The 7 deadly sins of pandemic

Now, perhaps more than usual, we can hear temptation crouching outside our door

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

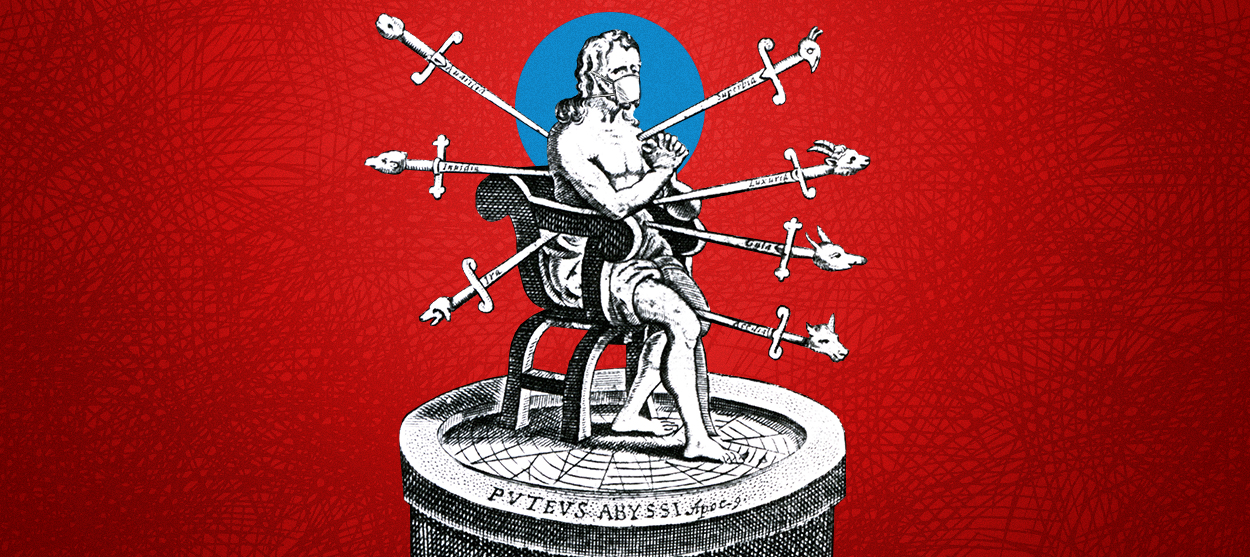

The Bible speaks of sin in many metaphors — fire, worm, poison, refuse — but among its most vivid is the picture of evil as a predatory beast.

"[S]in is crouching at the door; and its desire is for you, but you must master it," God warns Cain a verse before he murders his brother Abel. "Discipline yourselves, keep alert," advises the Apostle Peter millennia later, for "Like a roaring lion your adversary the devil prowls around, looking for someone to devour."

The hunt is on even in the best of times, and in this pandemic, we prey are flagging in the chase. This week, I happened to reread the list of seven deadly sins, a traditional (though not directly scriptural) Christian categorization of vices. I saw in each a way we're stumbling, a way the pressures of pandemic have us cornered for the bite.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Take gluttony, the first sin of seven nipping at our heels. Gluttony sprang up as soon as distancing rules were announced. Its province is not only food: Gluttony can entail selfish and wasteful over-consumption of any kind. The toilet paper hoarding was nothing if not gluttonous, so too any buying behavior that prompted stores to assert purchase limits. The gluttony of some thus constricted fulfillment of others' legitimately greater needs. Gluttony is as well the ever-present temptation of unlimited entertainment, as our use of "binge" has long confessed.

Though it's often an element of gluttony, greed is its own sin, too. There is a greed in hoarding, but of a simple, self-centered sort. The hoarder doesn't think of how his greed harms others, only how it benefits himself. Sicker, then, is the greed of advantage and fraud, both of which have taken the pandemic as occasion to flourish. This is the greed of the Tennessee brothers who collected 17,700 bottles of hand sanitizer in their garage in early March, intending to sell it to the desperate at an exorbitant markup. It's the greed of coronavirus testing and remedy scams, pitches of pills, salt, and toothpaste as false cures. But there's more mundane greed here, too: the greed of not tipping the delivery driver well. The greed of not offering help to family and friends who have lost their jobs while you still have yours. Greed, as the confession from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer says of sin more generally, is in both "what we have done" and "what we have left undone."

Wrath, by contrast, never wants its expression left incomplete. Incessantly, as C.S. Lewis wrote in a poem on the deadly sins transformed, it is "postulating still/Inexcusables to shatter." And in this pandemic, inexcusables abound. My extended family has argued over whether and how to comply with stay-at-home orders, and we're hardly unique in such acrimony. "My husband and I have opposite views on dealing with social distancing," begins a recent letter to The Atlantic's "Dear Therapist" column. "When we try to have a discussion," the correspondent continues, "it turns into a fight." Not often does the political so doggedly meddle in the personal — and with such high stakes. Not often do we feel we have half the country at our back, verifying and justifying our fury.

The public dimension feeds the next sin, too. Pride as sin is self-aggrandizement — see our Insta-boasts of workouts completed and dinners made — but, more gravely, it is hubris. It's unjustified confidence in our own judgment, unmerited certainty in our understanding of this extremely uncertain situation. This pride is a kind of self-deceit, and it is found across the coronavirus debate. It convinces us we can brush off remonstrance and refuse to heed caution. We can ignore data that conflicts with our conclusions and testimony that fails to echo our feelings.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The inverse of self-aggrandizing pride is sloth, but sloth is not limited to mere laziness. More substantively, sloth is a surrender to apathy, especially apathy toward doing needful good. Sloth is acedia, which Biola University professor J. L. Aijian describes at Christianity Today as "the feeling of dread when faced with certain tasks or the desire to distract yourself with easier or more pleasant work." It is a refusal to care which may take the form of capitulation to distraction or indulgence in immobility. Sloth may have an element of fantasy: daydreaming about what you'd like to do as an escape from what you ought to do.

Envy runs on fantasy, too, and the pandemic has given every one of us a shining object of endlessly defensible envy: our own lives, three months ago. It doesn't matter how much or little has changed day-to-day. Any difference is enough for this discontent. Then there's envy in its more familiar form, the envy of each other. Those of us stuck inside can envy the freedom of those who must go out; those out can envy the safety of we who are in. And this is a particularly difficult envy to resist because these are licit wants. Freedom is good! Safety is good! We are not wrong to want whichever we don't have. But that want becomes sin when it is bitter and resentful, precluding joy in another's circumstance and gratitude for our own.

Last is lust. We usually think of this seventh sin in sexual terms — here, the pandemic-produced spike in pornography consumption and the newly digital strip club. Yet lust goes beyond lechery. The prudes among us may lust after the gaudy wealth which backdrops celebrities' shallow messages of pandemic solidarity. And too many of our political leaders have let no opportunity to display their lust for power go unseized. The lion of Peter's warning is a pursuit predator, but lust's strategy is ambush predation. It lures you, closer, closer — "If I could just reach..." — until snap! It savages your character and leaves your innards exposed for all to see.

This list of seven sins has resonated with people in all sorts of circumstances for millennia, of course. But now, perhaps more than usual, we can hear temptation crouching, slavering at the door. Its desire is for us, but, God help us, we must master it.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.