Breyer, Kagan, and the fading of 20th-century American Jewish meritocracy

The latest SCOTUS exit symbolizes the declining prominence of a certain kind of American Jew

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Justice Steven Breyer's retirement from the Supreme Court is a perfect Washington story: It's fascinating to the small number of people who follow politics closely and makes little difference to anyone else.

Breyer, who was nominated by a Democratic president, will be replaced by another justice nominated by a Democratic president, who in turn will be a reliable vote for liberal positions on most issues (perhaps with a few signature idiosyncrasies). Unless you're a devoted court watcher, there's not much to see here.

Breyer's retirement holds some sociological interest, though. As recently as 2020, three Jews sat on the Supreme Court — hugely disproportionate to our 2.4 percent share of the total population. With the demise of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and President Biden saying he'll appoint a Black woman to Breyer's seat, in just a few months there will be only one Jewish justice left: Elena Kagan. Though Breyer's retirement lacks political or jurisprudential interest, then, it symbolizes the eclipse of a center-left, meritocratic, largely Jewish milieu that seemed ascendant just a few years ago.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The change isn't just about the fact that Ginsburg, Breyer, and Kagan happened to share Ashkanazi Jewish ancestry. While Breyer's family was longer established in the United States, they shared other similarities. All were brought up in big cities, excelled at rigorous public high schools, and went on to attend Ivy League or Ivy-adjacent universities before pursuing their legal careers. More than an accident of biography, they followed a recognizable track that produced an extraordinary number of politicians, scholars, and cultural figures around the middle of 20th century. (And that's just Ginsburg's alma mater, James Madison High School in Brooklyn.)

That familiar path has been eroding for decades, though. In part, it's been a victim of its own success. Whatever their innate capacities, the descendants of extraordinarily successful people rarely display the same drive as their pioneering forebears.

It was probably inevitable, then, that the entry of so many Jews into the upper tiers of American life would produce a slackening of collective energy. Until a little more than 50 years ago, Jews still faced meaningful discrimination in college admissions, professional hiring, and social institutions (in addition to challenges that Ginsburg and her contemporaries faced due to their sex). Today, they've become the legacy candidates who benefit from extensive preferences.

The geographic and cultural profile of American Jewry has also changed. Most Jews still live in the same regions as their immigrant ancestors, yet the old urban neighborhoods are almost at the limits of living memory. Outside the growing Orthodox community, moreover, the influence of traditional religious practices has almost vanished. One needn't accept cliches about an innate predilection for scholarship to wonder whether early encounters with the rigor of Torah study had something to do with an earlier generation of Jews' success in the law and other learned professions. In that respect, Breyer's secular upbringing and identity contrast with Ginsburg and Kagan's closer relationships to Judaism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In addition to these generational trends, though, the type of liberalism associated with the ascent of American Jews has grown radically unfashionable. More a sensibility than a doctrine, it tended to combine respect for expert authority and a commitment to personal freedom with an optimistic understanding of America as an imperfect but constantly improving country. Despite her role as a icon of the left, for example, Ginsburg in 2016 chided refusal to salute the flag by Colin Kaerpernick and other athletes as "dumb and disrespectful."

But Ginsburg's apology a few days later reflects the changing political tides. In 2016, her brand of patriotism was already being replaced by an angrier moralism that treated ongoing racial oppression rather than upward mobility as the defining story of American history.

Although the "great awokening" has affected nearly major institutions, the change has been particularly stark in the selective educational institutions that Jewish liberals once regarded as the model of all that was best in America. In San Francisco, New York, and other cities, admissions policies at the demanding public schools that all three recent Jewish Supreme Court justices attended are subject to bitter debate.

As with Breyer's retirement, it's reasonable to wonder how much any of this matters for people who are not professionally or personally obsessed with the issue. And the answer may be similar — that is, not very much. As American Jews have melted into the upper middle class, our abilities, interests, stories, and perspectives have also become less special and interesting. It is probably coincidental but also notable that Breyer is not only the most secular justice on the Court, but also the most personally and rhetorically anodyne.

Contrary to accusations that Biden intends to elevate identity over qualifications in picking a replacement, moreover, it's unlikely that the next justice's resume will look very different from Breyer's. Current indications suggest Biden is looking for a nominee with a similar profile of elite law degree, Supreme Court or other major clerkship, and experience as a federal judge. Experts can argue about the relation between those credentials and juristic excellence. On paper, though, the cursus honorum hasn't changed much.

In a sense, then, Breyer's retirement is the perfect symbol of the declining prominence and distinctiveness of a certain kind of American Jew. His assimilation was so complete that we'll barely notice when he's gone. From one perspective, that's a success. But for the American Jewish culture that helped define the 20th century, it's another step toward the end of the line.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The Supreme Court revives a family's quest to recover looted Nazi art

The Supreme Court revives a family's quest to recover looted Nazi artUnder the Radar The painting in question is currently in a Spanish museum

-

Supreme Court to hear case of web designer opposed to same-sex wedding clients

Supreme Court to hear case of web designer opposed to same-sex wedding clientsSpeed Read

-

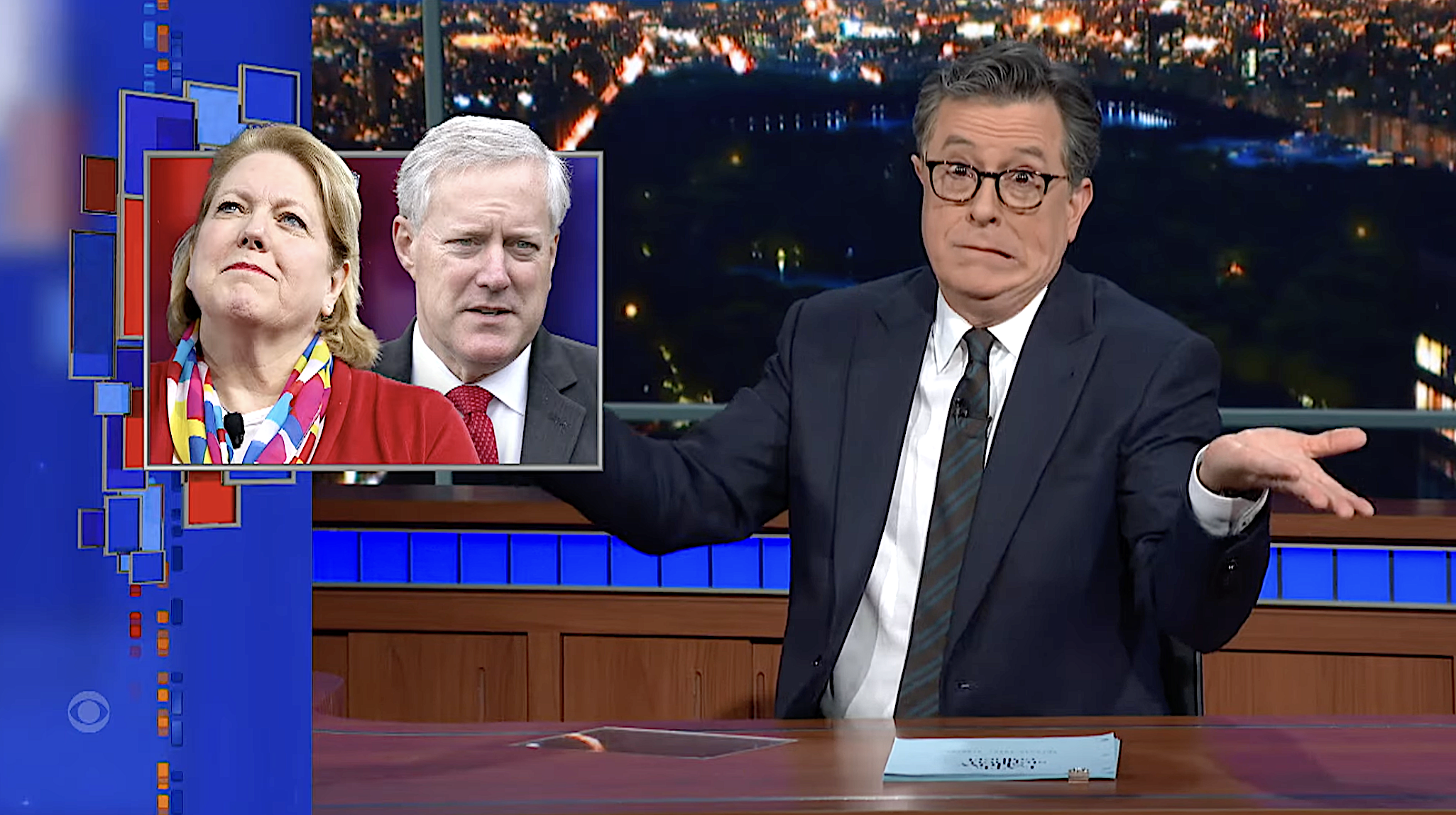

Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers, and Bill Maher explain why Ginni Thomas' texts are such 'a massive scandal'

Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers, and Bill Maher explain why Ginni Thomas' texts are such 'a massive scandal'Speed Read