The COVID vaccine pipeline

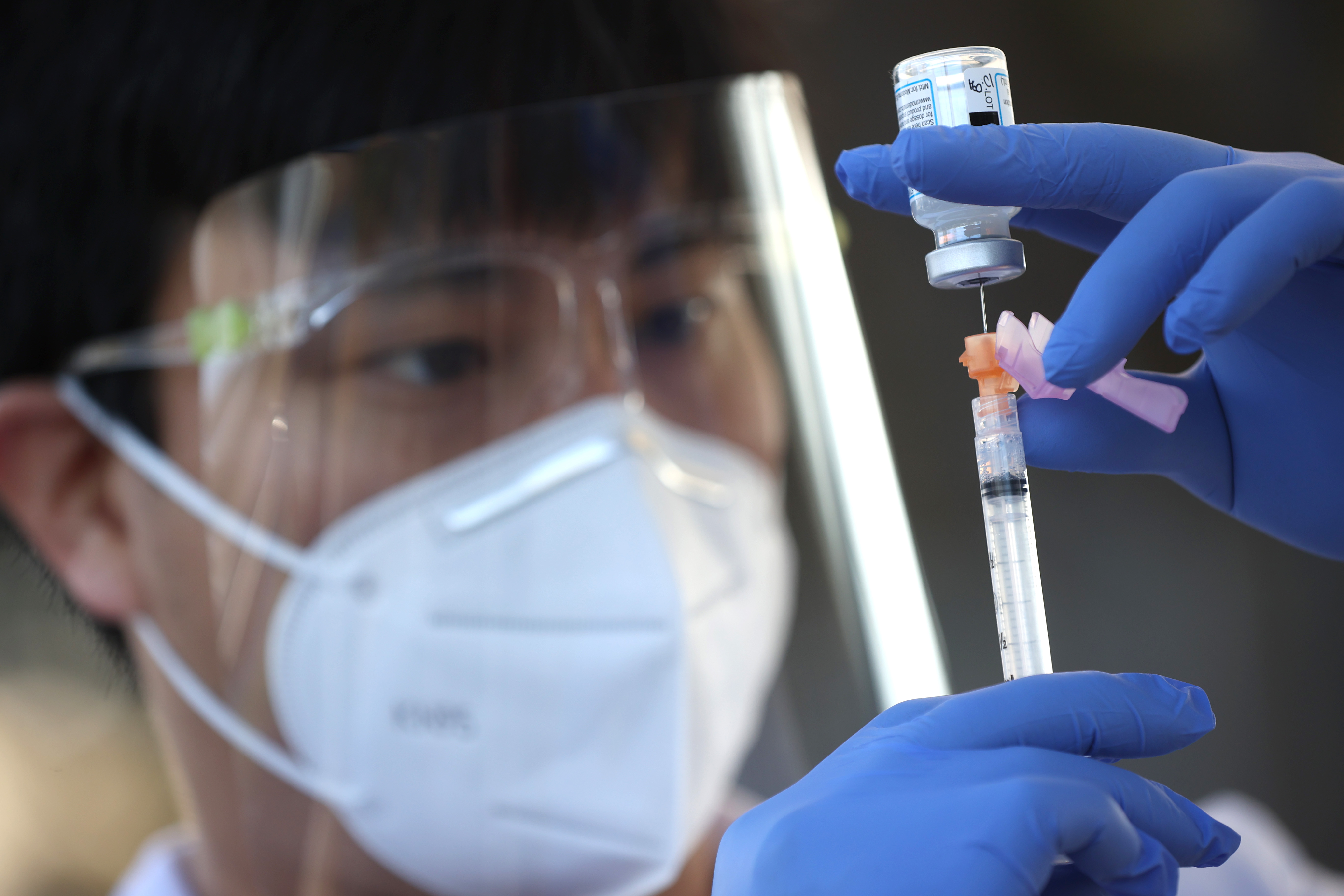

Pharma firms are racing to produce billions of coronavirus shots. Can they deliver?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pharma firms are racing to produce billions of coronavirus shots. Can they deliver? Here's everything you need to know:

What's the production target?

To fulfill President Biden's goal of having enough COVID-19 vaccine for all 260 million American adults by June, Pfizer and Moderna must each deliver 200 million doses of their two-shot vaccines by that deadline. So far, the federal government has received and distributed about 110 million doses. Johnson & Johnson has pledged to deliver 87 million doses of its one-shot vaccine by the end of May. But shortly before receiving FDA authorization for its shot in late February, J&J revealed it would ship 17 million fewer doses this month than planned. Factories in Kalamazoo, Michigan; Bloomington, Indiana; and Baltimore are producing the new vaccines at a speed that has never been seen before in the history of pharmaceutical manufacturing, and a record 2 million jabs are now being administered in the U.S. each day. But with some 1,700 Americans dying daily of COVID — and vaccine orders pending from foreign countries for billions of doses — pharma firms are under enormous pressure to speed up and overcome production bottlenecks across an incredibly intricate supply chain. "The big problem," said Georgetown University global health law professor Lawrence Gostin, is "how do you get a company that is already producing at maximum capacity to go beyond that?"

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How are the vaccines made?

The pipeline for Pfizer's innovative shot starts in St. Louis, where bacterial cells embedded with the DNA blueprint for the coronavirus' spike protein grow in massive steel vats. After about four days, scientists break open the cells and strain out the DNA, which is frozen and shipped — sometimes on Pfizer's company jet or helicopter — to Andover, Mass. That DNA is then incubated with genetic building blocks to create messenger RNA, which when injected into the human body teaches cells to build replicas of the spike proteins, which in turn teach the immune system to recognize the real thing. Next, frozen mRNA is transported to the 2,000-acre campus in Kalamazoo. There, it is used to make the bulk vaccine, which is put in vials, capped, inspected, labeled, and shipped. The mRNA in Moderna's shot is made in Norwood, Massachusetts, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, then packaged in Bloomington, where five shifts of 2,000 employees keep the assembly line running 24/7.

What about Johnson & Johnson?

Its vaccine uses a more traditional approach, employing a harmless cold virus to deliver DNA instructions for fighting the coronavirus. The two-month process of fermenting J&J's vaccine is supposed to take place at a Baltimore plant run by a partner firm, Emergent, which received $628 million from the Trump administration to expand production capacity. However, Emergent has still not received FDA approval to make J&J's vaccine; that is expected to happen in the coming weeks. Because of those delays, J&J's first 4 million doses were produced in the Netherlands. The firm is receiving logistical support from the Defense Department and says it is on course to deliver 100 million doses by the summer. "This is not making corn flakes," said Sean Kirk, Emergent's executive vice president of manufacturing. "It's something that cannot be rushed."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are there enough raw materials?

Pfizer and Moderna need more lipids, the fatty nanoparticles that encase their fragile mRNA molecules. The FDA approved lipids as a drug-delivery system only three years ago, as part of a treatment for a genetic disease that affects some 50,000 people worldwide. Unsurprisingly, the pharma industry was in no way prepared to suddenly supply nanoparticles for billions of COVID shots. Pfizer and Moderna are sourcing the material from the few companies in the U.S. and Europe that produce lipids, and are helping those firms scale up the complex manufacturing process. Both the Trump and Biden administrations invoked the Defense Production Act to give Pfizer and Moderna priority for lipids, and also used the Korean War–era law to address a shortage of glass vials needed to hold the finished vaccines.

What else is the federal government doing?

The Biden administration has helped factories secure much-needed machinery, tubing, and filtration systems. Officials have also scoured the country for additional manufacturing capacity and last week brokered a historic deal under which the government will pay pharma giant Merck $269 million to devote two of its facilities to producing Johnson & Johnson's vaccine. "This is the type of collaboration between companies we saw in World War II," said Biden. One Merck location will ferment the vaccine, potentially doubling supply, and the other will provide "fill-finish" services. Setting up those facilities will take several months, but could aid with the production of booster shots that might be needed to tackle variants later this year.

Are other firms collaborating?

Yes, but it's not as simple as "giving a recipe to another restaurant," said John Grabenstein of the Immunization Action Coalition. "That 'recipe' is thousands of pages long." Each facility that works on a component of a vaccine needs regulatory approval to perform that specific function. Despite these hurdles, Pfizer has struck deals with 10 partners worldwide, including French giant Sanofi and Swiss firm Novartis. Sanofi will also help J&J fill vials in Europe. Those working day and night at vaccine factories know the importance of their work. "It's a dream project," said Chaz Calitri, who leads the vaccine program at Pfizer's Kalamazoo plant. "But at the same time, it's the weight of the world."

Calling all vaccinators

With a steadily rising number of vaccine doses being shipped each week, many states are now reporting a different kind of shortage: people to give shots. Volunteer vaccinators must be current or retired medical professionals and the training requirements vary by state — even those skilled in giving jabs sometimes have to take online refresher courses that can last six hours. To fill out the workforce, some states are recruiting dentists, pharmacy interns, paramedics, medical students, and trainee nurses. The Pentagon has also deployed more than 1,000 active-duty service members to help staff Federal Emergency Management Agency mass-vaccination sites. Katie Croft-Walsh, a 65-year-old lawyer who'd previously worked as a registered nurse, recently volunteered at a vaccination center in San Antonio. The patients receiving jabs were "very kind and nice," she says. "It made me remember why I went into nursing in the first place."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more