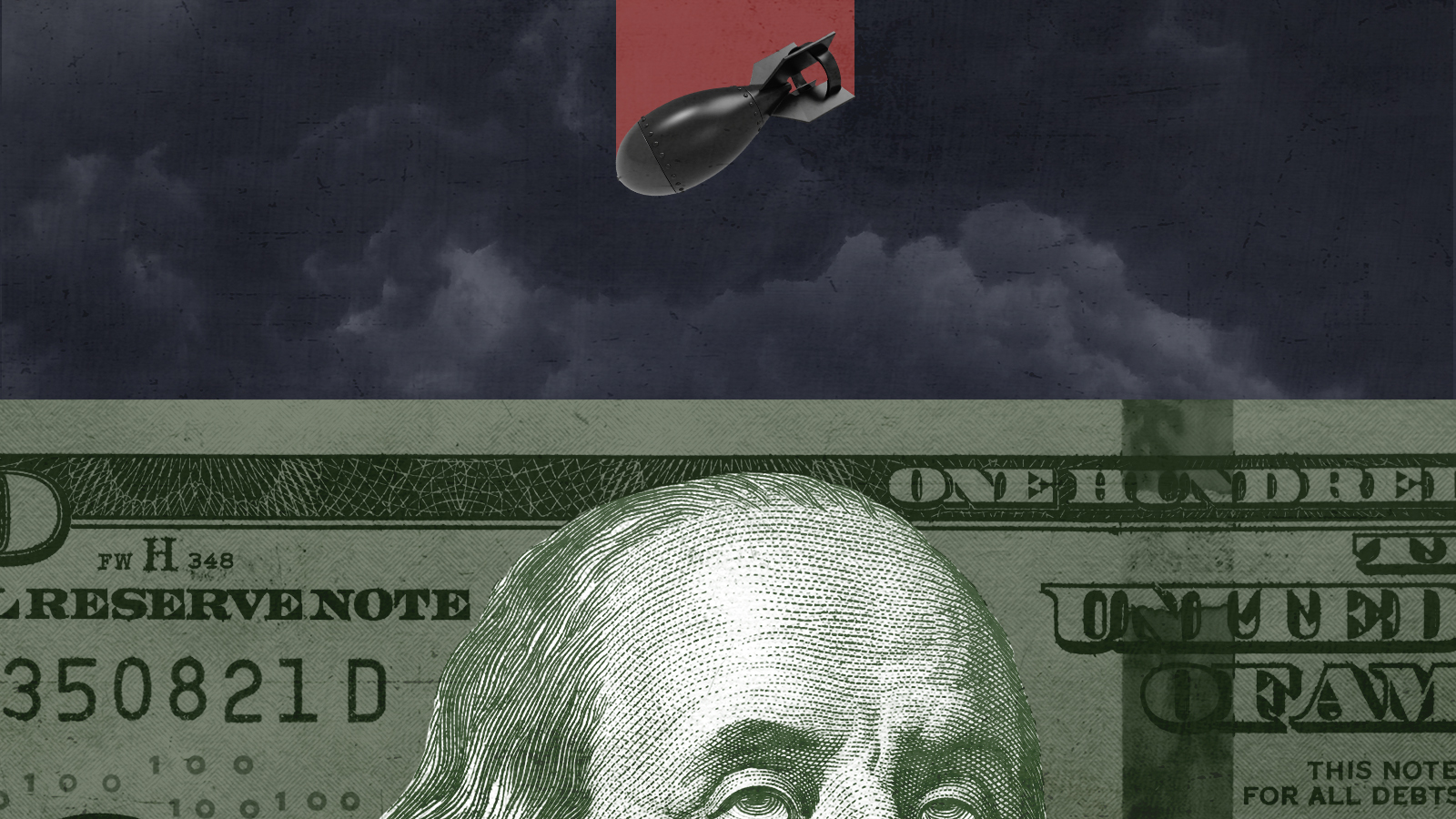

Threats of nuclear war are the last thing the economy needed

Economic pain arrives as the end of the Cold War ends

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's one thing for North Korea — a country that hasn't fought a war since 1953 — to saber rattle with its small nuclear arsenal (the nation's "treasured sword," according to dictator Kim Jong-un). It's quite another when Vladimir Putin does it. Russia has nearly 6,000 nuclear warheads, and its ongoing invasion of Ukraine is Europe's largest ground war since World War II. Moreover, things don't seem to be going as smoothly or quickly as Putin anticipated. Finally, Russia's nuclear war doctrine suggests a dangerous willingness to engage in a limited nuclear war to win a conventional conflict — especially one, perhaps, inciting economy-crippling sanctions by the rest of the world.

So no wonder the United States and the rest of NATO howled after Putin placed his country's deterrence forces, including nuclear weapons, on high alert, and warned that interference in Ukraine would spark consequences "never before experienced in your history."

Officials at NATO and the U.S. State Department called such rhetoric "dangerous." Indeed, Putin's statement seemed to represent a return to a sort of Cold War-style nuclear brinkmanship not seen since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis or maybe the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. It may also mark a return to nuclear war as something global politicians, business leaders, and investors need to consider in ways they haven't since the collapse of the Soviet Union three decades ago.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some already are.

On Monday, BCA, a boutique investment research firm, distributed a note that's gone viral on social media. Provocatively titled, "Rising Risk of a Nuclear Apocalypse," the piece assumes that even if Russia is successful in turning Ukraine into a de facto satellite state, the inevitable insurgency would drain Russian resources and erode Putin's political standing. And if Putin concludes he has no future, maybe he'll conclude the same about the rest of us. As the firm ominously concludes: "The risk of Armageddon has risen dramatically. ... Although there's a huge margin of error around any estimate, subjectively, we would assign an uncomfortably high 10 percent chance of a civilization-ending global nuclear war over the next 12 months."

Now, I read a lot of investment research, and you don't see many notes like that one. The only similar one that immediately comes to mind is a famous 2011 research piece from former Citigroup Chief Economist Willem Buiter on a potential breakup of the European Union. Buiter said that even if such a dissolution did not "represent a prelude to a return to the ... civil wars and wars that were the bread and butter of European history between the fall of the Roman empire and the gradual emergence of the European Union," it might well mire the world in "years of global depression."

Almost forgot: BCA is advising investors to stay "bullish on stocks over a 12-month horizon" even if there are a few moments of nuclear panic here and there. (The firm notes, for instance, that Google searches for nuclear war are "already spiking.") It's a sensible call, when you think about it for a moment: In a "civilization-ending" atomic holocaust, portfolio values aren't going to matter.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But that doesn't mean that there might not be significant economic consequences to Putin's nuclear threats. Let's start with stocks. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but once the Soviet Union was nyet, investors started valuing equities more highly. Since the end of the Cold War, the stock market's price-earning ratio has rarely been below 18 based on trailing earnings, while during the Cold War it was rarely above 18. There's also economic research suggesting that heightened tensions between the US and USSR during President Ronald Reagan's first term contributed to higher 1980s interest rates by increasing the fear of nuclear war and thus reducing savings through bond buying. (No point in planning for a radioactive rainy day.)

And it's not just financial assets that could be affected. Rising geopolitical risk can dampen economic growth, especially business investment. And right now, risk is spiking to its highest levels since the Iraq war, according to a risk index at the Federal Reserve.

Then there's the impact if Putin exploded a nuke, even a single one to demonstrate his seriousness. As Robert S. Pindyck (MIT Sloan School of Management) and Neng Wang (Columbia Business School) note in their 2012 paper "The Economic and Policy Consequences of Catastrophes," there would be "a reduction in trade and economic activity worldwide, as vast resources would have to be devoted to averting further events."

Of course, that reduced global economic activity would be in addition to the negative impact of the growing global ban on Russian oil imports, such as the one just announced by President Biden. But that's the thing about peace and prosperity: Not having one makes it tough to have the other.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Elon Musk used Starlink, which saved Ukraine, to thwart a Ukrainian attack on Russia's Crimea fleet

Elon Musk used Starlink, which saved Ukraine, to thwart a Ukrainian attack on Russia's Crimea fleetSpeed Read

-

Russia's weaponization of oil and gas exports to neuter Europe on Ukraine is backfiring badly

Russia's weaponization of oil and gas exports to neuter Europe on Ukraine is backfiring badlySpeed Read

-

OPEC+ keeps output unchanged amid uncertainty over fallout from Western price caps on Russian oil

OPEC+ keeps output unchanged amid uncertainty over fallout from Western price caps on Russian oilSpeed Read

-

Sanctions are reportedly hurting Russia's economy and Ukraine war aims, and new oil caps could hit harder

Sanctions are reportedly hurting Russia's economy and Ukraine war aims, and new oil caps could hit harderSpeed Read

-

Oil companies reach record profits amid Russia's war on Ukraine

Oil companies reach record profits amid Russia's war on UkraineSpeed Read

-

Russia's Ukraine invasion will hasten the shift to clean energy, International Energy Agency forecasts

Russia's Ukraine invasion will hasten the shift to clean energy, International Energy Agency forecastsSpeed Read

-

Elon Musk denies report he spoke with Putin before tweeting Kremlin-friendly Ukraine 'peace' plan

Elon Musk denies report he spoke with Putin before tweeting Kremlin-friendly Ukraine 'peace' planSpeed Read

-

Ukraine grain ship clears inspection in Turkey

Ukraine grain ship clears inspection in TurkeySpeed Read