The social psychology concept that could persuade the vaccine-hesitant

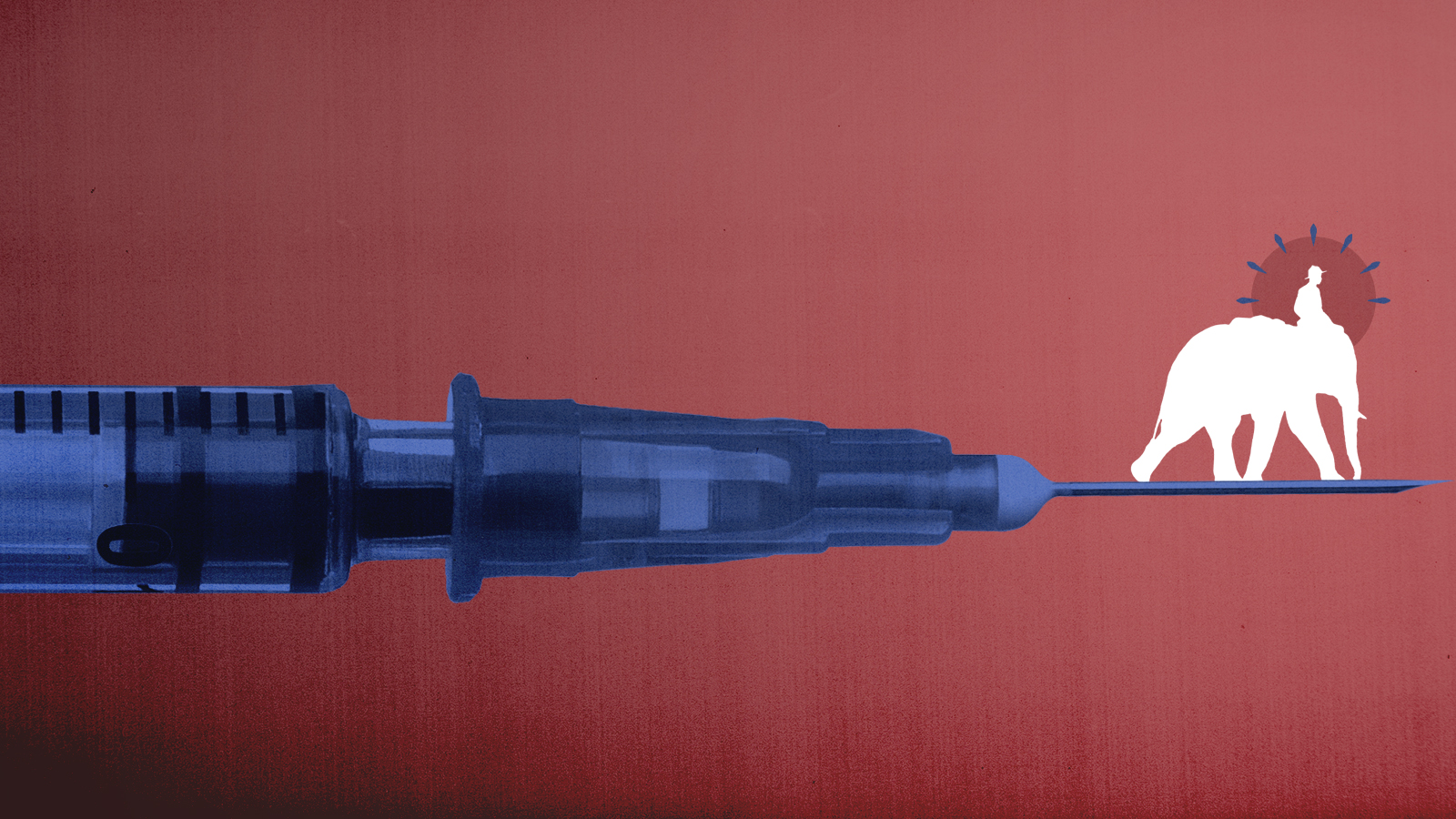

Vaccine campaigns must appeal to the elephant in the brain

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I am not the target audience for exuberant TikTok influencers hawking COVID-19 vaccines. For one thing, I'm long since vaccinated. For another thing, I am an adult.

That distaste is part of why my immediate reaction on seeing a TikTok clip making the rounds of political Twitter was dismissal. This stupid and futile, I thought. It will change precisely zero minds.

And there's a sense in which that's true. That video won't change minds, provided we're thinking of minds as the consciously reasoning part of us. Yet it might well change some people's decisions about vaccination — but not necessarily in the direction its creators hoped — because it appeals to the elephant of the brain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The idea of a brain elephant comes from a metaphor developed by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. Considering his own apparent irrationality and divided will, and drawing on millennia of human expression of the same self-experience, Haidt proposed our minds have two parts:

The image that I came up with for myself, as I marveled at my weakness, was that I was a rider on the back of an elephant. I'm holding the reins in my hands, and by pulling one way or the other I can tell the elephant to turn, to stop, or to go. I can direct things, but only when the elephant doesn't have desires of his own. When the elephant really wants to do something, I'm no match for him. [Jonathan Haidt in The Happiness Hypothesis]

That introduction might make it seem like the rider is our true self and the elephant somehow less human, more exterior, less us. But as Haidt further sketches the metaphor, he rejects that notion: "The rider is ... conscious, controlled thought," he explains. "The elephant, in contrast, is everything else. The elephant includes gut feelings, visceral reactions, emotions, and intuitions." Why, then, do we so often identify with the rider alone?

Because we can only see one little corner of the mind's vast operations, we are surprised when urges, wishes, and temptations emerge, seemingly from nowhere. We make pronouncements, vows, and resolutions, and then are surprised by our own powerlessness to carry them out. We sometimes fall into the view that we are fighting with our unconscious, our id, or our animal self. But really we are the whole thing. We are the rider, and we are the elephant. [Jonathan Haidt in The Happiness Hypothesis]

Many efforts to persuade people to get vaccinated against COVID-19 — some of mine included — have aimed much more at rider than elephant. Think statistics about vaccine safety, or explanations of the testing process, or analyses of comparative risks from the shots vs. the disease.

That stuff can work, but only if the elephant — one's gut, intuition, emotions — is already at least open to heading in that direction. For those whose elephant is walking (or stampeding) away from vaccination, all the statistics in the world won't be enough for the rider to turn things around. In most cases, the rider won't want to turn things around. My guess is that this far into vaccine distribution, most people still wary of getting a shot aren't lacking for statistics and risk analyses. Persuading them is an elephant problem, not a rider problem.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Let me be a little more precise about the group I have in mind. I'm not talking about those legally (i.e. children under 12) or medically ineligible for vaccination. Nor am I speaking of those who'd like to be vaccinated but face logistical impediments, like not being able to take enough time off work. I'm thinking about the one in three unvaccinated adults, per a new Kaiser Family Foundation poll, who still say they want to "wait and see" how the vaccines affect other people, as well as the one in four unvaccinated people who expect to get a shot by the end of 2021.

Unlike the 14 percent of American adults who have for nine months steadily insisted to Kaiser researchers they will "definitely not" get vaccinated, not this year or ever, these wait-and-see or maybe-later folks are persuadable. Their elephants aren't charging away from vaccination. They could be convinced to stop spectating and get the shot if their brain elephants can be moved in that direction.

Addressing the elephant instead of the rider doesn't mean no more statistics and reports — for scared elephants, reassuring numbers might help, while overconfident elephants can be shifted by worrisome hospitalization rates. It means more emotive, instinctive appeals, like linking the shots to favored public figures, be they President Biden or National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases chief Anthony Fauci or former President Donald Trump. Influencer campaigns, of which the White House alone has more than 50, fall into this category, too. They won't shift riders, but they may move elephants.

The challenge will be making sure the elephants move in the right direction. Take the TikTok clip I mentioned. Maybe it will be persuasive for some teenagers, who are one of the least-vaccinated demographics and seemingly the primary White House focus for influencer appeals. But videos like that and others from the Biden administration's "eclectic army of more than 50 Twitch streamers, YouTubers, TikTokers, and the 18-year-old pop star Olivia Rodrigo," will repel elephants, too.

The right-wing Daily Wire has already published a roundup of criticism of that clip, which its headline dubs "cringe and pathetic." That post includes a tweet from Donald Trump Jr., who's likely correct in his observation that given what we know about the demographics of adult vaccine hesitancy, the video may be counterproductive as it goes viral among the Very Online right.

However much we might prefer to imagine ourselves as all rider, the elephant isn't a bad thing. It's a good and necessary part of us. Yet it is undeniably difficult to direct.

We have to start moving more elephants to persuade the vaccine hesitant. We also have to make sure we steer them right.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Can foster care overhaul stop ‘exodus’ of carers?

Can foster care overhaul stop ‘exodus’ of carers?Today’s Big Question Government announces plans to modernise ‘broken’ system and recruit more carers, but fostering remains unevenly paid and highly stressful

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugees

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugeesSpeed Read The memo also ordered all green card applications for the refugees to be halted

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame game

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame gameFeature Kamala Harris’ new memoir reveals frustrations over Biden’s reelection bid and her time as vice president

-

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day