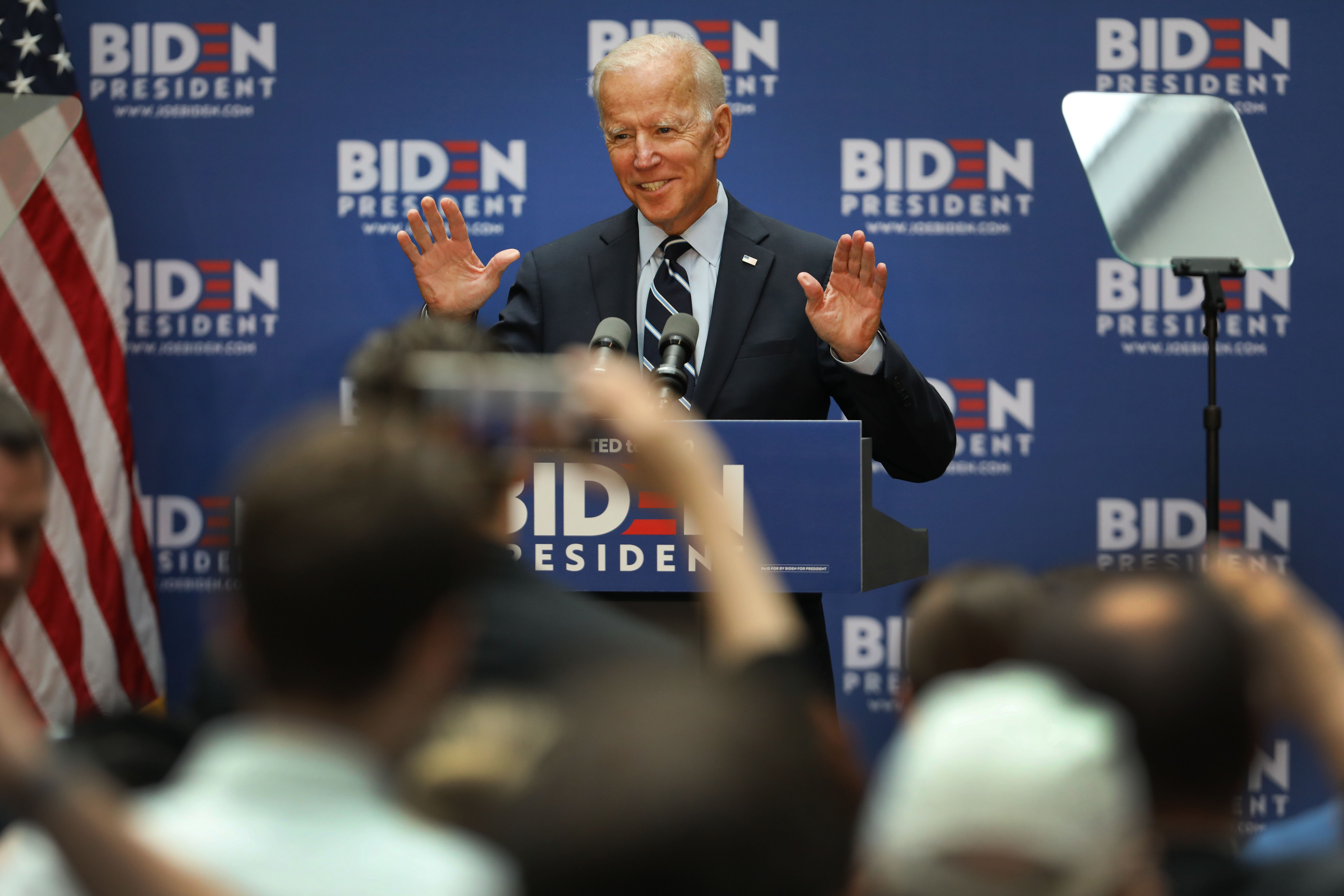

How a Trump recession could cement Biden's 2020 victory

During times of economic turmoil, voters want stability and caution rather than radical shifts in policy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"The economy, stupid."

In 1992, campaign strategist James Carville coined this memorable phrase, succinctly and colorfully summing up Bill Clinton's priorities as a presidential candidate. Thanks to a recession that started the year before, popular incumbent George H. W. Bush was made vulnerable to a challenge from a younger, fresher Democratic nominee. Clinton easily won the 1992 election and survived a disastrous first midterm by again focusing on the economy.

Nearly 30 years later, President Trump might find himself in a similar position as the first President Bush, only perhaps even more vulnerable to economic reversal. And Trump's economic woes could be former Vice President Joe Biden's 2020 gain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Trump has no war record nor splashy victory in a conventional war — as Bush had with Iraq in early 1992 when his approval rate spiked to near-universal acclaim — to cushion the blow of a recession. Trump ran on economic renewal and the potential for spectacular growth through deregulation, tax reform, and a pugilistic trade policy. With his other major campaign platform — immigration and border security — tied up in court actions and a stalemate with Congress, Trump needs the economy to keep performing at a high pitch.

Thus far, the economy has cooperated with Trump, even through the first stages of a trade war with China. Real wages have grown at a faster rate under Trump than with the previous administration, thanks to the elimination of the overhang of sidelined workers left over from the Great Recession. Four of the nine full quarters of the Trump presidency have seen annualized growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) of over 3 percent. Even in the midst of a tariff fight with China, the most recent quarter showed a surprising GDP growth rate of 2.1 percent.

Recent signals, however, have economists worried that the run of positive growth might soon come to an end. A research note from Goldman Sachs' chief economist warned that "fears that the trade war with China will trigger a recession are growing," while Bank of America economists raised the odds on a recession over the next year from 20 percent to 33 percent. "We are worried," they warned, especially since "our model likely does not fully capture the threat of U.S.-China trade tensions spiralling into a more severe trade war." Democratic presidential contender Sen. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.), whom PolitiFact credits with predicting the Great Recession, declared on Monday that "the odds of another economic downturn are high — and growing."

A recession in 2020 would be a body blow to Trump's campaign. A recession in 2019, or perhaps just the perception of its inevitability, might influence the Democratic primaries more than even Warren could predict. For insight, we can look back to 1992's Democratic primary and how Carville's axiom played out.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Democratic field in 1991-2 was nowhere near as large as in this cycle, but it had a surprisingly similar progressive bent. Early in 1991, fresh off his Gulf War victory and with approval ratings of 89 percent at one point, Bush seemed unbeatable, which discouraged more well-known potential candidates such as Mario Cuomo and Jesse Jackson from throwing their hats into the ring. Instead, Clinton and his successful Southern centrism squared off against only one other governor, California's Jerry Brown, at the time a favorite of left-leaning progressives. The three other major candidates in the race all came out of the U.S. Senate: Massachusetts' Paul Tsongas, Nebraska's Bob Kerrey, and Iowa's Tom Harkin, all of whom came from the party's more liberal and/or populist wing.

And yet, in the midst of a recession, the race took a surprisingly centrist tone. After recovering from the exposure of an extramarital affair, Clinton kept his focus on economic growth through traditional methods. This strategy turned out to be so successful that Brown tried changing tactics late in the primaries, swinging right to back a flat tax and abolishing the Department of Education, long a goal of Ronald Reagan conservatives. In the end, however, Democrats went with Clinton and his laser focus on the economy, a centrist who promised less of an economic revolution in the midst of uncertainty in the short recession.

If that same dynamic holds in 2020, it won't benefit Warren even if she wins the recession-prediction sweepstakes. Voters will want stability and caution rather than radical shifts in policy, perhaps especially after the drama and unpredictability of Trump's White House tenure. Almost the entire Democratic field has run hard to the left in order to out-Bernie Bernie Sanders; of the viable candidates remaining, only Joe Biden fits the mold. Biden also represents a restoration of the Barack Obama order, which is already attractive enough that Biden's opponents have been forced into the role of attacking Obama to fight Biden for the nomination.

That may not be a bad outcome for Democrats. Biden consistently polls as the most competitive candidate against Trump, and Biden has plenty of experience in working the Rust Belt states that Trump took in 2016. Primary voters seem inclined to choose Biden already, but economic turmoil may well cement his nomination as the safest port in a storm.

Perhaps Trump also senses that any economic upheaval will produce the toughest opponent possible in his re-election bid. On Tuesday, he ordered a delay on part of the next round of tariffs on Chinese imports, which are due to begin on September 1. The tariffs would have added 10 percent to the cost of $300 billion in annual imports, but Trump's new order postpones the penalties for around half of those imports — specifically on consumer items.

"We're doing this for Christmas season, just in case some of the tariffs would have an impact on U.S. customers," Trump said on his way to vacation in New Jersey. The new tariffs could have put a recession-starting decline into retailers' Christmas stockings and ruined their prospects for jobs growth in 2020. This move suggests Trump understands the dangers of the trade war dragging on for much longer.

For Trump, 2020 is entirely the economy, stupid, and especially if it produces an undamaged Biden as the candidate of welcome relief.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

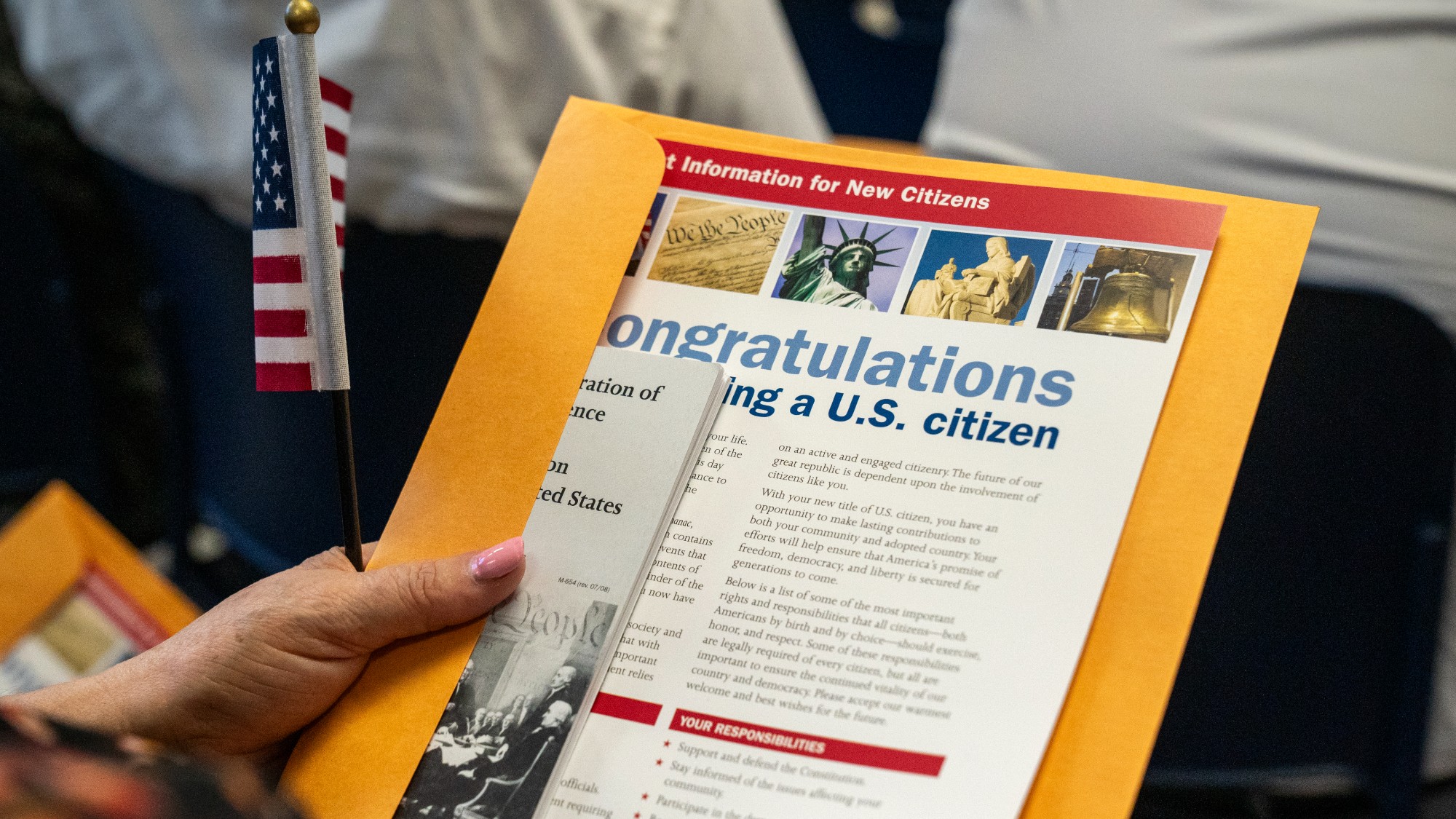

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugees

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugeesSpeed Read The memo also ordered all green card applications for the refugees to be halted

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame game

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame gameFeature Kamala Harris’ new memoir reveals frustrations over Biden’s reelection bid and her time as vice president

-

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day