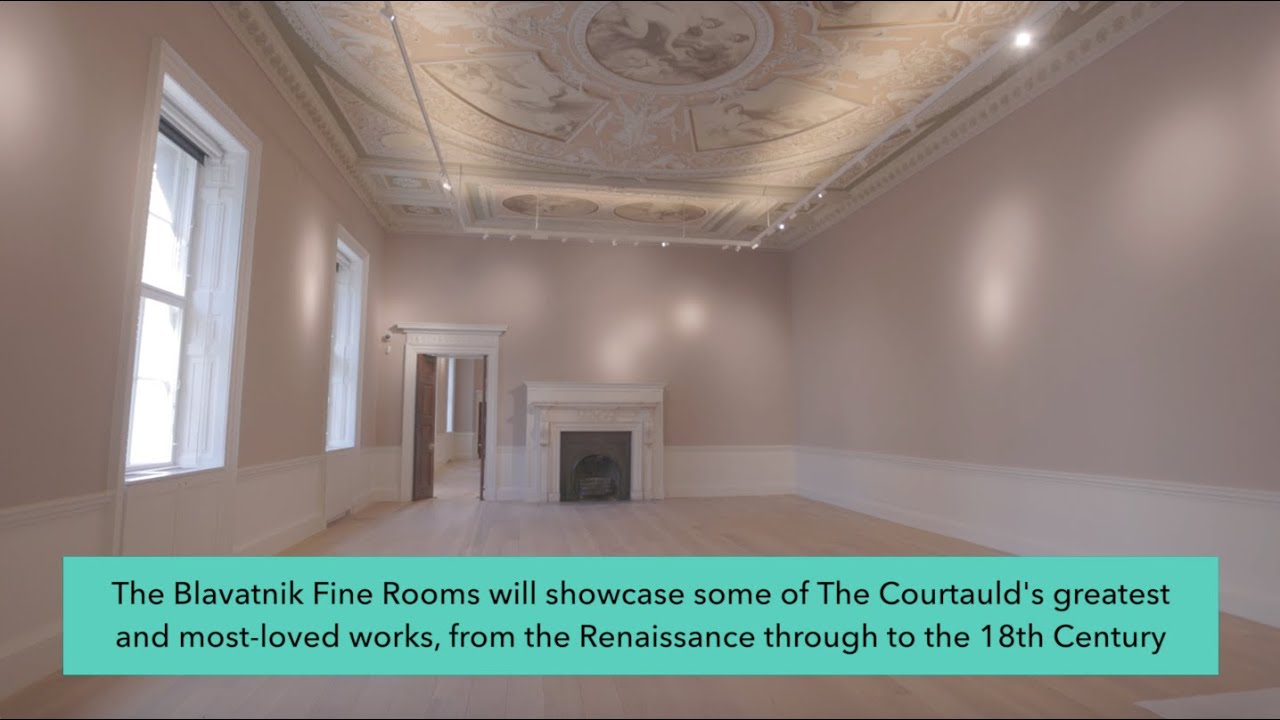

Courtauld Gallery reopening: Somerset House museum ‘looking better than ever’

Gallery now open to the public after closing in 2018 for a £57m refurbishment

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“When the Courtauld Gallery closed in 2018 for renovation, I feared it might lose the atmosphere that made it one of the most unique London museums,” said Ben Luke in the London Evening Standard. “But it’s looking better than ever, with a perfectly judged renovation.”

This remarkable collection, established by the textile magnate Samuel Courtauld and his wife Elizabeth in 1932 and displayed in Somerset House, groans with masterpieces – paintings by the likes of Bruegel, Botticelli and Rubens, as well as one of the most spectacular troves of impressionist and postimpressionist art in the world.

Yet for all its charms, the Courtauld did not always show its art “in the best way”: the pictures were hung clumsily, the gallery layout was awkward and it was a “nightmare” for people with disabilities.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, thanks to a £57m refurbishment, that has all changed. The renovations have opened up what were once cluttered spaces into a coherent whole, while the lighting and decor have been made dramatically more sympathetic to the paintings. And what paintings they are: from magnificent medieval and early Islamic works to van Gogh’s Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), and “superb” pieces by modern masters including Cy Twombly and Philip Guston, it offers “one jaw-dropping moment after another”.

Reacquainting oneself with the treasures of the Courtauld is almost “too much”, said Adrian Searle in The Guardian. “Surprises at every turn keep you alert and keep you looking”, whether at a “slightly mad” 1550 portrait of an English Naval officer or at Cezanne’s The Card Players (1892-1896); at the “hall of mirrors and reflections” in Manet’s epochal A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) or at Cranach’s Adam and Eve (1526). You’re constantly reminded of the collection’s impressive “historical sweep and variety”.

The refurb itself has been carried out with the utmost subtlety, said Rowan Moore in The Observer. Indeed, it’s so subtle that at times it’s hard to see quite what all those millions actually bought. There are, though, occasional slips: the staircases have been fitted with “crude white rectangular light fittings” of the sort you might find in “a cheap hotel”, while the gallery’s glorious medieval works of art are “consigned to a cramped and low-ceilinged room”.

Much of the old Courtauld’s idiosyncratic charm has been sacrificed, making it feel much more like an ordinary museum, said Waldemar Januszczak in The Sunday Times. But the new, broadly chronological hang is easier to follow: some masterpieces that were previously hidden away are given “pride of place”, such as Botticelli’s “great altarpiece” The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalen and John the Baptist.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Elsewhere, two dozen Rubens paintings that were once scattered piecemeal throughout the galleries are given a well-deserved room to themselves. Best of all is the new impressionist and postimpressionist gallery, where we get “a wall full of superb Cézannes”; a selection of some fine Gauguins, including the “haunting” Nevermore (1897); “exceptional” Seurats; and “heartbreaking” van Goghs.

It may not be perfect, but the Courtauld’s makeover is “unquestionably a success”. This well-kept secret is now likely to become a major tourist attraction. “So, yes, a lot has been gained. But a little has also been lost.”

Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, London WC2 (020-3947 7777, courtauld.ac.uk). Now open to the public

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

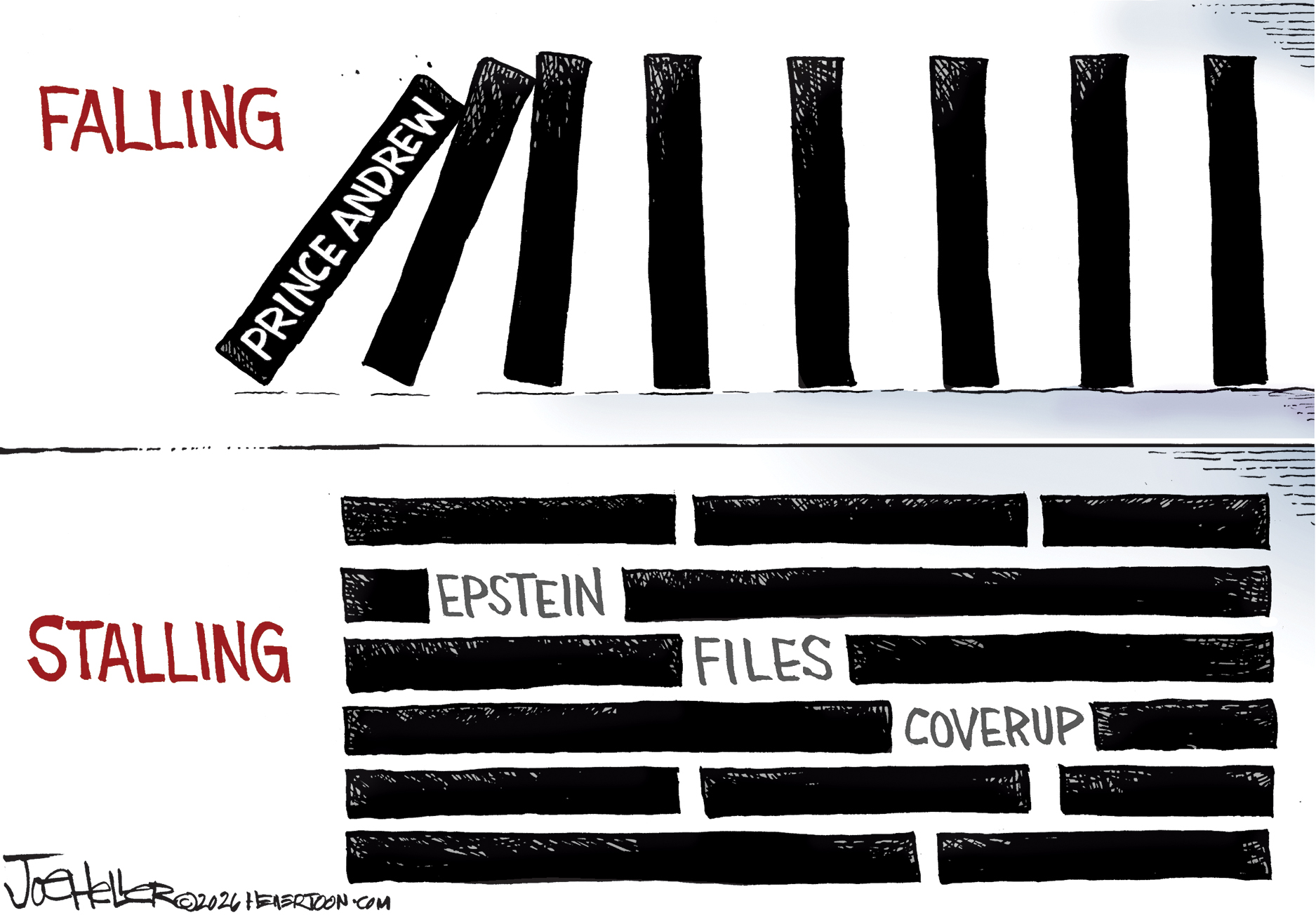

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts