Does social media silence grief?

On tragedy and sadness in the age of Twitter and Facebook

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

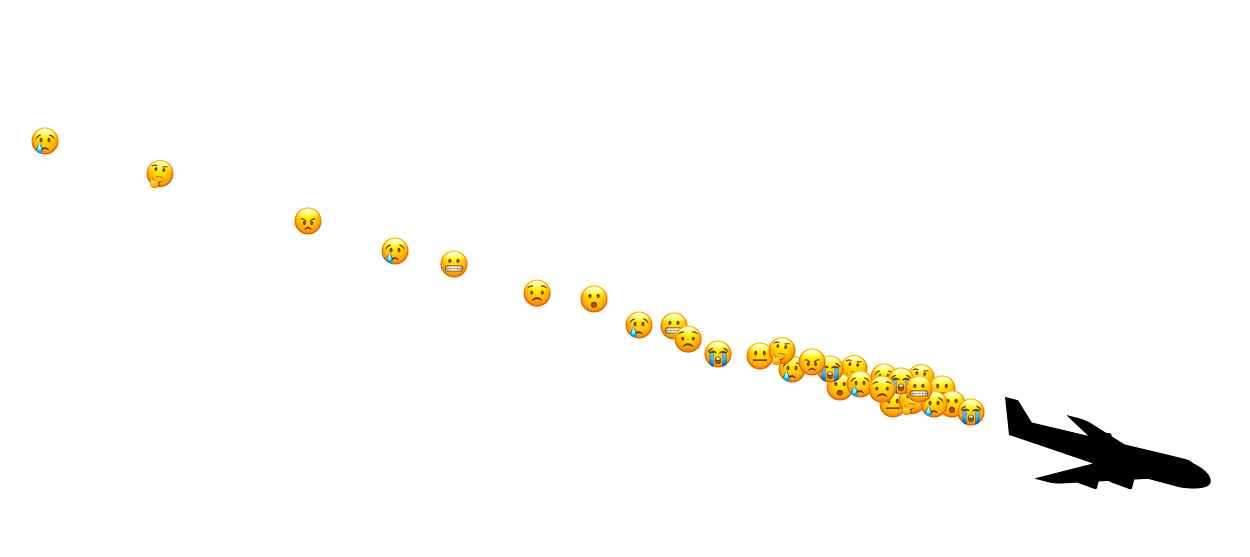

When Ukrainian Airlines flight 752 was shot out of the sky this month, and all 176 people on board perished, my social media feeds initially carried on as if everything were quite normal. Despite the awful tragedy, there were the usual jokes, the squabbling, the self-promotion. It felt eerie, strange, surreal, as if all that death didn't matter.

It's not that I am unaware of this tendency online. It is loosely part of what scholars refer to as context collapse: the flattening of a whole variety of audiences and ways of speaking into one, unified stream. In this case, it seems people I saw online felt this disaster was just another awful thing happening in a faraway land, and thus carried on with their day. I've seen it happen hundreds of times before.

But as a Canadian, the disaster felt particularly painful; 57 people on board were Canadian citizens, and a full 138 of the passengers were supposed to be on their way to Toronto via a connecting flight. That flight still arrived at Toronto's Pearson International Airport. It was full of empty seats.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There is much to consider about the tragedy: why Iranian airspace was still open in a moment of chaos, whether American action was a precipitating factor, and how or if any sort of closure might be achieved. But another question to emerge is whether or not experiencing such awful news through the lens of social media can somehow numb or inure us to it — that in flattening all that is happening into a single experience, social media leaves us struggling to distinguish between the ordinary, the sad, and the truly awful.

Of course, trying to judge or control reactions to tragedy is, at best, a fool's errand. In grief, some cry and some make jokes, and that is what it is to be human; social media simply exposes us to that inevitable fact. So to ask whether or not people are responding appropriately to a disastrous event is always going to involve a bit of guesswork, or even projection.

We can, however, at least pay attention to what has changed. Writer and digital technology critic Nicholas Carr recently wrote on the topic of how we judge importance on social media. Building on the idea of context collapse, Carr instead puts forward the idea of content collapse: what he defines as "the tendency of social media to blur traditional distinctions among once distinct types of information — distinctions of form, register, sense, and importance."

In part, content collapse is a result of the aesthetics of social media: Everything looks the same and even has the same sort of tone. Perhaps this is why social media is so often home to hyperbolic language — everything is perfect, the best, the greatest of all time. You need superlatives to break through the sameness. This does perhaps alter how we experience the wide variety of life. Suddenly, everything is at the sped-up, high-pitch tone of Twitter.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Canada unfortunately had another such incident with the Air India disaster in 1985. Still Canada's deadliest terrorist attack, it occurred when Khalistani extremists blew up Air India flight 182, killing 329 people. The attack stands out in Canadian history for a number of reasons, but not least because the muted response and botched investigation seemed clearly inflected by racism — by a sense that the people on board weren't really Canadians.

A similar narrative began to emerge after the flight 752 disaster. Most of the people on board were of Iranian descent, and it was hard not to wonder whether that fact played a part in the strange response. Some op-eds used the tragedy to make points about military power that felt unseemly, others felt the need to remind Canadians that the victims were their fellow countrymen and women.

But things did eventually feel slightly different. After an initial period of silence, official channels — city mayors, the prime minister, the mainstream media — started to talk about the tragedy as a national one. A successful restaurateur with a history of philanthropy started a fund to help the victims' families. The country mobilized — if belatedly.

Perhaps that, too, is an effect of social media: the ability to get the word out, to change how we think about things. If social media's kaleidoscopic cacophony has the ability to fracture a sense of shared narrative, then it also has the capacity to push things into it, sway it.

It's an odd dichotomy and I'm not sure what to make of it; it certainly seems to resist labeling social media with any sort of neat demarcation between "good" and "bad."

But something is still troubling nonetheless — if not the flattening of world events, then our ability to hold on to their gravity, their depth of awfulness. Hundreds of people in the victims' families around the world had their lives torn apart by what appears to have been an error in a tense geopolitical moment, and the tragedy was quickly eclipsed by all the other news happening right now. Social media seems to have accelerated how we experience loss — made us process and feel it all at lightning speed, and perhaps without actually truly reflecting or grieving. I mean, who even has the time?

We are not without solutions, though. As users, we can also do what little we can to inject some sense of continuity or duration into our feeds: to keep what we believe should be remembered top of mind. It would be a start. And perhaps it's just wishful thinking that something can be done to quiet the noise of social media. But trying is better than letting things stay the same. Right now, even the gravest of tragedy feels like sand, slipping through our fingers, and our ability to feel is falling away.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Navneet Alang is a technology and culture writer based out of Toronto. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, New Republic, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day