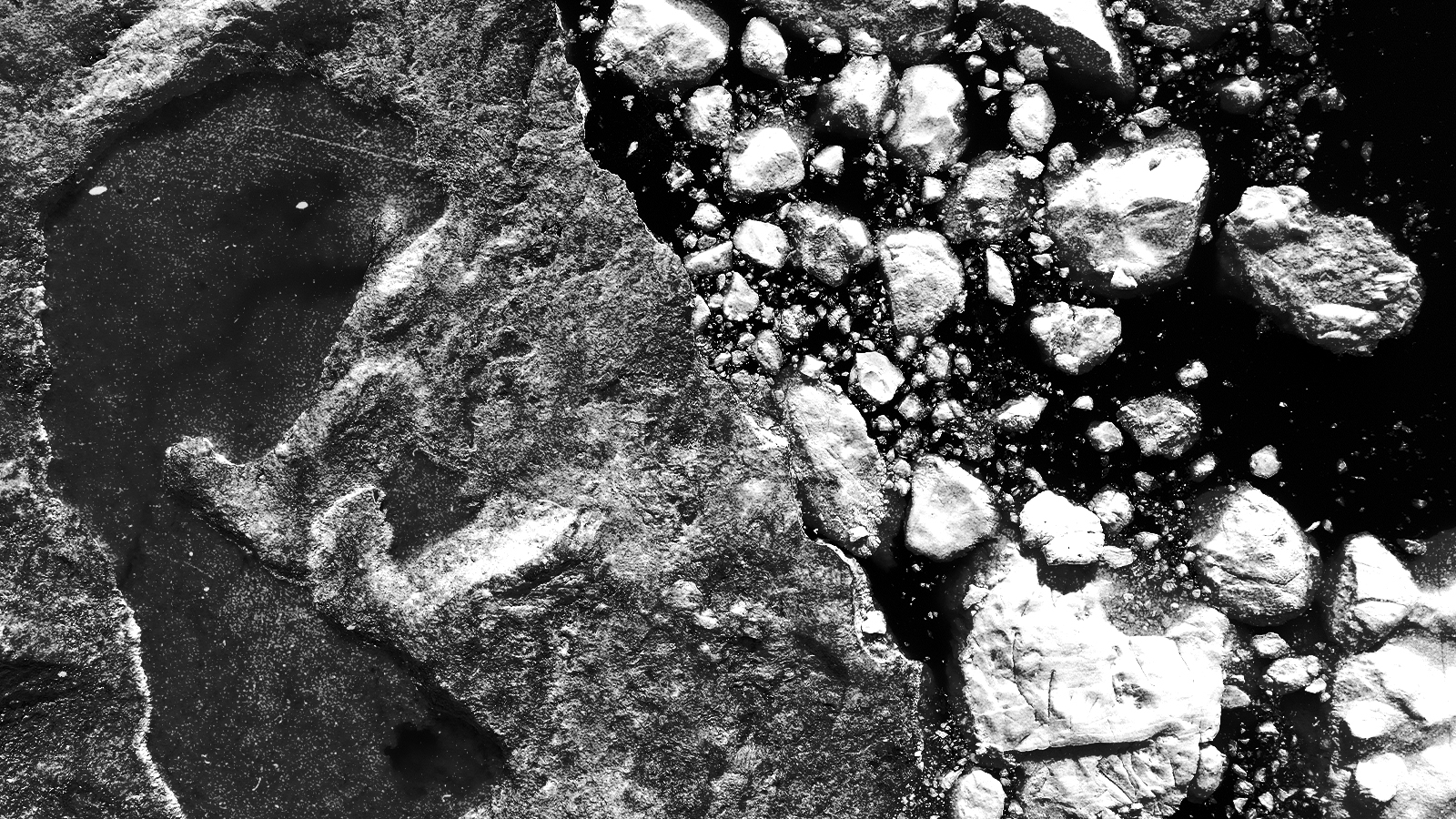

'Zombie ice' is real — and it's as spooky as it sounds

A scary new report says climate change will have massive effects on our oceans and coasts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Zombie ice" might sound like a concept out of a 1950s B movie, but it's a real thing — and it's dangerous. Scientists said this week that zombie ice from Greenland's melting ice sheet will raise global sea levels by an average of 10 inches.

Climate change is the culprit, of course. And the impact of that melting ice will be unexpectedly huge.

"The unavoidable 10 inches in the study is more than twice as much sea level rise as scientists had previously expected from the melting of Greenland's ice sheet," The Associated Press reports. A 2021 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, had previously estimated that Greenland would be responsible for up to five inches of rising water globally. Can anything be done about the attack of the zombie ice? Here's everything you need to know:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is zombie ice?

"It's dead ice. It's just going to melt and disappear from the ice sheet," said William Colgan, a glaciologist who co-authored the new study. Here's how that works: In the pre-climate change times, snowfall in Greenland was expected to refresh and thicken the sides of the country's glaciers, AP reports. "But in the last few decades, there's less replenishment and more melting, creating imbalance." The so-called "zombie ice" is ice that still exists but is "no longer getting replenished by parent glaciers now receiving less snow." And soon enough, much of it will simply melt.

Of course, it's not news that Greenland's ice sheet — the second-biggest in the world, after Antarctica — is melting quickly. Scientists from Ohio State University in 2020 reported that the country's snowfall was no longer keeping up with the ice melt — which meant that the ice sheet would keep melting even if global temperatures stopped rising, or even started to cool. That latter scenario obviously hasn't happened. Continued rising temperatures mean that glaciers are now sitting in pools of ever deeper water that accelerate their melting process: "Warm ocean water melts glacier ice," the Ohio State scientists said, "and also makes it difficult for the glaciers to grow back to their previous positions."

Long story short? The Greenland ice sheet has long since passed "the point of no return."

What effects will a rising ocean have?

"Sea level rise poses a serious threat to coastal life around the world," National Geographic says in an explainer on the topic. The ramifications will include intense storm surges, flooding, and damage to wildlife habitats across the coasts. And this isn't just a future problem: In Florida, for example, ocean levels are eight inches higher than they were in 1950. That creates all kinds of issues. Drinking water is threatened because the rising seas have "allowed saltwater to intrude into the drinking water and compromised sewage plants," says SeaLevelRise.org, and "there are already 120,000 properties at risk from frequent tidal flooding in Florida." That forces property owners to retreat from the coasts — unless state and federal governments spend billions on infrastructure projects designed to keep the seawater at bay.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But it's not just homeowners who will suffer. More than 40 percent of the U.S. population — 133 million people as of 2013 — lives and works along the American coasts, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. That's just America. Globally, "some of the latest estimates suggest that as many as 630 million people may live on land below projected annual flood levels by the end of the century," The Conversation reported in 2020.

Is there any way to stop this?

Not really. A lot of the damage has already been done. The Associated Press points out that the new study predicts that 3.3 of Greenland's ice sheet will melt "no matter what" even if everybody in the world started driving electric cars tomorrow. And the study only estimates the effects of Greenland's ice melt — it doesn't include the likely effects of climate change in Antarctica and other ice-bound environments.

This is usually the part of the story where we're supposed to offer a little hope, but the researchers don't have much to supply. "Even if the whole world stopped burning fossil fuels today, the Greenland Ice Sheet would still lose about 110 trillion tons of ice," say the study's authors, researchers at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. Even scarier, they say their estimate of a 10-inch sea rise from Greenland's ice sheets "is a very conservative rock-bottom minimum."

"Realistically," said Jason Box, one of the co-authors, "we will see this figure more than double within this century."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures