Give Harriet Quimby her due

The pioneering aviatrix whose greatest feat was overshadowed by the sinking of the Titanic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Late at night on April 14, 1912, as the Titanic blazed toward its frigid destiny somewhere in the North Atlantic Ocean, Harriet Quimby was sleeping. The weather off the coast of England had been terrible all week, stormy and overcast. Not good flying weather. And Quimby — who'd been called a "lady bird," "airship queen," aviatrix, newspaper woman, and nicknamed "Dresden China" on account of her fair skin — had one more title she wanted to add to the list. Pioneer.

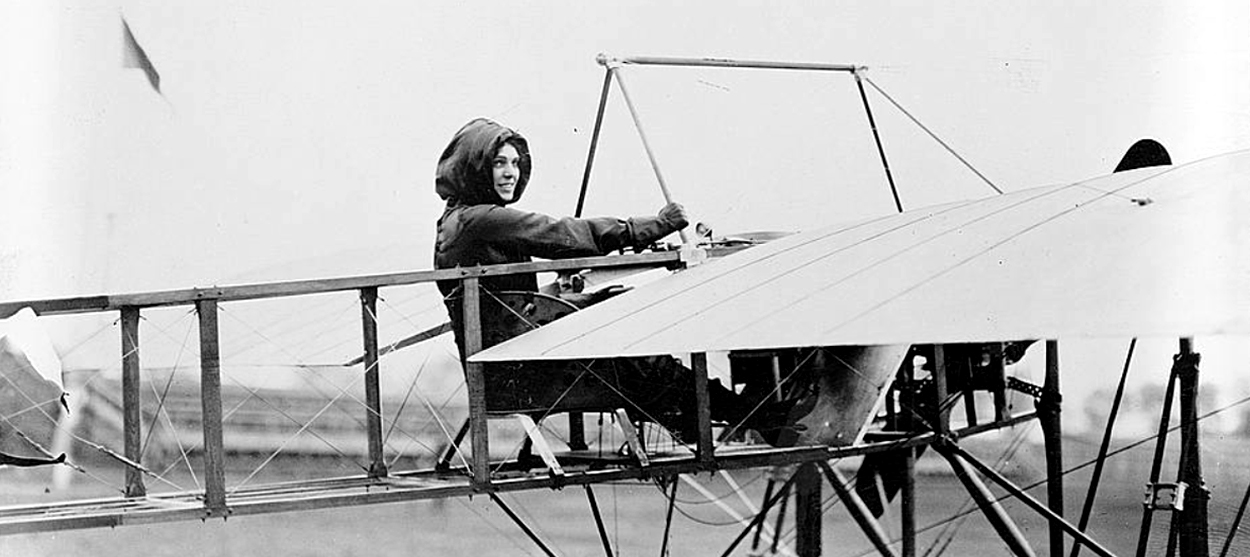

In the early morning hours two days later, on April 16, as every newspaper in the world set their type to announce the "greatest marine horror in history," Quimby stepped into a Blériot XI, a machine her contemporaries still described with that extra syllable, aeroplane. It was cloudy in Dover, but 23 narrow miles of water beckoned and the winds seemed alright. She took off, her goal known only to two female friends and a handful of male ones in order to prevent anyone from beating her to it. When she next touched land an hour and nine minutes later, she was in a fishing village in France, beaming amid a crowd of surprised fishermen, now the first woman to have done what only a handful of men at the time had managed: fly across the English channel.

In April 1912, Quimby was already renowned for being the first woman in America to have received her pilot's license, and like Amelia Earhart — that far more famous aviatrix who would follow in her footsteps — she would go on to die dramatically and tragically, doing what she loved. But Quimby has never received the level of recognition she deserves in the American pantheon, despite her extraordinary life. There is no flashy biopic about her spectacular adventures, no airport named in her honor. Literature on her is limited, apart from a smattering of children's books; talk of a potential biography, announced in 2015, has since gone quiet.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Still, during her time, Quimby was a celebrity; it's not difficult to find articles from the early 1900s that breathlessly followed her career. Human flight, after all, was still an exciting new concept when Quimby attended an international aviation meet at Belmont Park in New York, where she first fell in love with the sky. But when she was born in 1875 — likely in Michigan, although her lack of a birth certificate has led to some dispute — the Wright Brothers were still 28 years out from liftoff in Kitty Hawk.

Quimby had always been adventurous, though, even before the airplanes. The grandmother of Quimby's would-be biographer, Allyn Mark, worked with Quimby at the Sleeping Bear Inn in Glen Haven, Michigan, one summer and when a theater troupe came through town and stayed there, Quimby up and left with them, following one of the actors all the way to San Francisco. The relationship didn't last, but Quimby found work on the West Coast in 1902 writing for a number of papers in the Bay Area. She also met and befriended another struggling actor, one D.W. Griffith.

By 1903, Quimby crossed the country again to New York City, where she began working at Leslie's Illustrated Weekly as a drama critic, although she spent her free time, by all accounts, racing about in cars. In 1910, she attended the fateful air show in Belmont and discovered a new source of adrenaline, having been awed by the pilot John Moisant, who won the day's race around the Statue of Liberty. Quimby begged Moisant to teach her to fly, but he would die in a crash before he was able to do so. Quimby and her friend, Moisant's sister Matilde, took up lessons with John's brother Alfred instead.

Quimby took to airplanes like she'd been born to fly, although her exploits were, as was typical, not without some drama. In May 1911 — around the time she was also penning silent film scripts for Griffith — she crashed her plane, snapping a wing but making it out unharmed aside from a few bruises. "She thinks flying is safer than riding at high speeds in an automobile," remarked an item in Iowa's Evening Times-Republican in June 1911 under the headline "American Girl Is Learning to Run Aeroplane; Seeks License." The next month, a new headline had replaced it: "BIRDWOMAN FAILS. NO LICENSE YET," announced the Salt Lake City Tribune, adding that "Harriet Quimby, the only woman [to be up for a pilot's license in the country] fell short in the accurate landing test by 40 feet," making it "necessary ... to try again." In August, at last, success: "America's First Birdwoman Is A San Francisco Girl," proudly read the front page of the San Francisco Sunday Call, alongside an illustration of Quimby. Except instead of arms, in the drawing she had wings.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Luckily for advertisers, in addition to putting "pride in the breasts of American sportsmen," Quimby was a beauty. "She is rather blonde, with sunburned complexion, slim and not above medium height," observed one columnist in The New York Tribune. "She has a brilliant, frequent smile, good teeth, and fine, keen eyes." The Sunday Call wrote that her "striking beauty gave inspiration" to the papers' artists. Her plum, feminine flying outfit was also eye-catching. "She didn't like the awkward suit of the French women aviators, so she went to a man tailor in New York and together they figured out a single piece suit that fits snugly and has no loose flapping parts to get caught in the wires or by the propellers or any of the machinery, and which leaves the feet and legs free for their part of the work," explained the Sunday Call. She would wear the costume when she modeled for Vin Fiz grape soda.

Her fellow birdwoman, Matilde, meanwhile, had given up flying. "The earth is bound to get us after awhile, and so I shall give up before I follow my brother," the grounded aviatrix said.

When Quimby finally achieved her dreaming of crossing the English channel, though, it was overshadowed by maritime tragedy. Notice of her feat got only passing mention on front pages otherwise crowded with headlines of horror: "Newest and largest steamer in the world sinks before vessels hurrying to aid reach scene of collision." She failed to earn proper notice for another reason, too. Men considered the skies to be their own dominion: "All male aviators dislike seeing women 'in the air,'" wrote The Salt Lake City Tribune in the opening paragraph of its notice on Quimby's accomplishment. The report in The New York Times was even worse, PBS notes, with the writer claiming "exultation is not in order" for Quimby because "just a few months ago this same flight was one of the most daring and in every way remarkable deeds accomplished by man … The flight is now hardly anything more than proof of ordinary professional competency."

The next time Quimby made headlines in 1912, it was in the screaming, sensational font of disaster too. While flying her new 70-horsepower Bleriot monoplane during a Boston airshow, the 37-year-old Quimby hit turbulence. "Heading back into the eight mile gusty wind, Miss Quimby started to volplane," recounted The Rock Island Argus. "The angle was too sharp and one of the gusts caught the tail of the monoplane, throwing the machine up perpendicular. For an instant it poised there. Then, sharply outlined against the sun, [Quimby's passenger] was thrown clear of the chassis, followed almost immediately by Miss Quimby." They fell 1,000 feet before the eyes of thousands of horrified spectators, into the five-foot-deep tidal waters of the muddy Dorchester Bay.

"[Quimby] was obsessed by the notion of a mischievously malicious giant hand stretched forth from the clouds behind her, snapping its great fingers perilously near her outstretched planes, or, with the tip of one of those immense digits flipping upward the tail of her craft as though for the pleasure of seeing it dive headlong to the earth below," one obituary would say, adding that "at last that giant cloud-finger succeeded in its experiment."

But such a superstitious portrait doesn't quite fit. During her life, Quimby's uncanny premonition was another sort, of what the future held for her fellow lady birds. As she told one interviewer a month before her death: "I have never met a woman who doesn't want to fly."

Fittingly, written on her gravestone is her immortal reassurance to anyone who trembles before spreading their wings: There is no reason to be afraid.

Want more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal