Ishihara test: what is colour blindness, and how can you get tested?

Not everyone sees the world the way you do. Find out more about colour blindness, its science and its effects.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Colour blindness affects approximately one in 12 men and one in 200 women, which equates to 4.5 per cent of the population or around 2.7 million people in the UK, according to campaign group Colour Blind Awareness.

Colour vision deficiency, or CVD, is usually genetic, passed to the child from the mother, but it can also develop as a by-product of aging or medical conditions, such as diabetes.

It is caused by problems with the cone and rod cells in the iris of the eye. In people with CVD, rod cells or one of three types of cone cells does not function properly, and the eye cannot pick up certain wavelengths of light. People with the condition can normally see just as clearly as those with normal vision, but are unable to fully detect red, green or blue light. Those with normal vision, or trichromancy, are able to detect all three types of light, as all of their cone cells function properly. The condition of people affected by any form of CVD is called anomalous trichromancy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Do people with CVD see any colour?

Full colour blindness — seeing the world in complete black-and-white monochrome — is extremely rare, as is being unable to pick up blue light. The most common form of CVD is red-green colour-blindness, or protanomaly. Rather than simply mixing up red and green colours with each other, red-green colour-blind people mix up any colours that use red or green as a component. For example, a red-green colour-blind person would have trouble distinguishing a blue pen from a purple one, because they cannot pick up the red colour in the purple pen. Blue colour-blindness, or tritanomaly, is significantly rarer.

How do I know if I have CVD?

In some cases, spotting colour vision deficiency can be difficult, especially in children, who have been taught that, say, roses are red and trees are green, but have no conception of what actually sets those two colours apart. Normally, optometrists administer a colour perception test as a routine part of an eye examination, but you may need to request a test specifically. The most common test administered in a routine check is the Ishihara Plate test.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

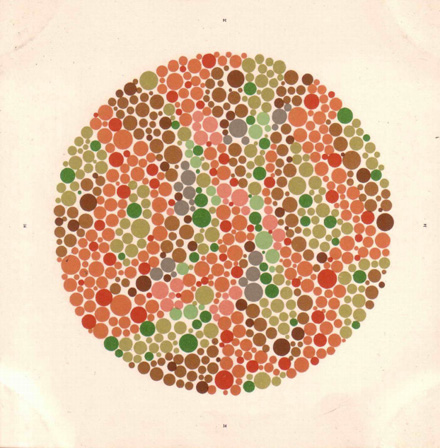

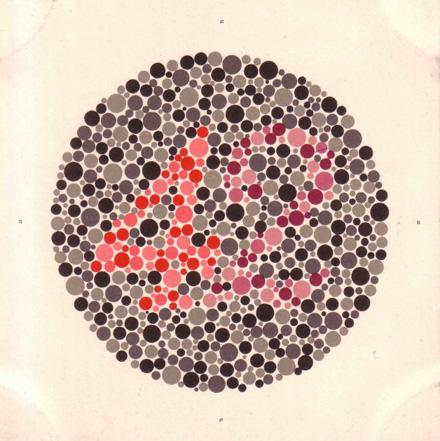

Dr Shinobu Ishihara developed the Ishihara test during World War II, when the Japanese government contracted him to develop a colour blindness test for new conscripts. The test involves 38 plates or images composed of coloured dots that have numbers 'hidden' in the patterns. The dots are laid out in such a way that a person with CVD will see a different number than a person with normal vision, according to Eye Magazine. For those unfamiliar with numbers, the Ishihara test includes plates that feature only squiggly lines, requiring those able to see them simply to trace what they saw. There is also a colour blind test for toddlers, which uses shapes instead of numbers provided that young children may not be able to read. Below are several examples of the plates used.

How accurate is the test?

Before examining the images below, note that this colour blindness test is simply a sample of the Ishihara test, and is not intended for diagnostic purposes. Computer screens vary and could change the exact colouring of the plates. The Ishihara Plate test can only signal red-green colour blindness — just because you can decipher the proper numbers on the Ishihara plates does not mean that you have completely normal vision. For any concerns, make an appointment with your optometrist.

Examples:

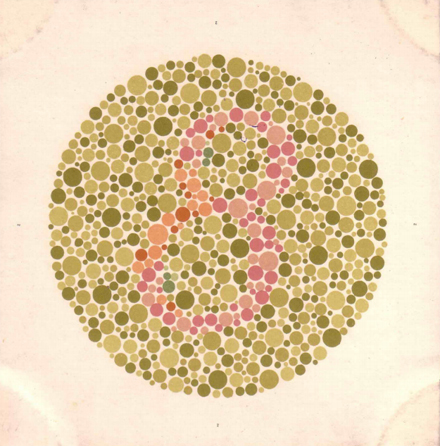

Question one (Plate 2 in the official test)

What did you see?

- 8 - People with normal colour vision should see an 8.

- 3 - People with red-green colour blindness will see a 3.

- Nothing - People with total colour blindness cannot read a numeral.

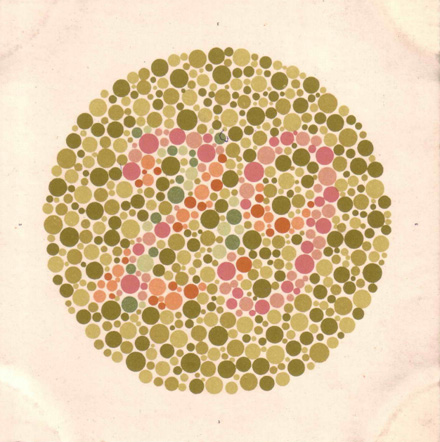

Question two (Plate 3 in the official test)

What did you see?

- 29 - People with normal colour vision see a 29.

- 70 - People with red-green colour blindness see a 70.

- Nothing - People with total colour blindness cannot read a numeral.

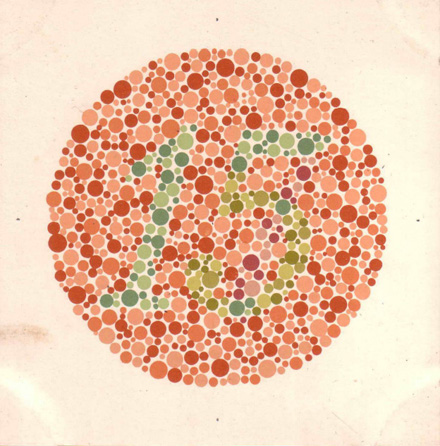

Question three (Plate 6 in the official test)

What did you see?

- 15 - People with normal colour vision see a 15.

- 17 - People with red green colour blindness see a 17.

- Nothing - People with total colour blindness cannot read a numeral.

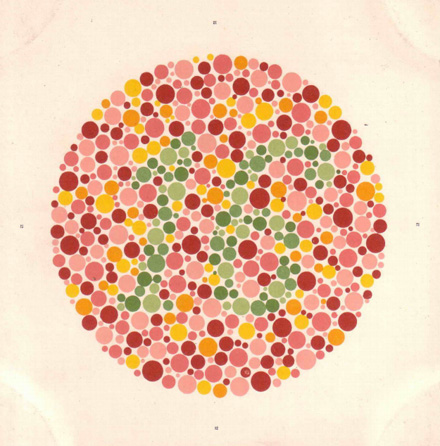

Question four (Plate 12 in the official test)

What did you see?

- 16 - Those with normal colour vision see a 16.

- Nothing - Most colour blind people will not be able to see a numeral clearly.

Question five (Plate 14 in the official test)

What did you see?

- Nothing - Both those people who have normal vision and people with total colour should not be able to see any numeral.

- 5 - Those with red green colour-blindness should see a 5.

Question six (Plate 17 in the official test)

What did you see?

- 42 - People with normal colour vision should see a 42.

- 2, faint 4 - People suffering from red colour blindness (protanopia) will see a 2. Those with mild red colour blindness (prontanomaly) may also see a faint number 4.

- 4, faint 2 - People suffering from green colour blindness (deuteranopia) will see a 4. Those with mild green colour blindness (deuteranomaly) may also see a faint number 2.

-

The year’s ‘it’ vegetable is a versatile, economical wonder

The year’s ‘it’ vegetable is a versatile, economical wonderthe week recommends How to think about thinking about cabbage

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restored

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restoredSpeed Read The Trump administration took down displays about slavery at the President’s House Site in Philadelphia