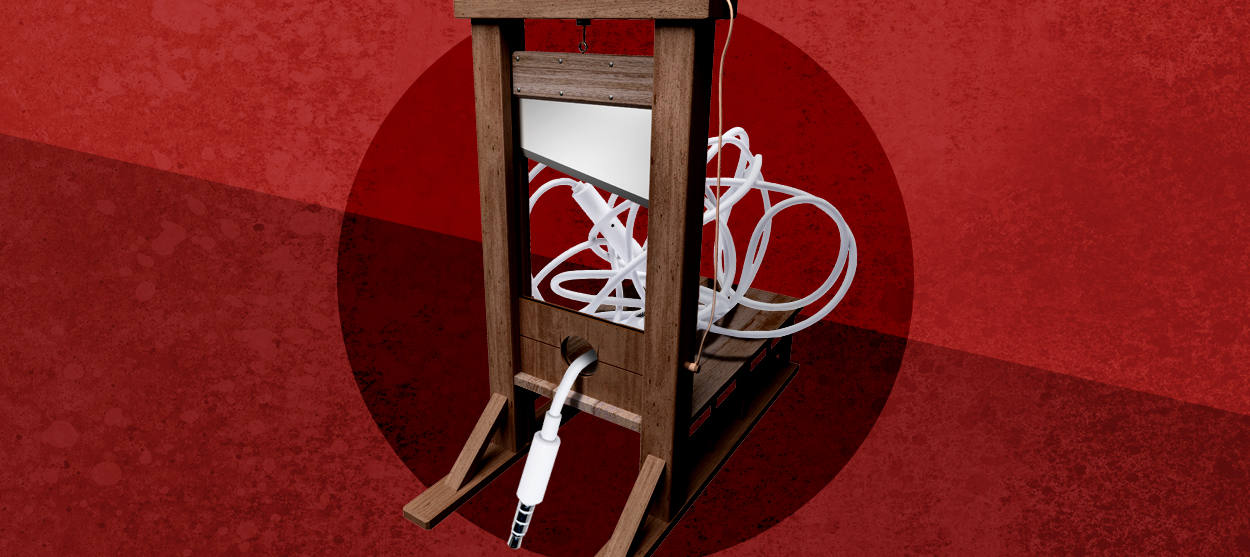

How the tech duopoly killed the headphone jack

The real consequences of 'vertical integration'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The reviews are in and they are almost universal: Apple's new AirPods Pro are great. And why wouldn't they be? Despite many flaws in the original AirPods — poor fit and mediocre sound quality, to name a couple — they quickly became the most popular headphones in the world. All Apple had to do was make some obvious changes and apply their considerable engineering talent and, presto, they have another hit.

It's not just engineering quality and design that has millions of people ready to pony up a full $250 for the new earbuds, though. Rather, despite not being quite as good as some competing models from Sony or even Amazon, the AirPods are like all Apple products: they work best with other Apple products — pairing quickly, activating Siri, and so on. It's convenient — and perhaps all a little bit too neat. Apple removed the headphone jack from their phones, ostensibly to make thinner devices, and then released expensive wireless buds that yet again take advantage of the walled garden of Apple. Now the iPhone 11 phones are out, thicker than last year's model, and the AirPods Pro are the perfect match for your $1,000 phone.

The problem? When Apple and Google control the two major computing systems, things that work best with those systems tend to be the ones that succeed. So first, companies kill the headphone jack — and soon, perhaps, they will also start to kill competition.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This isn't merely theoretical. Google famously flopped in the smartwatch market, in large part because, unlike Apple, it had no in-house department to design chips, and instead had to rely on partner Qualcomm, who haven't been able to compete with Apple for years. That's the corporate case for vertical integration: when you control all the parts, you can make better stuff.

Now, looking to make up for its past mistakes, Google has bought FitBit, the maker of wearable fitness trackers and smartwatches. Just as antitrust chatter starts to ramp up amid worries of tech's increasing consolidation of power, one of the world's largest companies swallows an ostensible competitor not only to absorb talent to make its own smartwatches, but also to hoover up its data.

The smartwatch example is illuminating. More than any other tech, smartwatches currently rely on the smartphone they are paired with for much of their functionality. An Apple Watch only works if you have an iPhone — and speaking as an Apple Watch owner, it's a powerful form of lock-in. In one sense, it's about tech companies pairing products with each other because they'll work more effectively together. But it also shows how the vertically integrated system encourages both users and companies to form little silos of tech which end up discouraging interoperability, and with it, competition.

So we're left with a situation in which a Google thing might work better with a Google thing, but if you want to buy a phone from one company, headphones from another, and a smartwatch from another, they're never going to work quite as well as if they're all from the same company. That's not a monopoly exactly, but it is a subtle or passive form of coercion.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Making matters more complicated is the way in which services and digital assistants get baked into operating systems. Google's Assistant, for example, works best when it knows more about you — specifically, your appointments through Gmail and Google Calendar, your interest via search, and your whereabouts and travel habits through Maps. Similarly, Apple's AirPods can raise Siri hands-free but not Google's Assistant or Amazon's Alexa. It's all about tie-in, and in this case, "tie-in" means "less consumer choice."

What this means is that there isn't so much competition between individual products — between this phone or that, or these headphones or another — as much as between ecosystems: Apple's, Google's, and perhaps Amazon's and Microsoft's — though the latter two don't really have their own as much as piggyback on the other two. That isn't really competition; instead, it's a scenario in which the ecosystem owners either swallow or overshadow those who oppose them.

And that is how we end up with a world in which a universal standard — the good old headphone jack — disappeared and we are instead left with a series of wireless earbuds from Apple, Samsung, Amazon, Microsoft, and more that are each less effective when paired with "opposing" ecosystems.

Ideally, the tech world would agree to some sort of standard, but given their both short- and long-term incentives to create their own internal and inaccessible protocols, that goal is likely a long way off, if it ever comes at all. Just as Google shouldn't be allowed to acquire a competitor, companies should also have to make at least some gesture to better interoperability — a task that is only suited to regulators who, it seems, have been caught flat-footed by the pace and scale of digital. The new AirPods might be great — but what would be better would be tech that didn't so eagerly try to put everything behind a wall.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Navneet Alang is a technology and culture writer based out of Toronto. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, New Republic, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt.