India comes down with a virulent strain of nativism

Four million Indians are in danger of becoming stateless next month

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

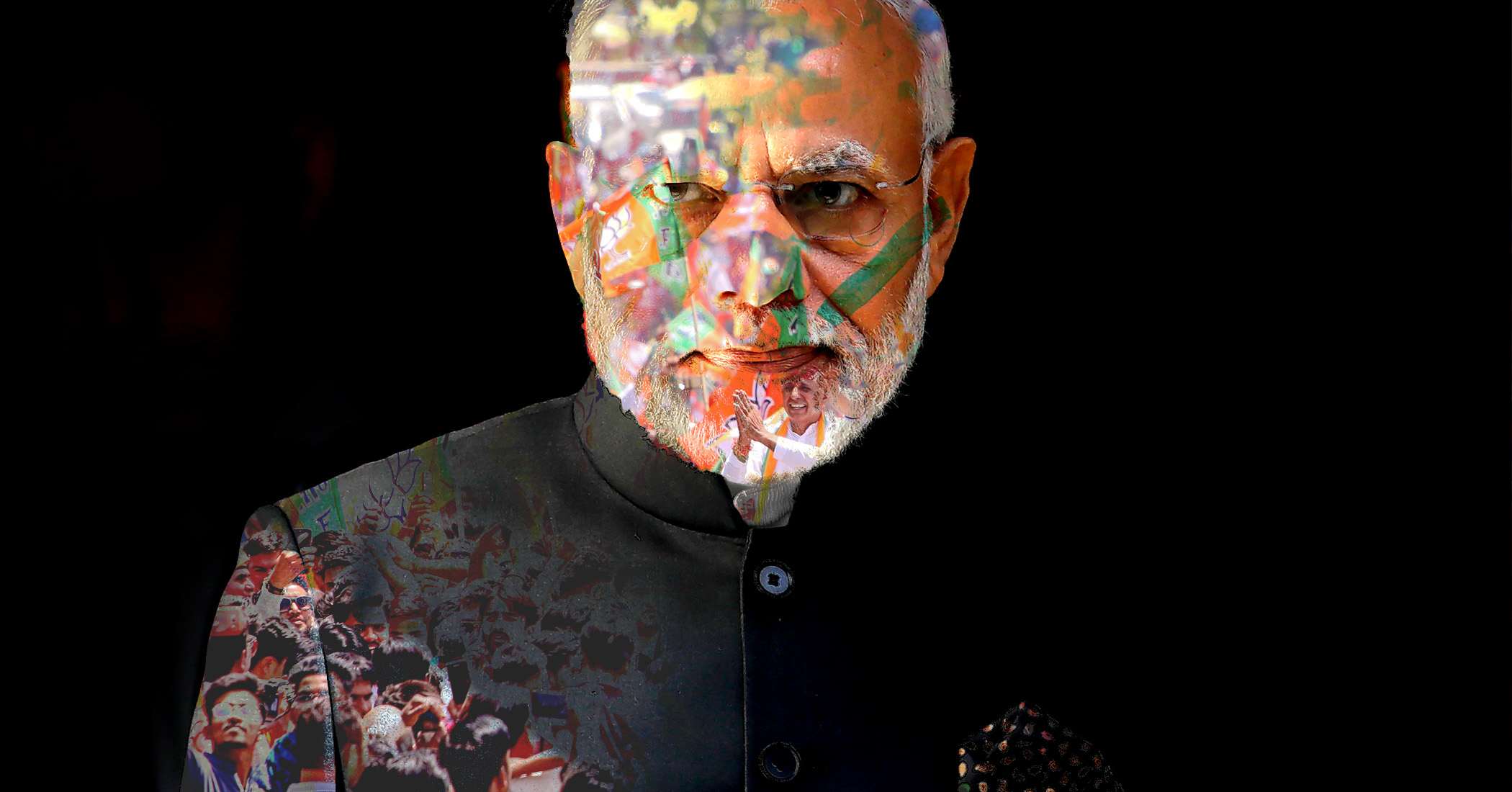

India, the land of Mahatma Gandhi, the patron saint of pluralism, peace, and tolerance, is on the cusp of achieving a dubious distinction: At the end of this month, it is poised to launch the biggest disenfranchisement drive in human history by stripping up to 4 million predominantly Muslim residents in Assam, an eastern province bordering Bangladesh, of their citizenship. And as if this weren't bad enough, Prime Minister Narendra Modi plans to go national with this crackdown.

This is shocking but not surprising. Modi, a Hindu nationalist, is riding the nativist wave around the world to advance his faith-cleansing agenda.

The Assam issue dates back to 1971 when Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, broke away from Pakistan with India's assistance and established itself as an independent country. Pakistani atrocities at the time caused some 10 million Bangladeshis, the vast majority Muslims, to flee to Assam and other Indian border states in what was the single largest displacement of people in the second half of the 20th century. Although around seven million of these refugees returned to their new homeland immediately after Pakistan retreated, some stayed behind in India.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This wasn't a major problem in states such as West Bengal that, except for religion, share Bangladesh's ethnic, cultural, and linguistic heritage. But in Assam, a remote and poor state in the mountains known for its tea estates, the presence of Bangladeshis who didn't speak the language and practiced a different religion created tensions with locals. The conflict escalated when the ruling Congress Party led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi handed voting rights — and, by extension, quasi-citizenship — to the refugees in what was considered a cynical move to expand her Muslim vote bank. Incensed, Assamese students in 1983 went on a killing spree, hacking nearly 2,000 Muslims — refugees and nationals alike — in six hours, one of the worst massacres in modern-India, rivaling the pogrom on Modi's watch in his home state of Gujarat in 2002.

The Congress government, deeply spooked, signed the Assam Accords with the student union in 1985, promising to update the defunct 1951 National Register of Citizens. This meant that all the 30-million-plus Assamese residents, equivalent of the population of Canada, were required to prove that their ancestors had lived in Assam from before 1971 or face not just being purged from the voter rolls but the country. Since Assam was granted an exemption from the rest of India's birthright citizenship, millions of people who were born in Assam and have known no other country could be rendered stateless.

Creating the register is a herculean exercise in a state (and country) with a high illiteracy rate and where many people don't know their birth dates, let alone keep copious ancestry records. That, combined with the fact that the Congress Party had no political incentive to ensure compliance, meant that the project didn't make much headway until the Supreme Court got aggressively involved.

Remarkably, the court didn't see its role as protecting due process rights to stop individuals' from being unfairly disenfranchised but as throwing out as many alleged foreigners as possible. A 2005 ruling scrapping a law that it said constrained the Indian government too much in expelling foreigners actually quoted the U.S. Supreme Court's notorious and largely discarded 1889 Chinese Exclusion decision that declared "the highest duty of a nation" is to "give security against foreign aggression and encroachment" including from "vast hordes" of foreigners "crowding in upon us." (Those who doubt America's effect on the world's moral compass should ponder that a U.S. Supreme Court decision was informing the Indian Supreme Court a century and a quarter later!) But impatient with the slow progress, in 2014, India's Supreme Court, whose chief justice is an Assamese who grew up in the heyday of anti-foreigner agitation and shares its goals, established a tentative deadline and a complicated process for completing the NRC.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One of the most chilling aspects of the NRC is that it requires individuals to prove they are citizens rather than the government to prove they are not, effectively scrapping the presumption of innocence even though rendering someone stateless means that they have no home nor hearth. It's a fate arguably worse than death.

But the court's aggressive timetable was manna from heaven for Modi who got elected that same year. Modi latched on to NRC as a campaign issue, promising to kick Bangladeshis, most of whom are Muslims, out of Assam. "They should be prepared with their bags packed," he told the gathered Hindu throngs at election rallies. Meanwhile, his Home Minister Amit Shah, echoing Trump's harsh anti-Mexican language, recently compared Bangladeshis to "termites" and "infiltrators."

The Assam government, which is controlled by Modi's party, finally released the NRC last year and set off a wave of panic because a whopping four million — 13 percent of the state's population — Assamese residents didn't make it on the list. But the NRC is so riddled with errors thanks to the omnipresent incompetence of Indian authorities that even the Modi government isn't eager to see it implemented in its current form. Even though the vast majority of those excluded are Muslim, there were more Hindus left out than it had expected. The court has given the government until the end of this month to release a final, cleaned up list.

What will happen to those who still don't make the cut?

The Modi government is trying to pass a bill that would hand automatic citizenship to all Hindu, Buddhist, Parsee, and Christian migrants from neighboring countries — everyone that is, except for Muslims. The Muslims, the only ones left if the bills go through, will have to appear before foreign tribunals for a final determination.

The tribunals are notorious for holding sham trials where officers who fail to convict the vast majority of petitioners are summarily fired. A Vice News investigation found that these kangaroo courts have no unified process to adjudicate petitions. Each tribunal makes up its own evidentiary rules, which are hard to fathom for petitioners, especially the poor ones who can't afford lawyers. Muslims especially have no chance of prevailing, given that nine of 10 were branded as foreigners in the sample of tribunals Vice investigated. One tribunal even convicted a veteran officer who had served in the Indian army for 30 years and had long ancestral roots in the state because he happened to be Muslim. Widespread outrage secured his release, but those who aren't so lucky are sent away to detention camps indefinitely because Bangladesh refuses to take them, especially if they weren't even born on its soil. Unsurprisingly, scores of people who didn't find their names on the NRC have committed suicide.

But that isn't stopping Modi from allowing Assam to add 200 new tribunals to the existing 100 and is planning 800 more for the future. He has also authorized 10 more detention camps.

And Assam is just a pilot test given that Modi's administration has already signaled that it wants to use the NRC process to give more states Assam's tools to root out "doubtful voters" and "illegal infiltrators" from the country. This may mean requiring every one of the 1.3 billion men, women, and children in India to prove their citizenship and would dwarf what is happening elsewhere in the world.

Modi's ambitions would not have reached such epic proportions if the nativist virus hadn't been raging in the West, particularly America. If a country like America that has long regarded itself as a nation of immigrants and has relatively strong institutional checks against government abuse can snatch infants from the breasts of migrant moms, it becomes very hard to restrain the Modis of the world. "When strong democracies resort to such harsh tactics against migrants," the London-based Amal deChickera of the Institute of Statelessness and Inclusion lamented over the phone, "what India is about to do in Assam begins to seem normal, not exceptional."

The West may have developed the current nativist contagion, but India has come down with a more virulent strain. And the consequences are going to be tragic.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Is a Putin-Modi love-in a worry for the West?

Is a Putin-Modi love-in a worry for the West?Today’s Big Question The Indian leader is walking a ‘tightrope’ between Russia and the United States

-

‘These attacks rely on a political repurposing’

‘These attacks rely on a political repurposing’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

'Total rat eradication in New York has been deemed impossible'

'Total rat eradication in New York has been deemed impossible'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Did Trump just push India into China's arms?

Did Trump just push India into China's arms?Today's Big Question Tariffs disrupt American efforts to align with India