How locust swarms ‘the size of Luxembourg’ are plaguing East Africa

Over the past two years, locusts have ravaged swathes of East Africa. But the cure for the problem may also have dire consequences

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most of the time, the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria, is an innocuous grasshopper: a green or brown short-winged insect that lives a solitary life in the deserts of Africa, Arabia and Asia. But in certain conditions – when there’s lots of moisture and vegetation flourishes – these locusts enter a “gregarious phase”, and undergo a remarkable transformation.

Their brains change, they turn yellow and black, and their wings grow. Most importantly, they become attracted to each other and start joining together in swarms which can reach a density of 15 million insects per square mile, and travel up to 90 miles in a day. Since late 2019, vast clouds of these locusts have devastated parts of the Horn of Africa, devouring crops and pasture, triggering a huge operation to track and kill them.

Where did the locusts come from?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2018, two unusual cyclones – linked to climate change – deposited rain in the remote Empty Quarter of the Arabian peninsula, which led to an 8,000-fold increase in locust numbers there.

In 2019, strong winds blew the growing swarms first into Yemen, then across the Red Sea into Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Kenya, where their populations were further boosted by a wet autumn, and a cyclone in Somalia – paving the way for a major emergency last year. Billions of the insects swept on, into Uganda, South Sudan and Tanzania, going on to affect a total of 23 countries, from Sudan to Iran to Pakistan.

How big were the plagues?

In Kenya, they were the worst in 70 years. When they arrived in East Africa, witnesses said it was “like an umbrella had covered the sky”. “The first swarms we saw were massive – three or four kilometres wide and a thousand metres deep,” Mark Taylor, a farmer in the Laikipia region of northern Kenya, told The Sunday Times.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When the locusts settled on trees, there were “so many of them that branches broke under the weight”. Locust swarms can vary from less than one square kilometre to several hundred square kilometres. There can be at least 40 million and sometimes as many as 80 million locust adults in each square kilometre. One swarm in northern Kenya was reported to have reached 2,400 square kilometres in size – an area the size of Luxembourg.

How bad was the damage?

Locusts eat their body weight in food every day; a small swarm covering one square kilometre can eat the same amount as 35,000 people. So when they descended on East Africa, vast swathes of vegetation were consumed within minutes. “They attacked everything,” says Mark Taylor. “Fifty-four hectares [133 acres] were destroyed just like that.”

In Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia alone, 19 million farmers and herders suffered severe damage to their livelihoods. Some 200,000 hectares of land were damaged in Ethiopia alone between January and October last year. And without intervention by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the consequences could have been far graver.

What did the UN do?

When the crisis first hit, countries in East Africa were woefully under-prepared to deal with an invasion on such a scale. The FAO, too, was caught off guard by the size of the challenge. Yet it quickly gathered resources and before long began a massive aerial and ground assault. It assembled a “locust fighting force” made up of 28 airplanes and helicopters, 260 ground units, and some 3,000 newly trained spotters and control operators.

Planes and teams of young volunteers armed with knapsack sprayers doused an area of two million hectares with almost half a million gallons of chemical insecticides, at a cost of $219m.

The FAO estimates that this action saved the livelihoods of 40 million people, and crop and livestock production worth $1.7bn. Yet the response has raised alarm bells among experts, who warn it could have dire consequences for the environment.

Why might the consequences be dire?

Because of the pesticides being used – in particular, three organophosphates: chlorpyrifos, fenitrothion and malathion. Sometimes referred to as “junior-strength nerve agents” because of their kinship to sarin gas, these pesticides are banned in Europe and much of the US.

There are also concerns about another, deltamethrin. All four chemical insecticides are classified by the FAO itself as posing a high risk to bees, at least a medium risk to ants and termites, and a low risk to birds; it recommends that they should be used only as a last resort.

The FAO’s list of pesticides hasn’t been reassessed in six years, despite the world becoming more environmentally conscious in that time. Activists claim that, as well as causing extensive damage to biodiversity, these chemicals harm livestock and have led to increased cancer rates in villages near where they have been used. They question why (more expensive) organic products that lose their potency within 24 hours of use haven’t been employed instead.

Has the risk gone away?

No. Kenya declared itself locust-free on 1 November, but there were reports of a re-invasion in parts of the country just a day later. Two weeks earlier, the FAO had warned that swarms could migrate to other areas of East Africa as dryer weather sets in. And though the situation isn’t as severe as it has been, locusts remain present in countries including Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

The FAO is maintaining its surveillance and control missions. There are particular fears that locust swarms forming in northern Ethiopia could aggravate severe food shortages in the country’s war-torn Tigray region, where some 900,000 people are estimated to already be at risk of famine. And in Somalia, an FAO-led operation has already begun spraying again – using the same cocktail of insecticides as in the past.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 years

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 yearsfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?Talking Point Goverment under pressure to prohibit breed blamed for series of fatal attacks

-

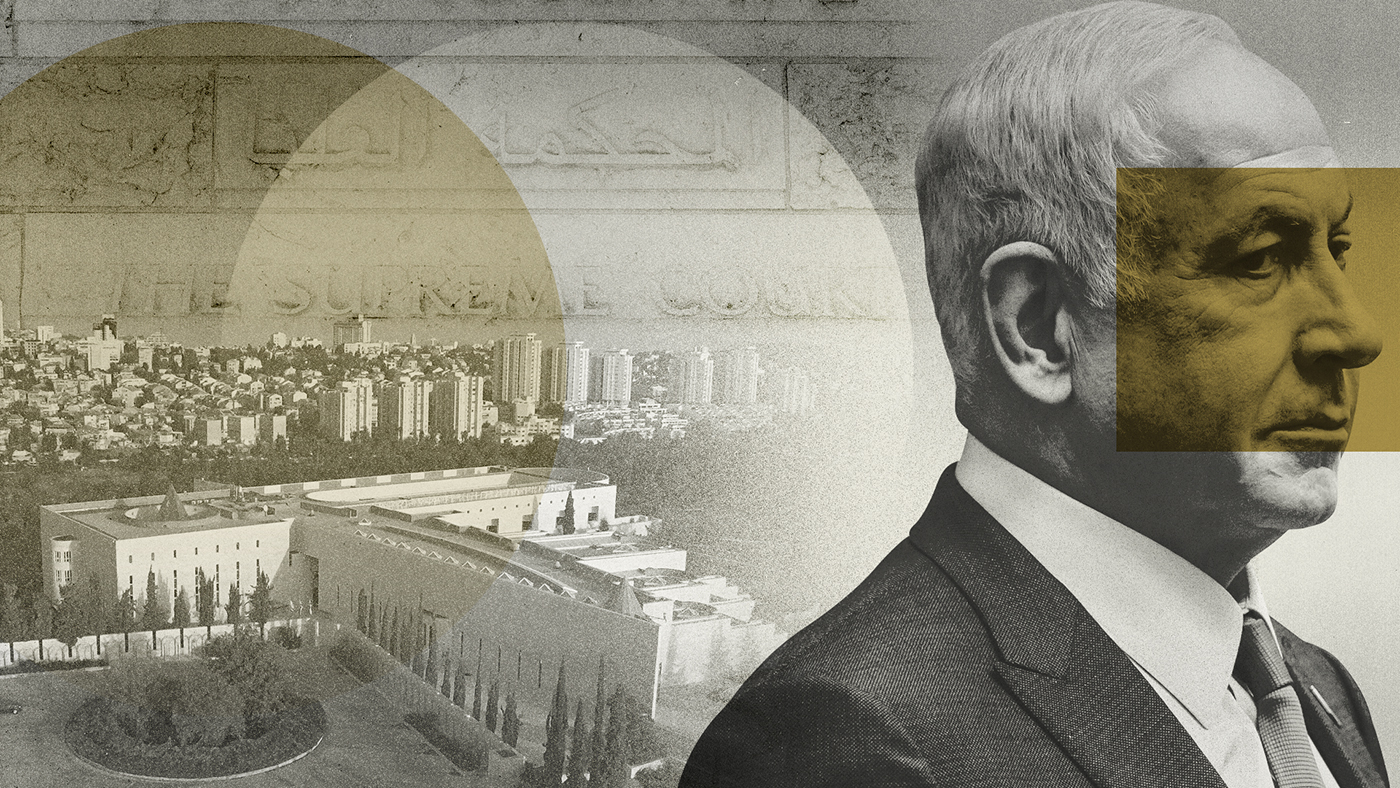

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wife

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wifefeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders

-

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled haven

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled havenfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classes

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classesfeature Reports of the death of the Chinese economy may be greatly exaggerated say analysts

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some