Florida, DeSantis and the long history of election law hardball

These partisan maneuvers often come back to haunt their architects

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Republican-controlled Florida legislature recently changed a "resign-to-run" statute that prevented elected officials from running for other offices without first stepping down from their existing position. The revised statute exempts anyone running for president or vice president from the provision. Why did Florida Republicans do this? And how common is it to change state laws in this fashion?

The DeSantis factor

"This isn't just for our governor," said GOP state Rep. Ralph Massullo after his fellow Republicans changed the state's resign-to-run law. "It's for anyone in politics." But despite Massullo's protestations, the bill was a transparent maneuver to allow Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) to pursue his long-rumored White House bid. It is actually the third time that the legislature has changed its election laws to benefit a specific office-seeker – in 2008, the GOP legislature eased resign-to-run requirements to aid then-Gov. Charlie Crist's potential selection as John McCain's running mate. And then in 2018, the legislature restored the law with a carve-out to allow then-Gov. Rick Scott to run for the U.S. Senate.

There is a rich history in the United States of partisan tweaks to election laws designed to thwart or grease the skids for particular people or parties. In 2004, Massachusetts Democrats, hopeful that then-Sen. John Kerry would win the presidency against incumbent Republican George W. Bush, passed a law requiring a special election within 145-160 days after a vacancy. The governor, at the time Republican Mitt Romney, wouldn't even have been able to make a temporary appointment had Kerry won. State Democrats then tweaked the law again in 2009 so that Democratic Gov. Deval Patrick could appoint a temporary replacement for the late Sen. Ted Kennedy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A mixed history

Vacancy games are played by both sides. In 2021, the Republican supermajority in the Kentucky state legislature passed a law requiring the governor to appoint a senator from the same party as the incumbent should a vacancy occur. Voters in the deep red state had unexpectedly elected a Democrat, Andy Beshear, governor in 2019. Kentucky's senior senator, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, was 79 when the law was passed and rumored to either be in poor health or considering resignation. Kentucky Republicans didn't seem too worried that there will be blowback from the change. With supermajorities in the state legislature, Republicans figure they can just change the law back if a Democrat ever wins another Senate seat there under a GOP governor. And the voting public did not seem terribly bothered by any of it, re-electing McConnell by almost 20 points over a generously funded Democratic challenger.

These partisan maneuvers tend to have a shelf life, and often come back to haunt their architects. The whole Massachusetts ordeal would ultimately boomerang on Democrats as Republican Scott Brown won the 2010 Senate special election, immediately depriving President Barack Obama of a Senate supermajority and depriving the Democratic majority of the opportunity to pass more legislation. State Democrats almost certainly would have changed the law once again if Sen. Elizabeth Warren had joined President Biden's cabinet after 2020.

The rise of 'constitutional hardball'

All of these gambits fall under the rubric of what legal scholar Mark Tushnet termed "constitutional hardball." In a now-famous UIC Law Review essay, Tushnet defined the idea as partisan schemes "that are without much question within the bounds of existing constitutional doctrine and practice but that are nonetheless in some tension with existing pre-constitutional understandings." In other words, constitutional hardball refers to cut-throat political tactics that may technically be permissible under the legal order but that nevertheless are violations of informal understandings and practices. A good example from recent history was then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's decision not to hold hearings for Merrick Garland, Obama's pick to fill the late Antonin Scalia's seat on the Supreme Court in 2016. When deployed over and over again, hardball tends to erode trust between political actors, who are then incentivized to pursue maximal political gains at the expense of the future stability of the system.

Election laws should, in theory, represent important principles that transcend the needs of partisan politicians at any given moment. Florida presumably had a resign-to-run law in the first place because lawmakers believed that state executives should focus on the task at hand rather than trying to simultaneously govern the state and pursue higher office. When the law becomes just another extension of partisan combat, subject to revision after revision based on changing circumstances, it undermines public faith in the integrity of the political system and breeds justifiable contempt for the elected officials doing the manipulating.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

DeSantis, however, would hardly be the first presidential candidate whose state backers unshackled him from an inconvenient obstacle. In April 1959, Texas Democrats passed what became known as the "LBJ Law," repealing a statute that prevented state officials from running simultaneously for multiple offices. It allowed Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Baines Johnson to seek election as John F. Kennedy's vice president and also to run for his Senate seat. Kennedy and Johnson won their White House bid, and Johnson's appointed replacement, William Blakley, lost his 1961 special election to Republican Jim Tower. Democrats have yet to recover the seat, which has remained in GOP hands for 62 years.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

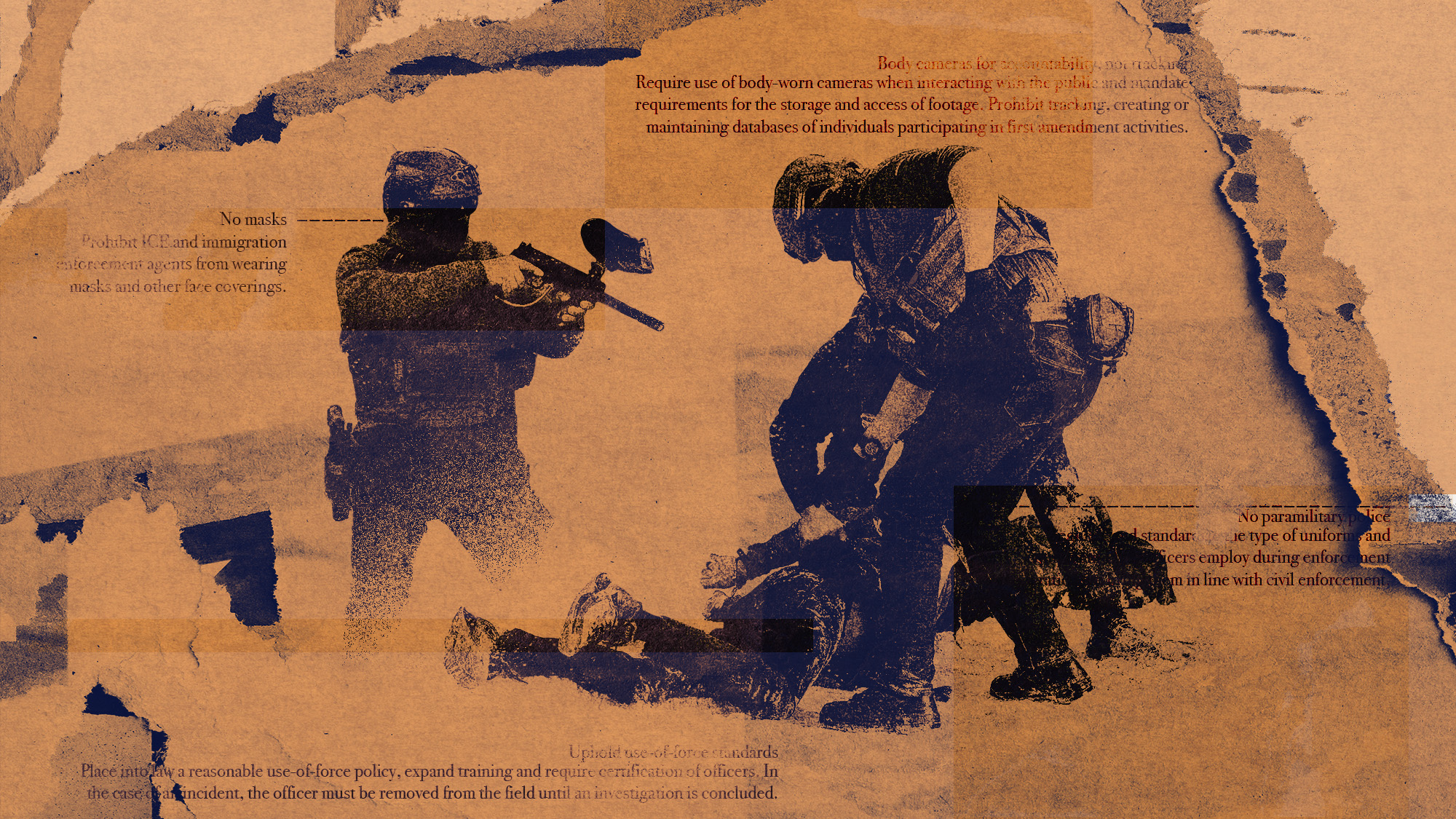

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressure

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressureSpeed Read Halligan’s position had already been considered vacant by at least one judge

-

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leaders

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leadersSpeed Read Seventeen GOP lawmakers joined all Democrats in the vote

-

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conference

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conferenceIN THE SPOTLIGHT ‘Americafest 2025’ was a who’s who of right-wing heavyweights eager to settle scores and lay claim to the future of MAGA

-

House GOP revolt forces vote on ACA subsidies

House GOP revolt forces vote on ACA subsidiesSpeed Read The new health care bill would lower some costs but not extend expiring Affordable Care Act subsidies