How Elizabeth Warren could sweep the 2020 primaries

Could Warren run the John Kerry playbook?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Democrats, you might have heard, are headed for a long and brutal primary campaign, perhaps even a contested convention. Because of the party's proportional delegate allocation rules and the crowded field, as many as five or six candidates could amass enough delegates to stay in the race through the spring, all while President Trump raises hundreds of millions of dollars and waits to pounce on the nominee.

But what if this conventional wisdom is wrong? What if one candidate wins both Iowa and New Hampshire, and then the rest of the field rapidly melts away? With Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) surging in both national and early state polling, analysts are probably underestimating the likelihood that she essentially runs the table in next year's Democratic primaries and caucuses — like John Kerry did 15 years ago — despite the presence of multiple viable alternatives.

No two campaigns are exactly alike, and Warren is already doing much better than Kerry was at this point in 2003. But the two contests share some similarities: a sitting Republican president despised by Democratic activists challenged by a group of Democrats featuring at least half a dozen candidates who you could picture in the Oval Office.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Kerry, the eventual nominee, was nowhere near the top of the polling pile in the year before Iowa. By December, the clear leader was a once-obscure former governor of Vermont named Howard Dean. Unlike nearly all the other plausible candidates, Dean had opposed America's blundering rush to war with Iraq, and he used that anti-war stance to position himself as the progressive in the race despite a somewhat conventional record as governor.

Dean, like Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) would do 12 years later, was able to capture the imagination of Democratic partisans who felt betrayed and abandoned by the party leadership's seeming inability to stand firm against the Bush administration. The vote on the Iraq War resolution — amazingly, still a campaign issue 17 years on — passed with 81 Democratic votes in the House and 29 Democratic votes in the Senate. The subsequent and utterly needless war promised such predictable catastrophe that everyone who opposed it in real time was able to claim a certain kind of Nostradaman foresight. "What I want to know," Dean said in March 2003, "is what in the world so many Democrats are doing supporting the president's unilateral intervention in Iraq?"

This feels like unremarkable rhetoric from the standpoint of the present, but for Democrats in 2003 it was like rainfall after a long, earth-cracking drought. Dean's willingness to say that Democrats had lost their way ("I'm from the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party") quickly catapulted him from total unknown to frontrunner with a primary electorate that seemed hungry for a departure from the Clinton-Gore era of triangulation and compromise. He promised not just the standard recapture of the country but, as he said in his announcement speech in June 2003, "to take back the Democratic Party." He made universal health care the focus of his campaign, and although it looks like pretty weak tea now (it could have been called CHIP For All with its plan to massively expand access to the Children's Health Insurance Program), it was certainly better than anything Al Gore had put forward.

He was also the first national candidate to really make use of the internet. His supporters, the Deaniacs, would find each other and host get-togethers through Meetup.com, and Dean himself was an early adopter of online fundraising. When the grassroots organization Moveon.org held an online straw poll in June 2003, Dean won it, going away with 44 percent of the vote. He was a favorite of the emerging "netroots" bloggers. And for a time, Dean looked like he might roll through the primary field. He led in New Hampshire for months, with some polls showing him up as much as 21 points over Kerry. But his lead wasn't overwhelming — there were multiple candidates polling in the double digits heading into Iowa, and it certainly looked like Democrats were in for a long slog.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

They weren't. Two things happened in Iowa: Kerry claimed an unexpected victory there on Jan. 19th, and Dean's disappointing third-place finish sucked the air of his campaign. And it was that night that Dean unleashed his infamous "scream" at the end of his concession speech while trying to fire up supporters. While this so-called gaffe was nothing more than the microphone filtering out the crowd noise that Dean was shouting over, thereby making him seem unhinged rather than committed to being heard, it completely changed the tenor of the campaign. Dean had to endure weeks of mockery in the press for his "unpresidential" yelping.

Most surprisingly, national polls immediately elevated Kerry to the top, with a Newsweek poll taken just days after Iowa showing Kerry opening up a 30-12 lead over Dean. Kerry then won New Hampshire convincingly 8 days later, and following a string of increasingly lopsided losses, Dean dropped out after the Wisconsin primary on February 17th. When Edwards bowed out after Super Tuesday, Kerry became the presumptive nominee and the race was effectively over.

Could Elizabeth Warren run the Kerry playbook next year? In the primary era, candidates who win both New Hampshire and Iowa have generally gone on to easy victories (Kerry in '04, Gore in '00, Carter in '76), whereas a split decision seems to auger a long, close contest (Mondale-Hart in '84, Clinton-Obama in '08, Clinton-Sanders in '16). The one exception is the anomaly of 1992, when eventual nominee Bill Clinton lost both Iowa and New Hampshire. So Warren's path to an easy win probably involves winning both Iowa and New Hampshire, and then riding that momentum into a Nevada victory.

The assumption has long been that Warren would then have to survive a loss to Joe Biden (or perhaps Kamala Harris) in South Carolina before Super Tuesday on March 3rd. But what if, like Kerry, she gets a double-digit polling boost out of her early wins? Let's say she leads Biden 30-25 on Iowa eve, and then by mid-February has opened up a 40-20 national edge. Maybe she wins or comes in a close second in South Carolina and then cleans up on Super Tuesday, losing only two or three states. Especially if she wins California and Texas, her delegate advantage will be virtually insurmountable, the media narrative is likely to coalesce around the race being essentially over, and the remaining candidates will have difficulty convincing anyone of their viability.

Is this really plausible? Despite her recent surge, Warren still trails Biden slightly in national polling averages. While she leads in Iowa, she's still slightly behind Biden in New Hampshire and both Biden and Sanders in Nevada. There's plenty of time for Biden, Sanders, or even one of the lower-polling candidates to make a run between now and when voting starts. But there are reasons to think that she will continue to rise. She's making inroads with black voters who will be so critical in South Carolina and in many Super Tuesday tilts. She has the highest enthusiasm numbers of any of the Democratic candidates and is the predominant second choice of Sanders, Harris, and Pete Buttigieg voters. When YouGov asked respondents if they would be "disappointed" if certain candidates got the nomination, only 7 percent said so about Warren. Sixteen percent expressed disappointment with a Sanders nomination and 22 percent with Biden.

There's a reason the betting markets have converged on Warren: She seems to have the most appeal to the broadest possible set of Democratic primary voters. She's a policy radical who has nevertheless remained in good standing with the party's kingmakers, meaning that both committed progressives and more cautious rank-and-file partisans can feel comfortable with her. Her numbers against Trump are improving. And she's run a relentlessly focused campaign, using gimmicks like taped thank-you calls to small donors and legendary selfie lines for supporters to get a picture with her to great effect.

While I wouldn't put money on Warren having the nomination wrapped up by Super Tuesday, I also wouldn't bet against it.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

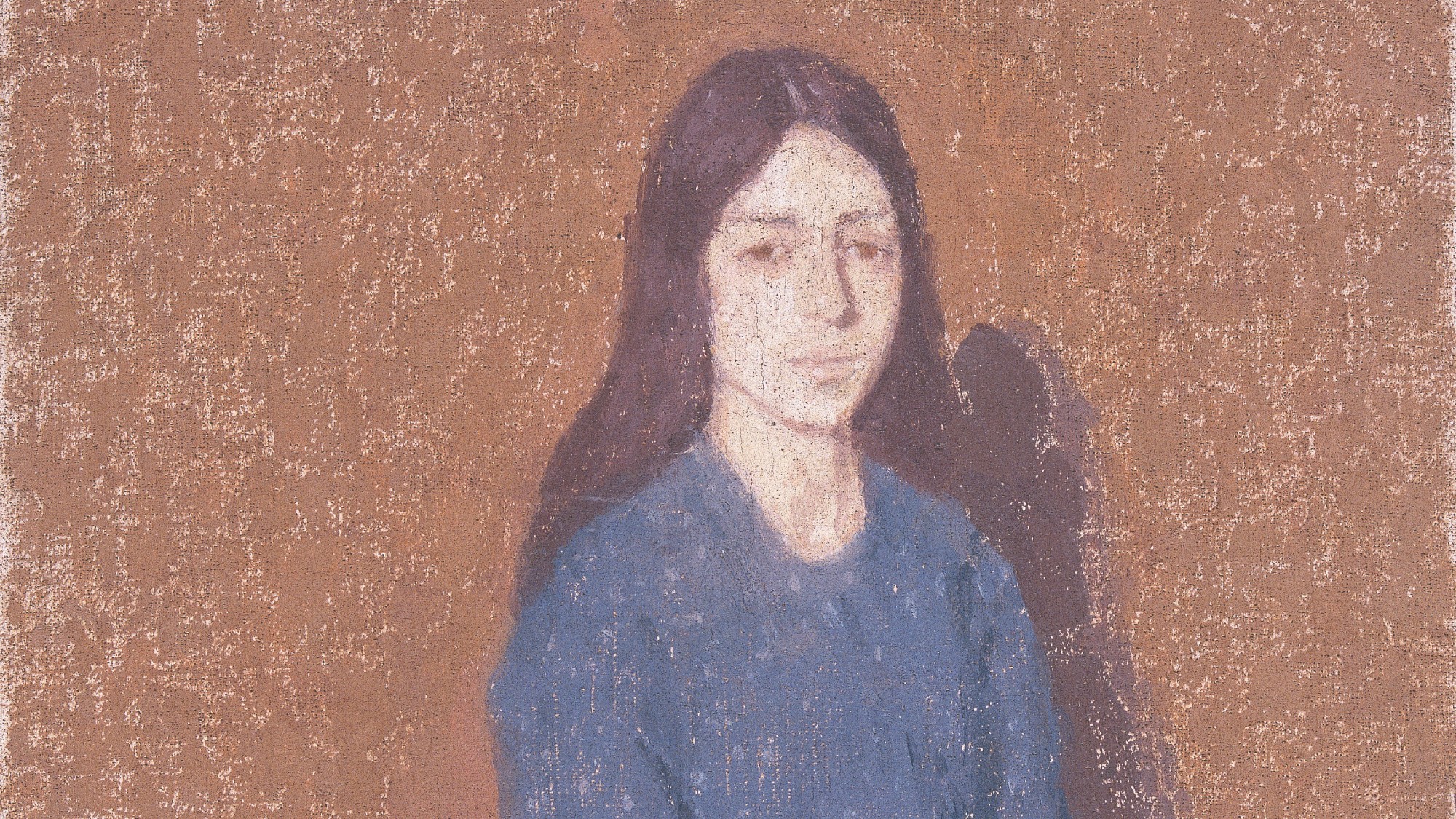

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Trump’s poll collapse: can he stop the slide?

Trump’s poll collapse: can he stop the slide?Talking Point President who promised to ease cost-of-living has found that US economic woes can’t be solved ‘via executive fiat’

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration