Joe Biden's coronavirus rescue plan isn't bad. But it could be better.

Time for a child allowance for all American parents

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President-elect Joe Biden announced Thursday night his plan to combat the coronavirus pandemic and repair the economy. The proposal would cost $1.9 trillion — a giant package, more than twice the size of President Obama's Recovery Act. It would extend some of the relief measures introduced in the CARES Act last year, and would add a number of other badly needed support systems.

In broad strokes, the plan is in the right ballpark, and many of its stipulations are excellent. However, it falls short in a couple places, most notably in the size of its direct assistance checks and its temporary boost to the Child Tax Credit.

Let me start with the details of the full package. Biden would spend $400 billion on vaccine distribution, testing, paid leave, and to help schools and frontline health workers. He would increase the federal boost to unemployment insurance from $300 to $400, plus extend it to September, and do another round of checks. He would extend the moratorium on evictions, set out $25 billion for rental assistance, increase food stamp benefits, and increase the minimum wage to $15 per hour. State and local governments would get $350 billion to help stave off catastrophic cuts, and transit systems would get another $20 billion. (There is a lot more, but those are the main points.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That is all to the good. The vaccine rollout plan is elaborately detailed, and appears (to my informed amateur eye) to hit all the right points. The $15 minimum wage is a great idea, as is the boost to unemployment. An extension of the eviction moratorium is vitally important, as is aid to states, cities, and transit authorities.

Now, the problems. Biden would send out a round of $1,400 checks, which in addition to the $600 round approved in December would make for a total of $2,000. This sparked an immediate debate over whether this was a climbdown from the Democrats' previous position of sending another $2,000 (for a total of $2,600). For my part, I suspect this was simple sloppy messaging. When President Trump initially proposed $2,000 checks, that was as part of the pandemic rescue package that later passed with only $600, so the ensuing supplementary bill that got wide discussion as being about $2,000 also only had $1,400 in new money.

That said, regardless of intentions, many Democrats have been saying "$2,000 checks" without qualification over and over long after the last rescue bill passed. To the lay person, by this point it surely sounds like they meant a fresh additional $2,000, thus passing only $1,400 now would surely seem like a broken promise to many. On the other hand, another $600 is not that much money, and would be economically beneficial anyway. It would be greatly helpful for the poorest Americans, and there is every reason to get everyone's savings accounts nice and fat now, so that when everyone is vaccinated the economy can pop back to full employment at the greatest possible speed.

But that is a comparatively small problem compared to the changes to the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Now, Biden has some good basic ideas: He would increase the credit from $2,000 per child to $3,000 (and $3,600 for children under six), and make it fully refundable — meaning even if you have no tax liability at all, you still get the full amount in the form of a direct payment rather than a reduction in tax, which is not currently the case. That is a great change because it will include the poorest people in the country, who are currently left out because they have little labor income and thus pay no income tax.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, doing this child benefit as a tax credit is still problematic. First, it will be complicated to claim: Research demonstrates that a large fraction of people fail to claim this kind of tax credit because they are unaware they exist or file their paperwork improperly — up to 22 percent, according to the IRS. That will be even worse with a brand-new program that only lasts for one year (more on this below). Second, it will be inaccurate. Biden's team is reportedly looking to get money out the door immediately (as opposed to waiting until the 2022 tax season, as is normally done), but because tax credits are calculated based on the prior year's income, this will likely require people to file their estimated tax liability with the IRS, and then adjust things when they file their normal taxes. This would be difficult to do at the best of times, much less during a global pandemic, and there are certain to be many qualified people left out as a result.

Much worse, Biden would only do this expanded CTC for a single year. The justification, presumably, is that this is meant to remedy the effects of the (hopefully) one-time pandemic. But this policy is based on a similar proposal from Senator Michael Bennet (D-Colo.), who came up with it years ago as something to deal with America's extremely high rate of child poverty. And he was correct — we need child benefits for now and all eternity, not simply to deal with the pandemic, because children always cost a lot to raise yet bring in no money. Even David Brooks agrees.

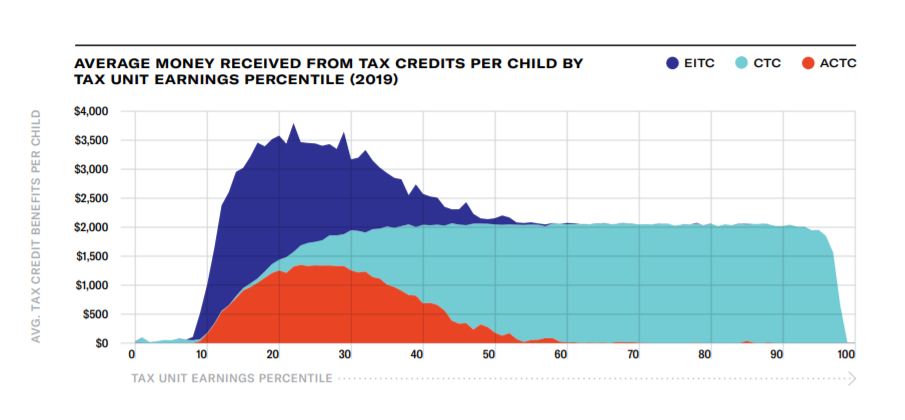

As Matt Bruenig argues in a recent paper for the People's Policy Project, there is a far better option: a permanent, universal child allowance. The CTC is just one of several tax credits for children, along with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and others, which combine together to create a super-complicated mess of differing eligibility schedules in addition to the above problems. Here's a chart illustrating how benefits per child for a typical tax unit family change as their income increases — the very poor get nothing, the near-poor get a whole lot, the middle class gets a modest amount, and then it flattens out for all but the very rich.

[Courtesy People's Policy Project]

It would be simpler, cleaner, and more fair for the government to simply give all parents a monthly check for each child automatically. That would be easy (no application required), include all parents, and permanently help all families in the future. Bruenig suggests $374 per month, which would slash child poverty by roughly two-thirds. Then some of the cost could be compensated for by scrapping the CTC and the EITC (except for the small part for non-parents, which Biden would increase), and modestly raising taxes on the rich.

People often get tangled up about including the rich in a universal program, but the smart way to make sure they aren't unduly benefiting from the program is to raise their overall taxes. That way we don't have to fuss with means testing bureaucracy, and all parents will rest easy knowing the checks will come even if they lose their jobs.

And finally, it's not going to be that much harder to pass a permanent child allowance than it is to do Biden's plan. It would only be a modest increase to the cost of the current bill, and would achieve a major goal of helping families that Democrats have been promising to do for decades. If we're going to do it, we might as well do it right!

If Biden did actually get a child allowance through, he would instantly have the best record on poverty of any president since Lyndon Johnson, and would take his place as one of the better presidents in history. Moreover, as we've learned over the last year, people really, really like getting checks from the government, especially when they don't have to do anything to claim them. The parents of the 75 million children in America are likely to show their appreciation at the ballot box in 2022, and Democrats might be able to hang on to their congressional majorities.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.