Why the CDC shouldn't hide vaccine data — no matter how ripe for abuse

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

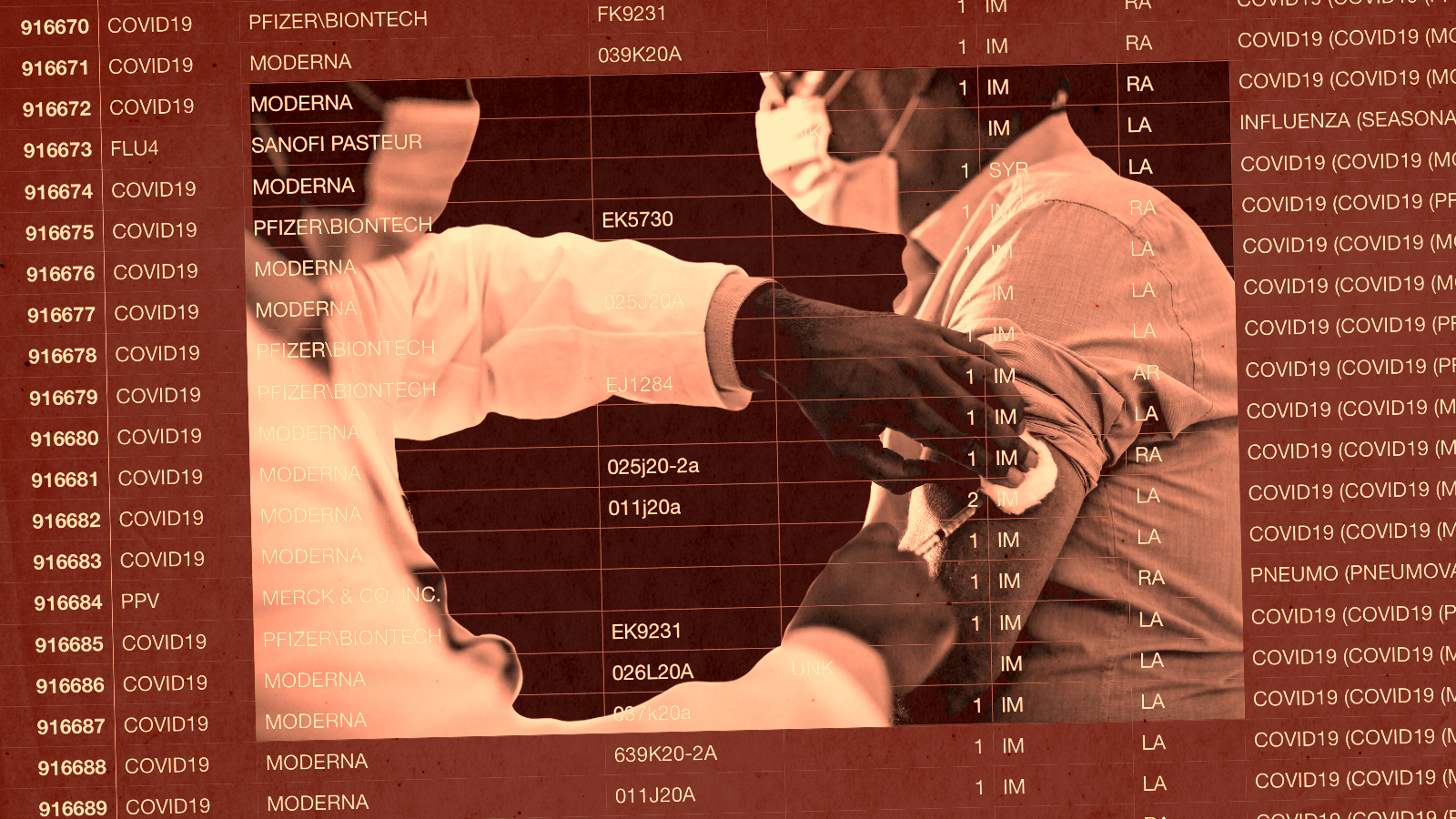

If you've spent much time exploring vaccine safety concerns, you've likely heard of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a database run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to which anyone can submit a report of a suspected vaccine reaction. If you got a COVID-19 vaccine, you may have received a handout, like I did, explaining how to use VAERS.

The database seems like a smart idea. It's intended to serve as a warning system, a digital canary, to detect patterns of bad side effects before many people are harmed. It's difficult to imagine opposing such a database in theory.

But in practice, VAERS gets a bit messy. You see, not only can anyone make a report or access reams of raw data, but the entries aren't verified before publication. Indeed, as a lengthy VAERS disclaimer explains, "[v]accine providers are encouraged to report any clinically significant health problem following vaccination to VAERS, whether or not they believe the vaccine was the cause," and "reports may contain information that is incomplete, inaccurate, coincidental, or unverifiable." Though obviously fake, trollish accounts are deleted (and knowing false reporting is a crime), some fabricated reports may be published.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And though VAERS provides a guide to interpreting its data alongside that disclaimer, whom among us is naive enough to think every user reads it? Realistically, some subset of those accessing VAERS draw uninformed and incorrect conclusions from the data. Frankly, I think there's a real chance I might misread it myself.

So here's the conundrum: If you make a database like this unregulated and accessible to the public, you're inviting bad data and false conclusions. Just this week, a family member sent me a document from Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s anti-vaccine organization which relies significantly on VAERS to make an ill-supported case that childhood vaccinations are responsible for an "epidemic of poor health in American children."

But if you regulate VAERS content or make access more exclusive — well, that's awfully suspicious, isn't it? What are they hiding? I'm very pro-vaccine, but even I would be skeptical if VAERS went private or suddenly started screening its reports. Those changes have their supporters: A Harvard Political Review article in April suggested VAERS "in its current form" may do "more harm than good," and a story on VAERS from anti-misinformation organization First Draft praised an Australian system of only publishing adverse reaction accounts that pass scrutiny from a medical professional.

On balance, I think the current, open approach is the better of these two options. There are risks to trusting people with information, but it's preferable to elite censorship or lies by omission. Still, I can't deny I'm uneasy about the problem of public data VAERS exemplifies. Are we stuck forever with a choice between data chaos and control?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.