The next Prohibition

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

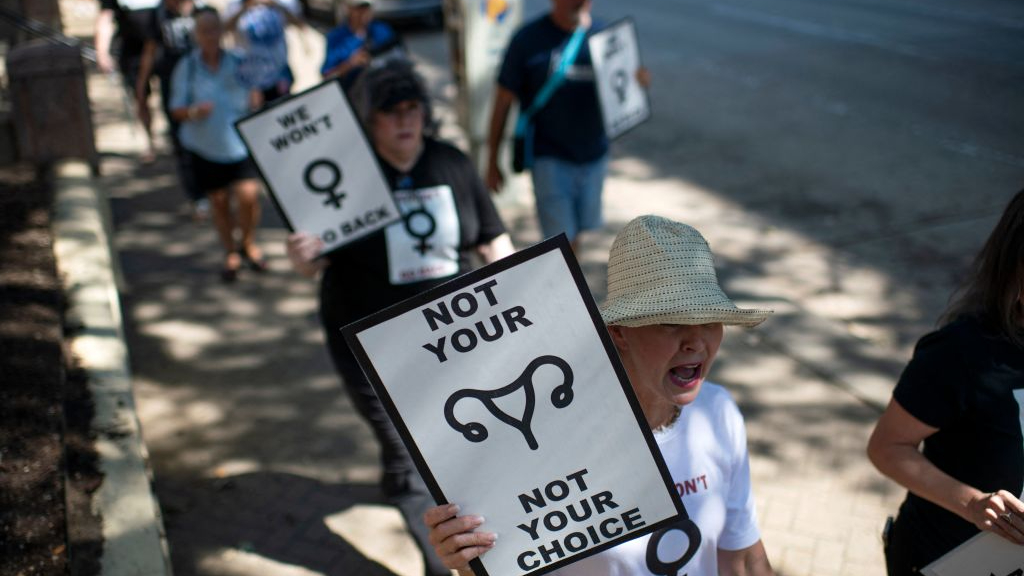

It was the culmination of a decades-long movement fueled by religious fervor. In 1919, an America with a fondness for drink nonetheless adopted a constitutional amendment banning the "manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors." Prohibition immediately divided the country, and gave rise to sophisticated bootleg operations, smuggling, speakeasies, and the growth of organized crime. With public support waning after 13 tumultuous years, Congress abandoned the great dry experiment in 1933. It was not the first, nor the last, time governments have failed to prohibit a substance or behavior for which there is great public demand. When there is a want, there is always a way.

Banning abortion will be even more difficult than booze. Abortion will remain legal in roughly half the states, and state borders are permeable. Medications that induce safe abortions at home are easily obtained through the mail. And instead of whiskey, drugs, or guns, states will be trying to police women's uteruses, which are inconveniently located inside their bodies. As history shows, women with unwanted pregnancies will do whatever is necessary to end them, even at the risk of their lives. So to dramatically reduce abortion, this Prohibition must stop women from having unwanted pregnancies — which means stopping them from having sex. That is indeed the goal of many evangelicals and Catholics in the right-to-life movement, who believe that the only legitimate sexual expression is between a married heterosexual couple not using birth control. All else is sin. In National Review, pro-life campaigner Alexandra Desanctis helpfully explains that in the view of the movement (and that of five Supreme Court justices), no woman will be "forced to give birth." That's because there is no "fundamental right" to have "sex without consequences," Desanctis says. Once a (bad) woman has sex, she has surrendered her choice. The past is the future.

This is the editor's letter in the current issue of The Week magazine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

William Falk is editor-in-chief of The Week, and has held that role since the magazine's first issue in 2001. He has previously been a reporter, columnist, and editor at the Gannett Westchester Newspapers and at Newsday, where he was part of two reporting teams that won Pulitzer Prizes.

-

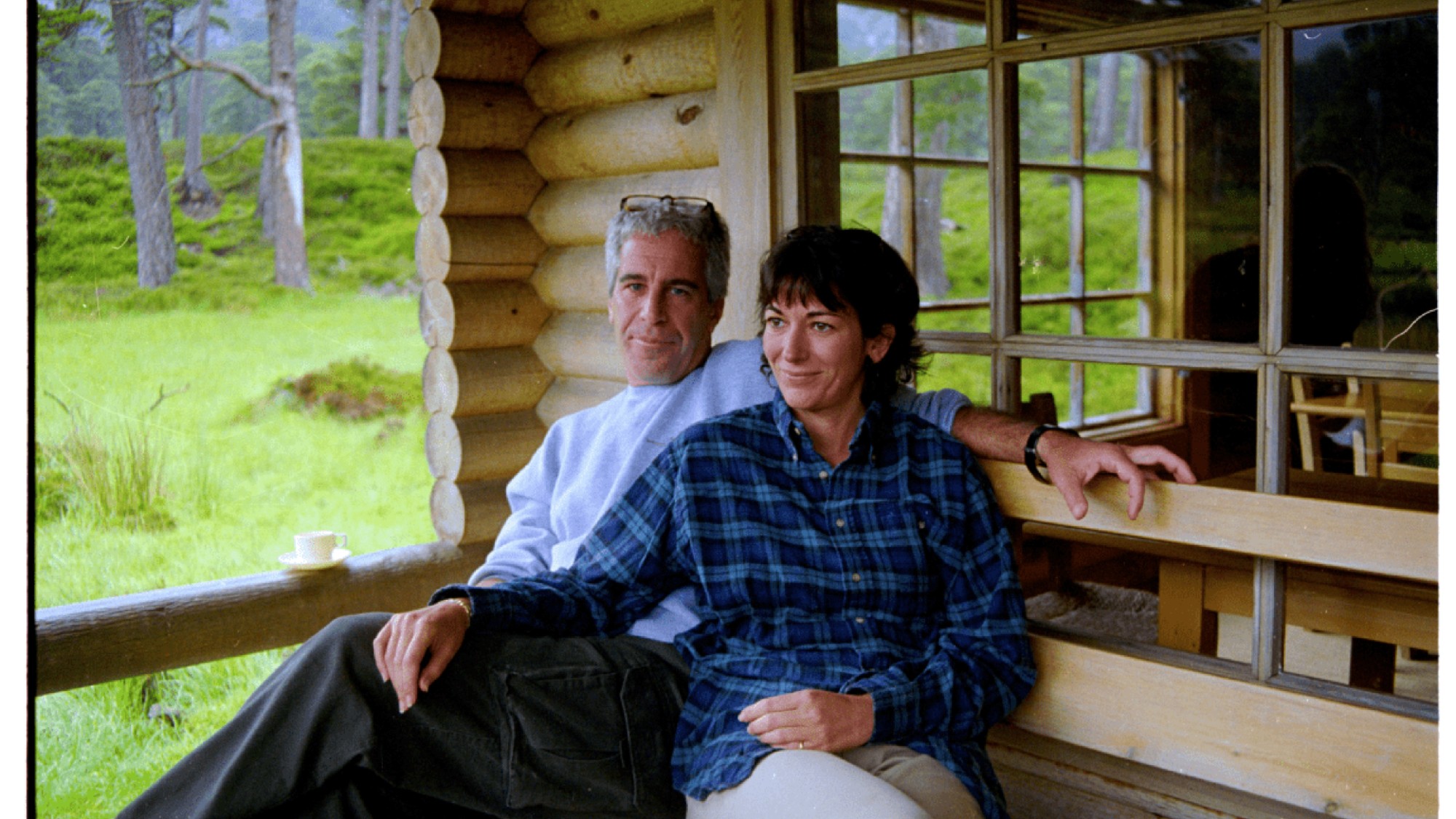

Lawmakers say Epstein files implicate 6 more men

Lawmakers say Epstein files implicate 6 more menSpeed Read The Trump department apparently blacked out the names of several people who should have been identified

-

Maxwell pleads 5th, offers Epstein answers for pardon

Maxwell pleads 5th, offers Epstein answers for pardonSpeed Read She offered to talk only if she first received a pardon from President Donald Trump

-

Political cartoons for February 10

Political cartoons for February 10Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include halftime hate, the America First Games, and Cupid's woe

-

Is the UK about to decriminalise abortion?

Is the UK about to decriminalise abortion?Talking Point A rise in prosecutions has led Labour MPs to challenge the UK's abortion laws

-

Abortions rise to record level 'due to cost of living'

Abortions rise to record level 'due to cost of living'Speed Read Low-income women face 'heart-breaking' choice, warns abortion charity chief

-

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinics

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinicsUnder The Radar Giorgia Meloni scores a political 'victory' but will it make much difference in practice?

-

France enshrines abortion rights in constitution

France enshrines abortion rights in constitutionspeed read It became the first country to make abortion a constitutional right

-

Texas judge approves abortion of nonviable fetus, drawing threat from Texas attorney general

Texas judge approves abortion of nonviable fetus, drawing threat from Texas attorney generalSpeed Read Kate Cox petitioned to terminate her doomed pregnancy, salvaging her uterus and the option to try for more children

-

Ohio voters defeat GOP measure to raise referendum threshold

Ohio voters defeat GOP measure to raise referendum thresholdSpeed Read

-

Ohio is voting on whether to raise the bar on referendums — and a popular abortion amendment

Ohio is voting on whether to raise the bar on referendums — and a popular abortion amendmentSpeed Read

-

Abortion law reform: a question of safety?

Abortion law reform: a question of safety?Talking Point Jailing of woman who took abortion pills after legal limit leads to calls to scrap ‘archaic’ 1861 legislation