Tunisia: the nail in the coffin of the Arab Spring

The country’s problems began with the election of Kais Saied as president, say his critics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tunisia was once the great hope of the Arab Spring, the sole democracy to emerge from the uprisings that swept North Africa in 2011. But the days of it being the showcase of the Arab world are gone, said Le Monde (Paris); with each passing week, the nation’s image is stained a little more.

The problems began with the election of Kais Saied as president in 2019. Within three years he had suspended parliament, and much of the constitution drawn up in 2014, and concentrated power in his own hands.

His repressive policies have been matched by increasingly xenophobic rhetoric that culminated in a speech last month in which he raged about “hordes” of migrants arriving in Tunisia from sub-Saharan Africa, bringing with them “violence, crimes and unacceptable practices”, and conspiring to alter radically the demographics of a proud nation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As a result of its slave trade (abolished in 1846), Tunisia has a sizeable black minority (about 10% to 15% of the population), said Lisa Bryant on VOA (Washington). And it was also the first country in North Africa and the Middle East to have criminalised racial discrimination (with a law passed in 2018).

But Saied’s speech was targeted not against black Tunisians, but against the thousands of sub-Saharan newcomers – a mix of students and of migrants trying to get to Europe. And it has set off a “spiral of violence” against them, said Louis Celestin in Guinée News (Conakry) – there are numerous accounts of people being attacked with machetes; of gangs of young men kicking down the doors of houses and dragging black migrant families into the street, forcing them to watch their possessions being burned.

Racial tensions have long simmered beneath Tunisia’s “ostensibly progressive surface”, said Simon Speakman Cordall in Foreign Policy (Washington). But they have been hugely exacerbated by Saied’s campaign calling on Tunisians to report undocumented migrants to authorities: the security services have arrested black migrants en masse; racism has come to “define their lives”.

How sad that it has come to this, said Hafed Al-Ghwell in Arab News (Riyadh). When Tunisians elected Saied, a former law professor, they believed he could almost “single-handedly” piece together the foundations on which a resilient democracy could be built: but that takes the sort of “tireless” work for which Saied has shown no appetite whatsoever. Instead, he has focused solely on “clinging to power” – leaving the dreams of democracy that Tunisians once harboured “all but buried”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 years

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 yearsfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?Talking Point Goverment under pressure to prohibit breed blamed for series of fatal attacks

-

The spiralling global rice crisis

The spiralling global rice crisisfeature India’s decision to ban exports is starting to have a domino effect around the world

-

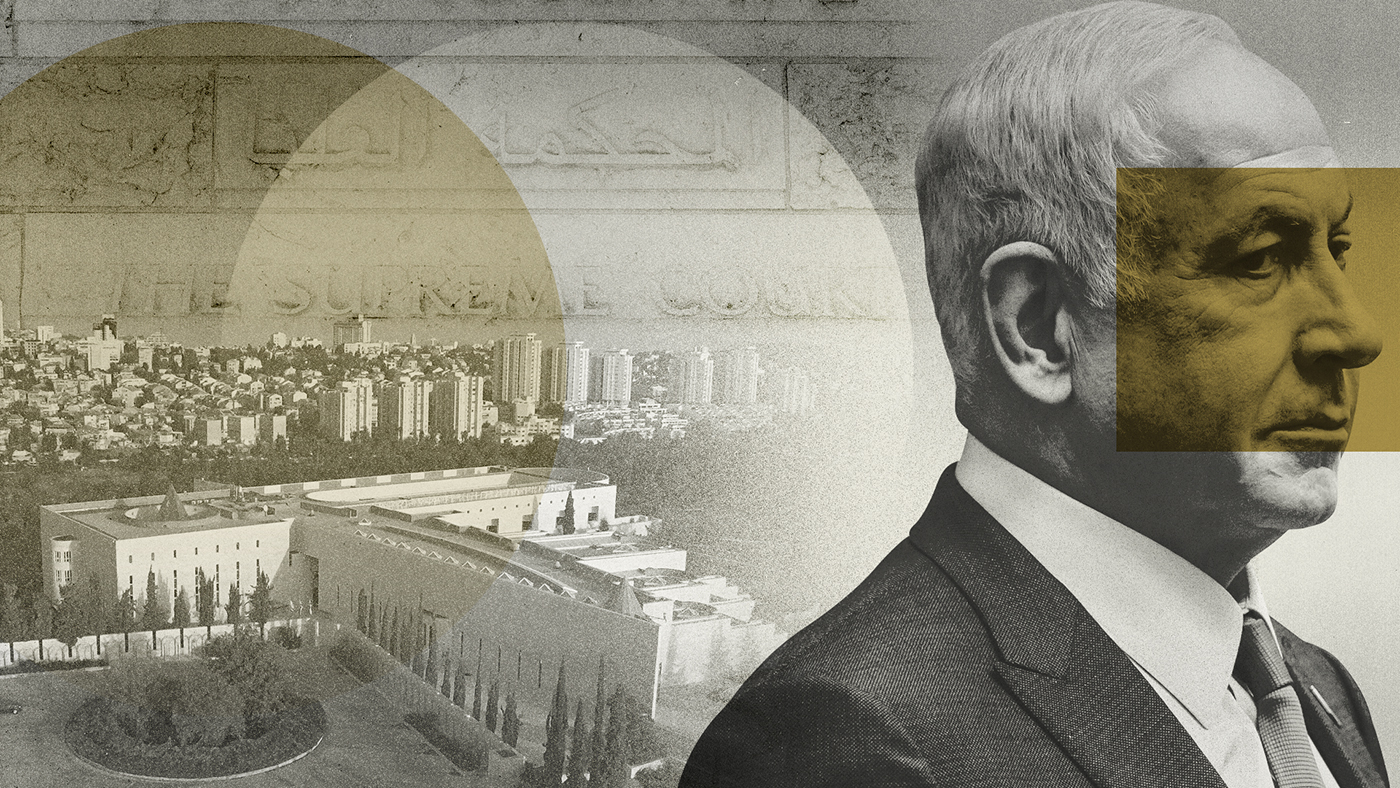

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

A country still in crisis: Lebanon three years on from Beirut blast

A country still in crisis: Lebanon three years on from Beirut blastfeature Political, economic and criminal dramas are causing a damaging stalemate in the Middle East nation

-

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wife

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wifefeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Ghana abolishes the death penalty

Ghana abolishes the death penaltyfeature It joins a growing list of African countries which are turning away from capital punishment

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders