School shootings: what can be done to stop them?

The shooting at a school in Uvalde has reignited the debate over gun control in America

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The children of Robb Elementary School in Uvalde had just taken part in an end-of-term awards ceremony when 18-year-old Salvador Ramos entered the school at 11.33am through an unlocked back door. He was carrying an assault-style rifle and hundreds of rounds of ammunition. “It’s time to die,” he told the children in two adjoining classrooms. Seven police officers arrived within minutes, but stood by while the shooter picked off his victims. By about midday, 19 armed officers were in a hallway, outside the classrooms. Inside, terrified children were still calling 911. Yet it was not until just before 1pm that a tactical unit broke in, and shot the gunman dead. By then, he had fired 142 rounds, and killed 19 children and two teachers.

What were the police thinking, asked David A. Graham in The Atlantic. Since the Columbine massacre, the consensus has been that in “active shooter situations”, officers should intervene as soon as possible, not wait for a tactical team. Experts are baffled by the failure to follow protocol, and parents are rightly angry. And yet focusing on these failures risks eclipsing the bigger picture. By the time the police arrive at a shooting, it is already too late; the real failure took place days earlier, when a teenager was able to legally acquire two AR-15-style semi-automatic rifles and 1,657 rounds of ammunition. The fact that we have to demand that our police act more courageously, and risk their lives to prevent the slaughter of children in their own schools, is in itself a mark of a “broken society”.

We should do something about school shootings, said Dan McLaughlin in the National Review, but we have to focus on what is possible. President Biden is again calling for sweeping new gun controls, but here is the problem: there are an estimated 400 million guns in circulation in the US; 40% of households own guns; and the vast majority of owners are law-abiding. Attempts to significantly limit the availability of firearms repeatedly fail because they simply do not have the popular support to succeed. So if there is not much we can do about the guns, we could do something about schools. But there are almost 100,000 public schools in the US, and beefing up their security would also be a major undertaking; most will never be the scene of shootings; and many parents don’t want their children to go to school in a militarised zone. So what if we instead focus on the shooters? In 56 years, there have been 13 mass school shootings, involving 15 shooters. “Now we’re in a more manageable universe.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We know what these shooters are like, said Ross Douthat in The New York Times: they’re “troubled, socially awkward” young men. They’re not usually gun experts, able to retrofit guns to make them more lethal, nor are they the type to navigate black markets to buy guns; and “they often expose their instability and intentions in advance”. So it must be possible to impede their access to weapons – by, say, requiring under-25s to undergo fuller background checks, including mental-health screenings and social media audits, before they can buy assault rifles – without it affecting the average gun-loving American. That would be a start, said Pamela Paul in the same paper. But we must also tackle this fetish we have for guns, via a public-health campaign aimed at persuading boys, in particular, that guns aren’t cool. Before you dismiss the idea, consider that the seatbelt campaign drove usage from 14% to 80%; and that efforts to deglamorise smoking are also paying dividends. Even if it only shifts the dial a little, it has to be worth a try.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

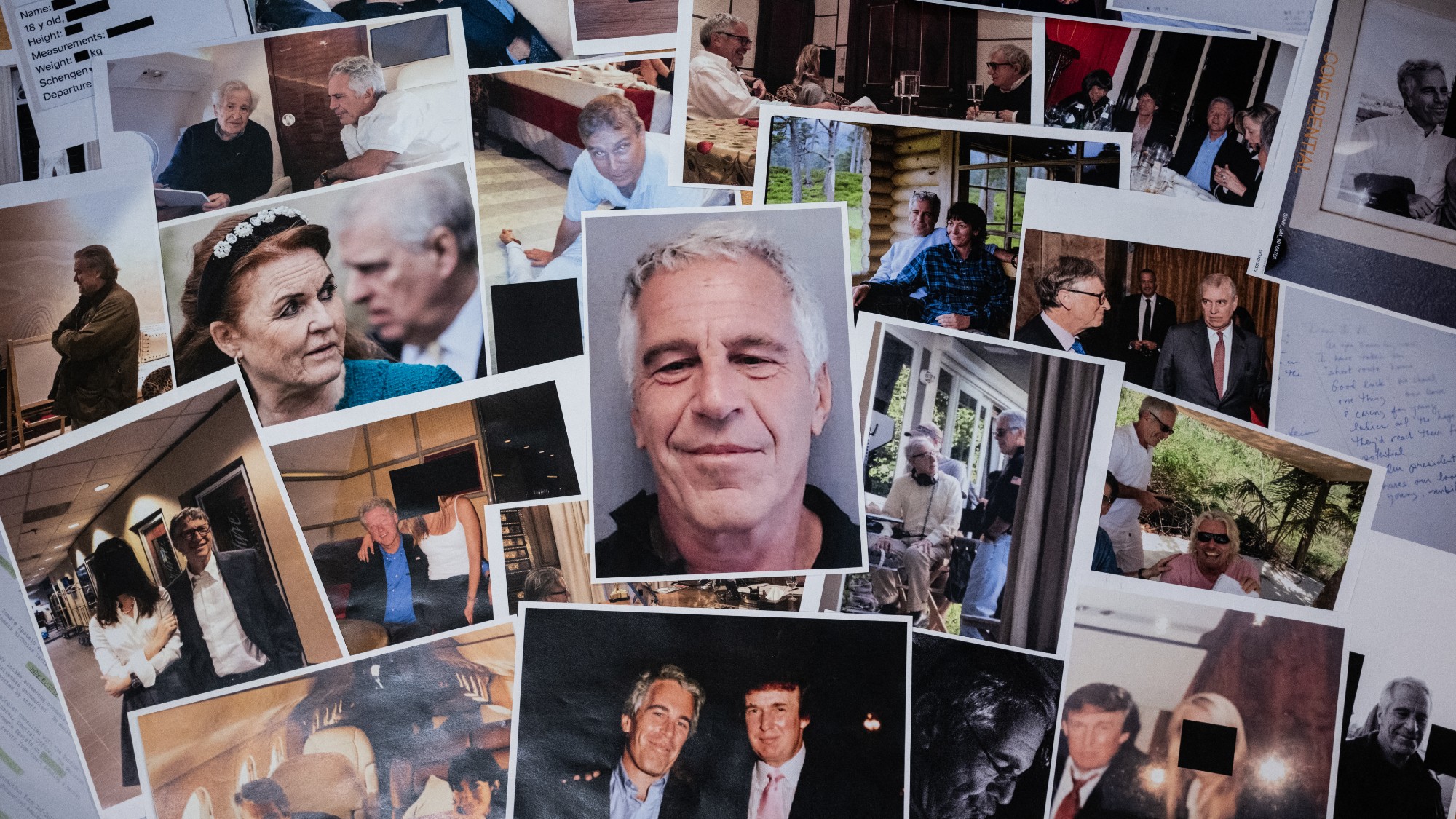

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shooting

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shootingTalking Points Questions surround a federal law called the Clery Act

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shooting

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shootingSpeed Read Police did not share the identities of the officers or the slain suspect, nor the motive or the focus of the still-active investigation

-

Trump lambasts crime, but his administration is cutting gun violence prevention

Trump lambasts crime, but his administration is cutting gun violence preventionThe Explainer The DOJ has canceled at least $500 million in public safety grants

-

Aimee Betro: the Wisconsin woman who came to Birmingham to kill

Aimee Betro: the Wisconsin woman who came to Birmingham to killIn the Spotlight US hitwoman wore a niqab in online lover's revenge plot

-

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?Feature The jury cleared Sean Combs of major charges but found him guilty of lesser offenses