The pros and cons of streaming trials online

New rules mean more UK court cases will be shown online, allowing the public to watch proceedings

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The public can now watch some UK trials online under a new law designed to promote “open and transparent” justice.

The new rules will cover all courts and tribunals – from Crown and magistrates’ courts to family courts and immigration tribunals – and allow the public and press to observe hearings remotely via video link.

Anyone wanting to watch cases will have to identify themselves by their full name and email address, as well as agree to “conduct themselves appropriately”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The new law, introduced on Tuesday, “expands and makes permanent” temporary powers put in place during the Covid-19 pandemic to permit courts to hear cases by audio or video link to “reduce backlogs of cases”, said The Daily Telegraph.

According to guidance seen by the paper, judges must now “give due weight to the importance of open justice”.

“This is a mandatory consideration. Open justice serves the key functions of exposing the judicial process to public scrutiny, improving public understanding of the process, and enhancing public confidence in its integrity,” continues the guidance.

Judges will have the final say over whether proceedings are streamed and who can watch, but the guidance says remote viewing should be allowed if it is “in the interests of justice”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, judges will be able to disallow streaming in cases where it could block or jeopardise “the administration of justice”; for example, if it meant witnesses were unwilling to testify, or reporting restrictions were at risk of being breached.

The move is a significant step in a decades-old debate over whether cameras should be allowed in UK courtrooms.

1. Pro: increasing transparency

Proponents of streaming and televising trials say that it will bolster the legal principle of “open justice” and increase transparency around the judicial process. They also say it will increase trust and understanding in the sentencing system.

The new rules are an expansion of previous laws, introduced in 2020, which allowed TV cameras to film judges passing sentences in murder, sexual offences, terrorism and other serious high-profile criminal cases in Crown Courts in England and Wales, including the Old Bailey.

At the time, the BBC argued that the move was “a radical change and a significant extension to the operation of open justice”. The Lord Chief Justice, Lord Burnett, said at the time: “It is important that the justice system and what happens in our courts is as transparent as possible.

"My hope is that there will be regular broadcasting of the remarks in high profile cases, and that will improve public understanding.”

2. Con: risk of sensationalism

Opponents of the streaming or filming of trials often point to famous televised trials that have taken place abroad, such as that of OJ Simpson in 1994, or more recently, the 2014 trial of Oscar Pistorius.

Both became sensationalised media circuses, leading to accusations that justice was being turned into a form of entertainment. But top prosecutors have argued in the past that the workings of the British legal system are very different, and therefore not as likely to end up in the “free for all” seen in US trials.

When cameras were first allowed into the UK Court of Appeal in 2012, some feared it would lead to sensational US-style trials. But leading prosecutor Brian Altman QC, speaking to the BBC, said at the time: “One has to understand the process in America against a background of complete almost unfettered freedom and discretion”.

And it seems high-profile court cases in the UK where filming was already allowed – such as in the Supreme Court – do not attract large viewing figures.

The Supreme Court hearing for Julian Assange’s extradition to the US in February 2012 was watched by only 14,500 people, according to government documents – although public appetite for watching trials could have increased since then.

3. Pro: educating the public

The streaming of trials could lead to a better understanding of the sentencing system, thereby increasing confidence in the courts and judicial process.

That was part of the government’s argument when cameras were first allowed into the Court of Appeal in 2012. A government white paper, Swift and Sure Justice, said that the operation of the criminal justice system is “a mystery to victims and the public” and broadcasting what happens in court would help to “demystify” the process.

4. Con: risk of influencing juries

The ubiquitous use of social media and the rise of the internet means that streaming or televising trials could risk putting the jury at much greater risk of being influenced by public opinion.

This was a fear highlighted by Amber Heard’s lawyers ahead of the defamation trial brought against her by her former husband, the movie star Johnny Depp. Heard’s team unsuccessfully tried to exclude cameras from the trial, which took place in Virginia, where trial judges have “almost total discretion” over whether cameras are allowed into the courtroom, said Variety.

Heard’s lawyer, Elaine Bredehoft, argued ahead of the trial that there was already tremendous media attention as well as interest from “fearful anti-Amber networks” who would have access to the footage. “What they’ll do is take anything that’s unfavorable – a look,” Bredehoft said. “They’ll take out of context a statement, and play it over and over and over and over again.”

During the trial, Heard was at the receiving end of a significant amount of online vitriol. She told the court that she received “hundreds of death threats regularly if not daily, thousands since this trial has started, people mocking my testimony about being assaulted”.

5. Pro: research shows no negative impact

Cameras have been shown to have little to no effect on criminal proceedings, and in fact improve the administration of justice because the court is subject to greater public scrutiny.

Research conducted in 2000 on the impact of using cameras during UN International Criminal Tribunals found that court participants – which includes witnesses, lawyers and judges – are “not affected by cameras in court” and most felt that “cameras have a positive effect, or no effect, on the administration of justice”.

6. Con: risk to safety of victims and witnesses

Opponents argue that court participants could be recognised in public, which could lead to intimidation or jeopardise the safety of witnesses, lawyers and judges.

“If the public see judges’ faces in the living room on television and are able to identify them more readily then unfortunately they are more likely to be personally attacked, and possibly details published about them which should not be,” said Bar Council chairwoman Amanda Pinto QC when cameras were first introduced to England and Wales’s Crown Courts in 2020.

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How far does religious freedom go in prison? The Supreme Court will decide.

How far does religious freedom go in prison? The Supreme Court will decide.The Explainer The plaintiff was allegedly forced to cut his hair, which he kept long for religious reasons

-

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBI

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBIThe Explainer The case arose after the FBI admitted to raiding the wrong house in 2017

-

Supreme Court to weigh transgender care limits

Supreme Court to weigh transgender care limitsSpeed Read The case challenges a Tennessee law restricting care for trans minors

-

Supreme Court wary of state social media regulations

Supreme Court wary of state social media regulationsSpeed Read A majority of justices appeared skeptical that Texas and Florida were lawfully protecting the free speech rights of users

-

The pros and cons of a written constitution

The pros and cons of a written constitutionPros and Cons Clarity no substitute for flexibility, say defenders of Britain's unwritten rulebook

-

Judges allowed to use ChatGPT to write legal rulings

Judges allowed to use ChatGPT to write legal rulingsSpeed Read New guidance says AI useful for summarising text but must not be used to conduct research or legal analysis

-

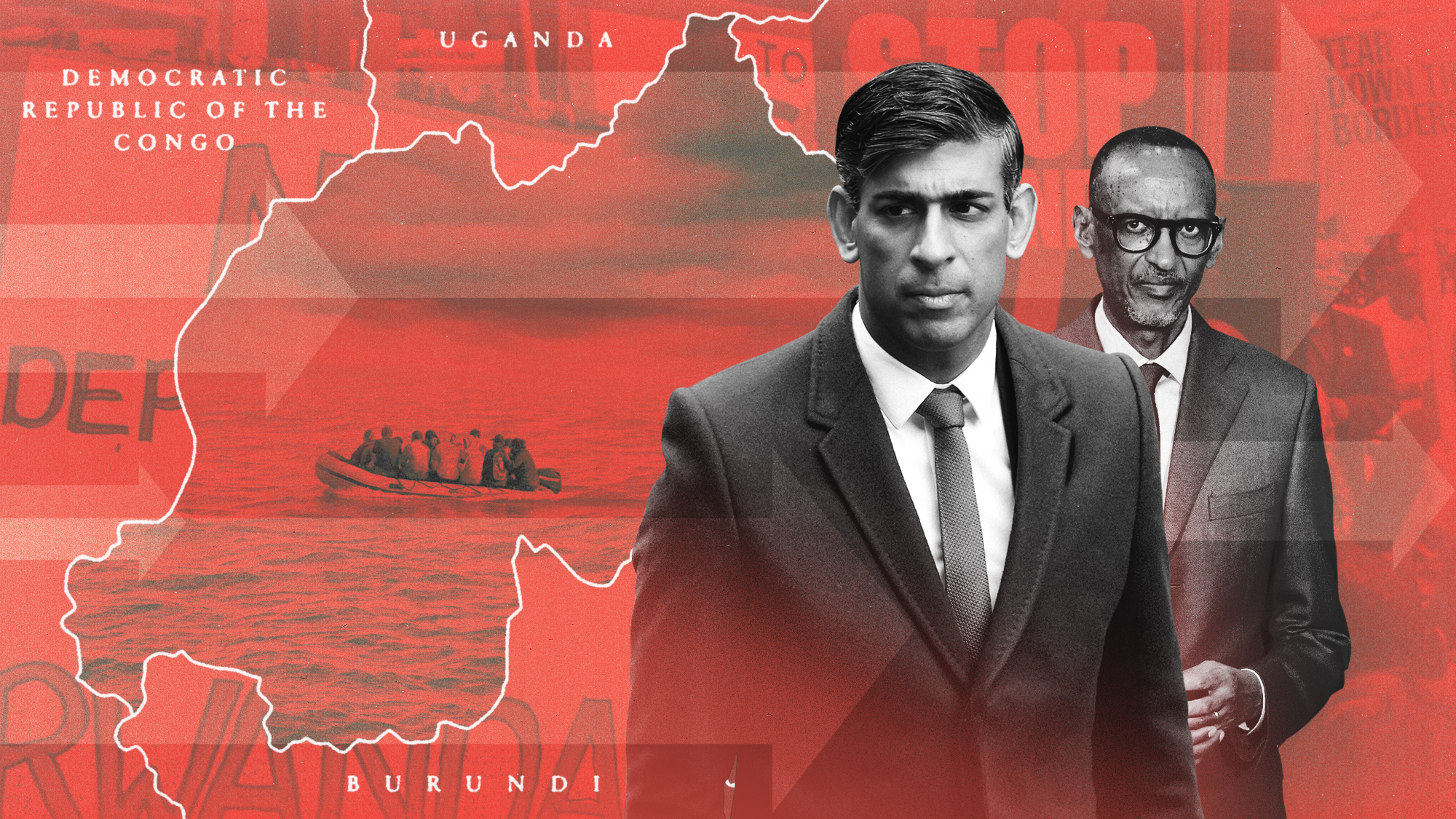

Pros and cons of the Rwanda deportation policy

Pros and cons of the Rwanda deportation policyPros and Cons Supporters claim it acts as a deterrent but others say it is illegal and not value for money

-

Is the Comstock Act back from the dead?

Is the Comstock Act back from the dead?Speed Read How a 19th-century law may end access to the abortion pill