Coventry: how ‘Ghost Town’ transformed into 2021 City of Culture

Title winner was once Britain’s version of Detroit

Coventry was unveiled last week as the UKs next City of Culture, a milestone in the city’s decades-long battle to shed an image of post-industrial decline.

The scenes of despair there were formerly so bad that Coventry ska band The Specials were inspired to write their 1981 Thatcherite gloom anthem Ghost Town about the deterioration around them.

“I saw it develop from a boom town, my family doing very well, through to the collapse of the industry and the bottom falling out of family life,” the band’s drummer, John Bradbury, told the BBC in 2011.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The West Midlands metropolis beat rival bids from Paisley, Sunderland, Swansea and Stoke-on-Trent to secure the City of Culture designation, which will usher in a year-long programme of cultural events. Diversity and inclusivity will be at the heart of the project.

Coventry is hoping to emulate the experience of Hull, whose tenure as the title holder this year is “widely seen as a success”, not only attracting new investment but also providing a much-needed boost to regional self-esteem, says The Times.

“The hotels are full, the city centre is buzzing once again and the feeling of civic pride is almost tangible at every event,” Hull Daily Mail editor Angus Mail wrote in the Coventry Telegraph.

Britain’s Detroit

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Coventry famously took a pounding from Luftwaffe bombs during the Second World War - more than 1,400 people were killed or seriously injured in a single night, when 16,000 Nazi bombs were dropped on the city on 14 November 1940 - but quickly got back on its feet following the conflict thanks to the booming motor industry.

By the 1950s, Coventry was drawing comparisons to “motor city” Detroit, with a dozen locally based carmakers providing plentiful manufacturing jobs and competitive wages.

However, like its US counterpart, “as the car industry fell into decline, so did Coventry”, says The Guardian.

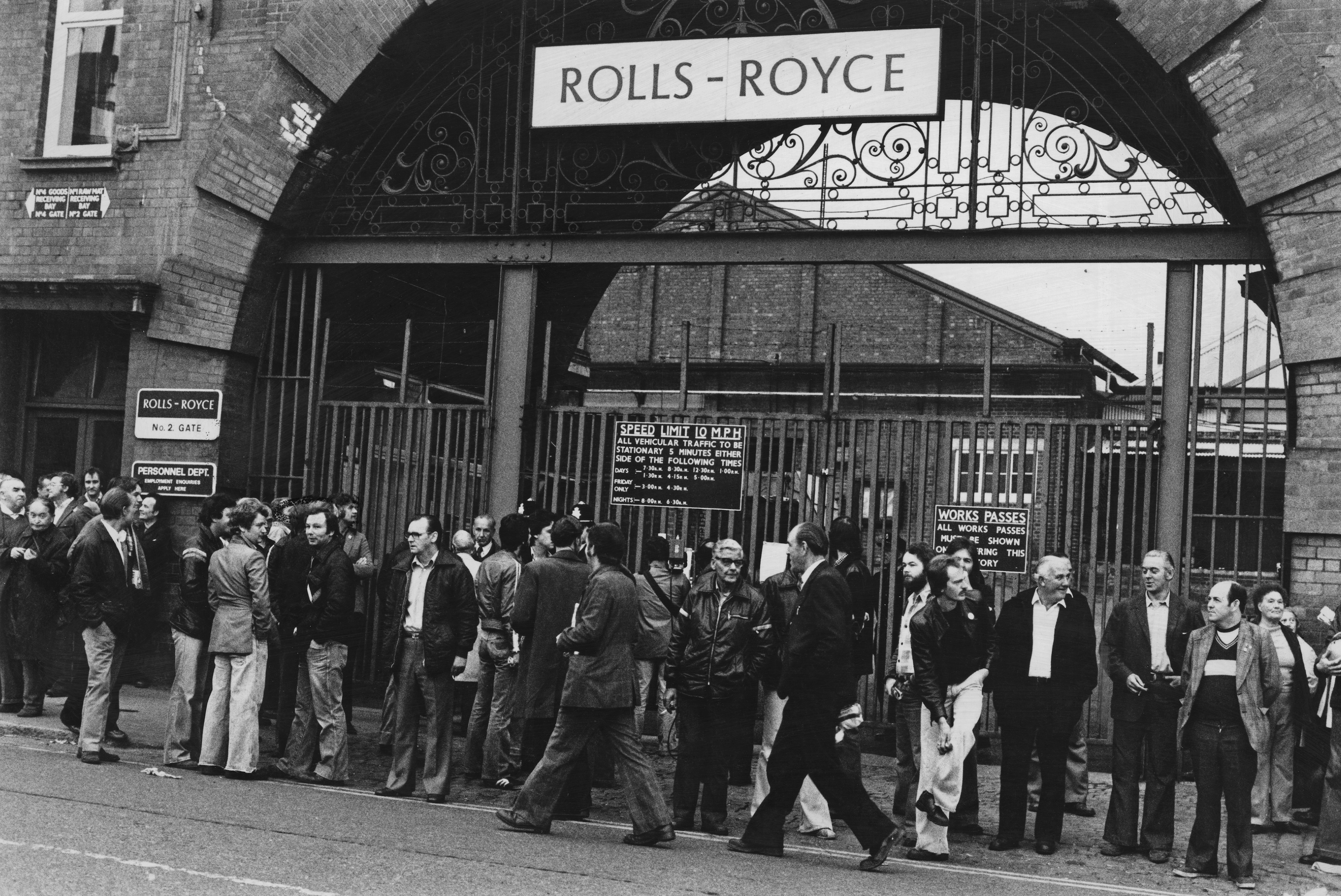

Between 1975 and 1982, the city’s top 15 employers laid off a combined total of almost half of their workforce as the UK automotive industry lost ground to competitors abroad.

Workers locked out of the Rolls Royce plant in Coventry during an industrial dispute in September 1979. (Aubrey Hart/Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

By the mid-1980s, unemployment stood at 17%, according to the BBC. Businesses closed their doors, buildings fell into disrepair and jobless young people left in droves to try their luck in London and the Southeast.

Bouncing back

Fast-forward to 2017 and the picture is very different.

Economic renewal has been at the heart of the transformation. A major part of the city’s economic bounceback has come from reinventing its relationship with the industry that once made it a boom town.

Since the last traditional manufacturing plants closed their doors for good in the 2000s, Coventry has “gradually emerged as a research and development (R&D) hub”, says The Guardian. Investment in the R&D sector has paid off as carmakers look for innovative ways to reduce carbon emissions and keep pace with new technologies.

The new hybrid London cab, which went into service on 5 December, was developed by the London Taxi Company’s Chinese owner, Geely, in a high-tech factory a few miles northeast of Coventry. The £300m plant, which opened in March 2017, has created 1,000 new jobs, a fifth of them in R&D, in what locals hope will be a 21st century resurgence of Coventry’s automotive past.

London Taxi Company workers polish a new TX4 London cab (Matt Cardy/Getty Images)

Coventry’s rise has also been helped by the recovery of Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) and by Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG), a partnership between Coventry manufacturers and the University of Warwick, The Guardian reports. Next year, a £150m National Automotive Innovation Centre for advanced research open its doors in the city.

JLR also has expansion plans worth almost £500m and is reportedly planning a major new car factory, “meaning mass production could return to Coventry for the first time in more than a decade”, The Guardian says.

Admittedly, there is still plenty left to do before Coventry’s improved fortunes are felt across all segments of the population.

Pockets of the city are still racked by deprivation, teenage pregnancy rates remain disproportionately high, and more than a quarter of children are being raised in low-income household, compared with a national average of 19.9%, according to council statistics.

However, there is no denying that Coventry has experienced an astonishing turnaround. From its 1980s peak of 17%, unemployment fell to 8% in 2012, and 3.4% in 2015.

In 2017, Coventry came eighth in consultancy firm PwC’s Good Cities for Growth index, an annual ranking of 42 UK cities based on factors including income, employment, health and housing.

Brain drain in reverse

The thriving education sector has also helped reverse the “brain drain” and create new jobs. Coventry University, established in 1992, is one of the fastest-growing universities in the UK. Despite its name, the University of Warwick is also based in Coventry, and the two universities collectively employ more than 10,500 people, according to council figures.

As of 2015, graduates starting work in Coventry can expect to make more than their peers in Oxford, Glasgow or Bristol, according to the Centre for Cities.

This new-found confidence is reflected in ambitious plans to regenerate the city’s business and shopping districts. A multimillion regeneration project is due to have been completed by the time City of Culture events kick off in January 2021.

For David Burbidge, who led the title bid, there is a sense that being named City of Culture represents the next step of Coventry’s reinvention, passing from rebuilding the economy into the realm of cultural and spiritual rejuvenation.

“There is a real appreciation that an enhanced cultural life can be the cornerstone of a rebirth of the city”, fostering an atmosphere conducive to “ambitious thinking” and “further integration of our diverse communities”, he wrote last year.

Andrew Dixon, who advised the city on its bid, agrees that an image revamp is long overdue.

“It’s 70 years since the cathedral was bombed, it’s 35 years since The Specials did Ghost Town, but nobody talks about Coventry now: the youth, the diversity, the modern city,” he told the Coventry Telegraph.

“We are going from Ghost Town to Host Town now.”

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion