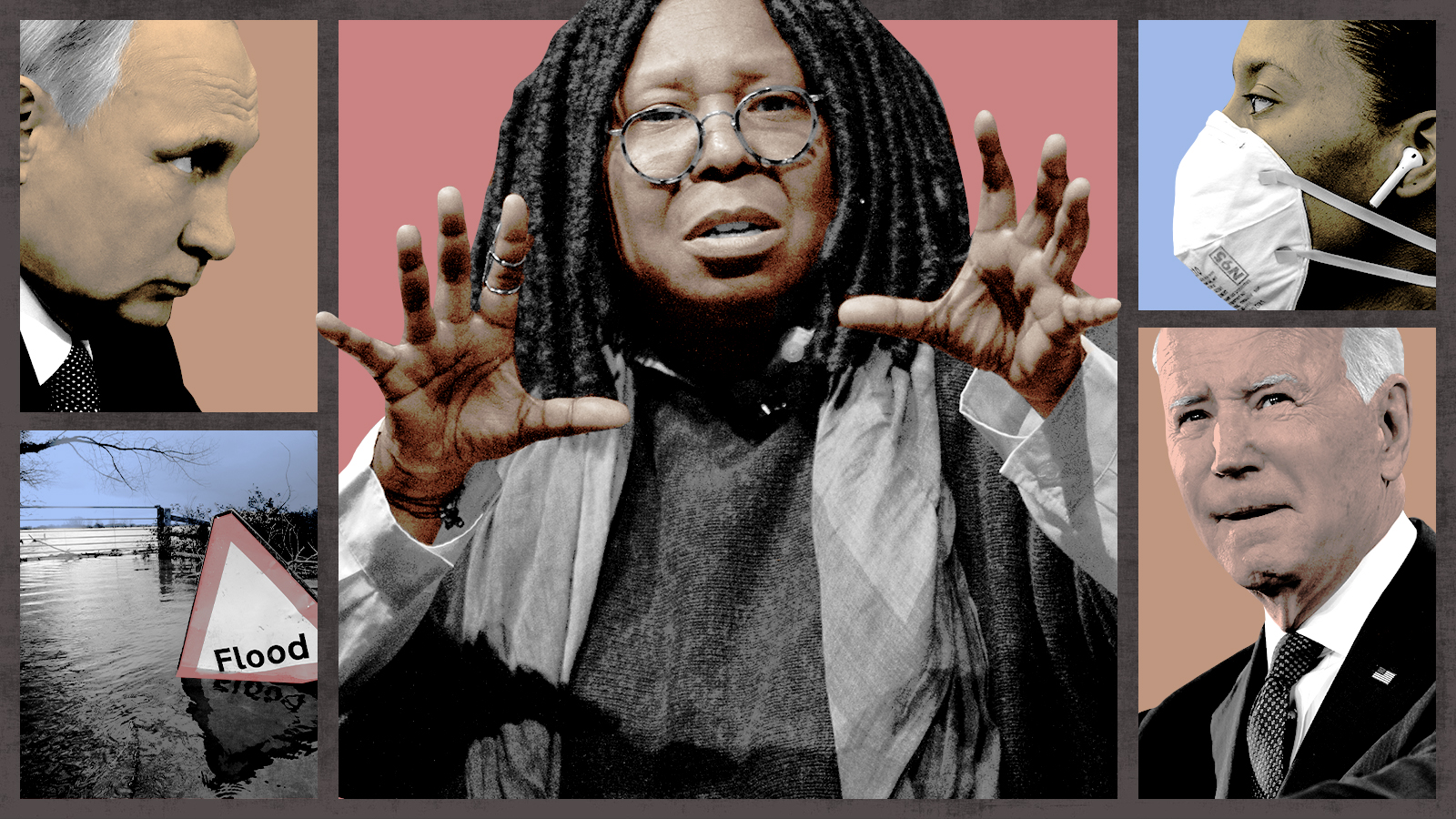

We used to be a proper country. Now we argue about Whoopi Goldberg.

How Americans lost even a vestigial capacity for seriousness about real problems

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A curious meme has been making the rounds on social media over the last few months. Easier to recognize than to describe, it revolves around photos of iconic yet antiquated settings of the American Century, like video stores, or chain restaurants that cater to families. Along with the image goes the caption: "We used to be a country. A proper country."

Following the usual pattern on Twitter, apparently unironic uses of the meme were quickly replaced by snark. Wits replaced department stores and hamburger dinners with pictures of tacky furniture or ads for schlock movies. The point — more implied than stated — was that idealizing the waning decades of the 20th century is, at best, ridiculous and, at worst, dangerously reactionary.

The past is never so appealing as our recollections. But recently I've been wondering whether the "proper country" meme might be onto something. It's not that I miss the fashions or food courts of my 1990s youth. But it often seems as if Americans have lost even a vestigial capacity for getting serious about real problems.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Take the controversy over Whoopi Goldberg's historical opinions. The only way to explain the matter to someone not already steeped cable news and social media would be that a minor celebrity who appears on a daytime television show watched largely by senior citizens said a very stupid thing about the Holocaust. One might add that the comments were part of a discussion of the decision by a local school board in an obscure corner of Tennessee not to require 8th graders to read the graphic novel Maus. There are plausible objections to both incidents. But the grounds for outrage seem minimal compared to the looming threat of war in some of the very areas devastated by World War II.

Or consider the ongoing spat about Joe Rogan's podcast. Once again, imagine trying to explain to a time traveler why the choice of guests by a former reality show host and fight sports commentator is national news. Rogan's $100 million contract is at stake, as well as more general concerns about media companies' legal responsibilities for content they host, unofficial censorship, and the danger of magnifying crank opinions. But these are hardly the most pressing challenges of our time.

It's not as if anyone is compelled to follow such non-stories, of course. And there's plenty of reporting and debate about genuine issues — if you care to find it. But it's hard to avoid wondering whether these things would get considerably less attention in a "proper country." The same goes, only more so, for Rudy Giuliani's appearance on something called The Masked Singer.

Some causes of our flight away from reality and into the staged, low-stakes conflict of reality shows are fairly recent. They include the shift of the media business from supplying advertisers with a broad yet stable audience to pursuing the momentary attention of a smaller number of heavy users. Cultural provocations drive traffic. Quick takes also cheap to produce, since they requires neither expertise nor time to write about them. Although I try to resist these incentives, I can't claim that I've always been successful. And I have the security of a day job that doesn't require me to generate clicks.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's not all about economic pressures, though. More than three decades ago, the sociologist Neil Postman argued that the form of public discourse determines its content. Even when used with the best intentions, some media impose inherent limitations on the sophistication and variety of ideas they can express.

Writing in the 1980s, which is now the object of nostalgia, Postman worried that television simply could not accommodate the subtlety of a literary text. Although social media have revived the written word in certain ways, postliterate communication also tends to compress and degrade the possibilities of expression from developing a rational argument to signaling a particular attitude. That's why memes like "proper country" circulate more quickly and widely than extended articles.

Beyond economic and formal causes, though, I wonder whether the prominence of fake news and junk commentary is a reaction to the sense of powerless that pervades American life.

Faced with the pandemic, inflation, rising crime, plus (according to political inclination) family breakdown, climate change, a looming social credit system, and the risk of a serious constitutional crisis, it's tempting to avoid things we can't control and concentrate on those it seems we can. Rather than an assertion of strength, so-called cancel culture is a largely expression of weakness. If we can't save the world or our country, we can at least demand that people be fired for whatever we consider asinine, offensive, or otherwise obnoxious opinions.

As Postman's argument indicates, there's nothing new about fears that Americans have lost the capacity to address or even to perceive the truth about ourselves and our condition. At different times, TV, comic books, movies, and popular music have all been blamed for making us trivial, dumb, and ineffectual. Yet somehow we muddled through the challenges of the 20th century.

Still, the repetition of a charge doesn't mean it's false. We used to be a proper country. Or did we?

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?Talking Point The latest slew of embarrassing emails from Fergie to the notorious sex offender have put her daughters in a deeply uncomfortable position

-

Australia’s teens brace for social media ban

Australia’s teens brace for social media banIn The Spotlight Under-16s will be banned from having accounts on major platforms

-

'Are We Dating the Same Guy?': do Facebook groups harm or help?

'Are We Dating the Same Guy?': do Facebook groups harm or help?Talking Point Women share their relationship experiences to try to stay safe on dating apps but critics highlight legal and emotional issues

-

How false notions of moral autonomy scrambled American parenting

How false notions of moral autonomy scrambled American parentingopinion American parents are great at keeping our kids' bodies safe. But what about their minds?

-

Standing 'sentinel' on social media won't fix Ukraine

Standing 'sentinel' on social media won't fix UkraineTalking Point

-

Late night hosts have questions, suggestions for Facebook's big 'metaverse' rebrand

Late night hosts have questions, suggestions for Facebook's big 'metaverse' rebrandSpeed Read

-

John Oliver tackles viral misinformation in immigrant communities, but also from his 'business daddy' AT&T

John Oliver tackles viral misinformation in immigrant communities, but also from his 'business daddy' AT&TSpeed Read

-

Senators cluelessly question whistleblower about Facebook in SNL cold open

Senators cluelessly question whistleblower about Facebook in SNL cold openSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts joke about how people survived the great Facebook-Instagram outage of 2021

Late night hosts joke about how people survived the great Facebook-Instagram outage of 2021Speed Read