How the civil service works – and why critics say it needs reform

Keir Starmer wants to 'rewire' Whitehall, which he has claimed is too 'comfortable in the tepid bath of managed decline'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Keir Starmer has promised "a renewed civil service; more agile, mission-focused and more productive". Like every government in recent history, his is pushing for improved "delivery"; for better technical and digital skills; and for performance-related pay for senior civil servants, with possible dismissal for under-performers.

It wants to move more civil servants out of London, relocating 12,000 jobs to, among others, Manchester, Cardiff, Birmingham and Aberdeen (this is a recurring theme of reform efforts since the 1980s). And a review of arm's-length bodies is under way to bring more services under direct ministerial control (the world's largest quango, NHS England, has already been abolished).

How many civil servants are there?

As of December 2024, there were 548,000 civil servants in the UK, or 514,000 full-time equivalent employees. About six million, or 18% of the UK's 34 million workers, work for the public sector, but only 1.6% of the British workforce are civil servants; most public sector workers are employed by councils, NHS trusts, police forces and so on. (Prison officers, being employed by the Ministry of Justice, are civil servants; police are not.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what people largely mean by the civil service is the officials who staff the machinery of central government: the UK's 24 ministerial departments – known collectively as Whitehall – its 20 non-ministerial departments (such as HM Revenue and Customs or HM Land Registry), and some 305 "arm's-length bodies" (from the Environment Agency to the Care Quality Commission).

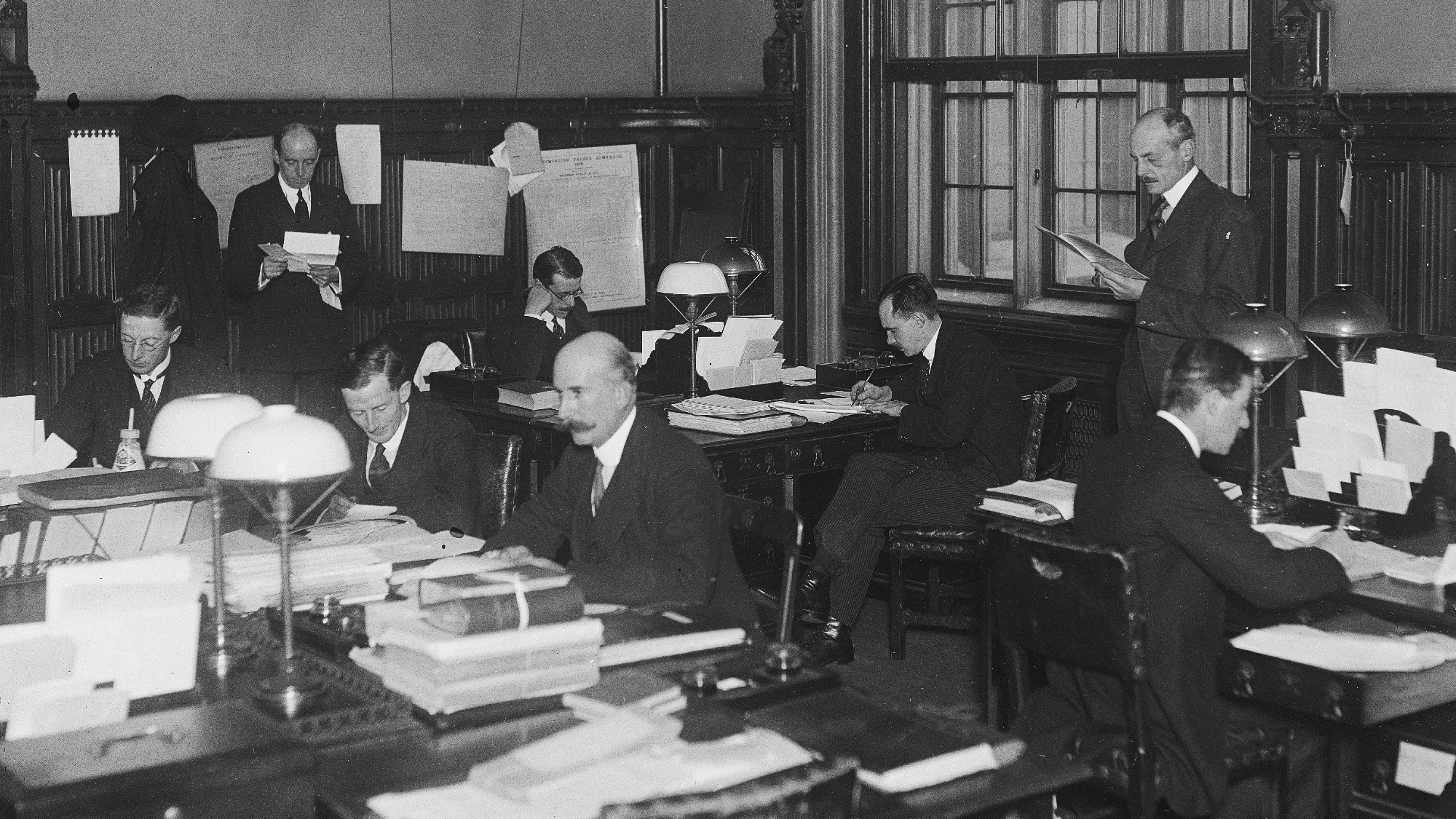

How was the civil service created?

The modern civil service is usually dated back to the Northcote-Trevelyan Report of 1854. Finding a Whitehall system staffed by men of "slender ability" selected mostly by patronage, its authors recommended the creation of a small elite corps of administrators chosen by open examination: "an efficient body of permanent officers… possessing sufficient independence, character, ability and experience to be able to advise, assist, and to some extent influence" government ministers.

Their recommendations were implemented in 1870, and they created a system that endured for generations and was much admired, at home and abroad, for its high standards of integrity, professionalism, honesty and political neutrality. It was often likened to a Rolls-Royce; one US journalist called it "the incorruptible spinal column of England".

What's the problem now?

Successive governments, from Tony Blair's to Boris Johnson's to Starmer's, have been frustrated by shortcomings in Whitehall's ability to deliver their chosen policies, to respond to crises and threats, and even to provide basic services.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A few well-known examples of dysfunction might include the failure of the Covid test-and-trace programme; the Ministry of Defence's very poor record on arms procurement; the attempt to create a national electronic record system for the NHS, cancelled in 2011 at a cost of more than £10 billion; and the long-running series of problems at the Home Office, from the wrongful release of foreign offenders to the Windrush scandal.

Beyond that, ministers of all political stripes have complained that when they pull the levers of government, little happens. Blair said the civil service was like "a shiny Rolls-Royce parked outside the door of Downing Street", which he was "not allowed to drive".

Why has this happened?

According to Francis Maude, David Cameron's Cabinet Office minister, who published a review in 2023, there is a remarkable consistency in the criticisms made, all the way from the Fulton Report of 1968 to those made by Dominic Cummings and Michael Gove under Johnson.

These include: shortages of technical skills, particularly in data and science, and of commercial experience; a high staff "churn", as civil servants are moved from job to job; an aversion to risk and innovation; an over-reliance on process; poor staff management, with few rewards for success and few penalties for failure; and, as a result, a gulf between policy and implementation. These issues are often said to be rooted in civil service culture.

What's wrong with the culture?

Critics say there is an excessive reliance on "generalists" recruited into the "fast stream", often Oxbridge-educated humanities graduates with drafting and "courtier skills", who dominate the top cadre (once satirised in the form of Sir Humphrey in "Yes Minister", more recently dubbed "the Blob" by Gove). They are, it is said, culturally homogenous, with shared metropolitan liberal attitudes, and often resistant to policy change – particularly if it comes from the Eurosceptic political Right.

According to Maude, there is a damaging "disparity of esteem" between the officials who formulate policy, who occupy most of the highest grades, and those charged with implementation and with technical expertise. This, he suggests, may explain the poor record on delivery.

Are these criticisms fair?

It's worth noting that they are made largely by politicians, while civil servants are constrained from speaking publicly. And the latter are often "blamed for policy failures by the ministers they serve", says the former cabinet secretary Gus O'Donnell. The tasks the civil service performs are intrinsically complex, and policies shift not just when governments change, but frequently from week to week; "churn" among ministers is far worse than among civil servants.

Constant criticism lowers morale, too: in the latest civil service survey, only 35% said they wanted to stay in their organisation for the next three years. Pay, meanwhile, is not high. The permanent secretary to the Treasury, its top civil servant, earns £160,000; a FTSE 100 CEO earns around 25 times that. In technical areas – in pensions or IT, say – the disparity is particularly acute, which accounts for skills shortages.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

‘Melania’: A film about nothing

‘Melania’: A film about nothingFeature Not telling all

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away

-

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photo

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photoFeature An image of Liam Conejo Ramos being detained lit up social media

-

The price of forgiveness

The price of forgivenessFeature Trump’s unprecedented use of pardons has turned clemency into a big business.

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?