The doctrine of stare decisis

The Supreme Court follows a tradition of honoring precedent — most of the time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Supreme Court follows a tradition of honoring precedent — most of the time. Here's everything you need to know:

What is stare decisis?

It's a centuries-old legal principle stating that judges should defer to past interpretations of statutes and the Constitution. It comes from the Latin expression stare decisis et non quieta movere, meaning, "to stand by things decided and not disturb the calm." Erring on the side of upholding precedent makes the law seem "evenhanded" and "predictable," then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote in 1984. Justice Louis Brandeis had gone further in 1932, writing, "In most matters it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than that it be settled right." But periodically throughout U.S. history — about 232 times, to be precise — justices have disregarded stare decisis and overruled their predecessors. A 5-4 conservative majority appears poised to do that with Roe v. Wade, and Justice Samuel Alito devotes a substantial chunk of his leaked draft opinion to arguing why Roe was "egregiously wrong from the start" and thus unworthy of stare decisis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When can precedent be overruled?

Whenever a majority of Supreme Court justices feel like it. Some legal scholars argue that a select group of old, landmark cases should be considered irreversible "super precedent," but the court has observed repeatedly that stare decisis is not an "inexorable command." In a 2020 opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh mapped a seven-prong test for applying stare decisis: the quality of the precedent's reasoning, the precedent's consistency with other decisions, changes in law since, changes in facts since, the decision's "workability," the degree to which people have come to rely on it, and the precedent's age. Nearly everyone agrees, at least in theory, that it's not sufficient for new justices to personally disagree with earlier rulings on ideological grounds. In 2018, when five conservatives ruled that the First Amendment protects public-sector employees from being forced to pay union dues if they're not members, Justice Elena Kagan accused the majority of overturning a 1977 precedent "for no exceptional or special reason, but because it never liked the decision."

What's been overturned?

Some of the Supreme Court's most momentous decisions rejected precedent. Perhaps most famously, in 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ended racial segregation in public schools, overturning the "separate but equal" doctrine established in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. In 1976, the court ruled that Georgia's administration of the death penalty didn't violate the Eighth Amendment's prohibitions against cruel and unusual punishment, invalidating a decision from just five years earlier. More recently, the court in 2003 deemed laws banning sodomy and gay sex to be unconstitutional, reversing a 1986 decision, and in 2015 identified a right to same-sex marriage, overturning a one-sentence ruling from 1972. The 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC, striking down limits on corporate campaign spending, overturned two decisions, one as recent as 2003. When the court upheld President Trump's travel ban, in 2018, Chief Justice John Roberts went out of his way to disown the infamous 1944 decision in Korematsu v. United States, which let stand the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. "Korematsu was gravely wrong," Roberts wrote, and "has no place in law under the Constitution."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is there an ideological pattern?

Legal scholars like to joke that stare decisis is Latin for "stand by things decided when it suits our purposes." Every justice claims to respect stare decisis, but both liberals and conservatives have attacked their rivals for abandoning precedent when ideologically convenient. The ultra-liberal Warren court overturned up to four precedents per term. Roberts frequently expounds on the importance of stare decisis, but since 2005 he has voted with the majority about three-quarters of the time on rulings that overturned precedent. Conservative Justice Clarence Thomas is leading the charge to discount stare decisis, saying the court should not be bound by "demonstrably incorrect'' previous rulings. "We use stare decisis as a mantra when we don't want to think," he said.

Are more precedents in jeopardy?

Liberal court-watchers say Alito's leaked opinion is a blueprint for gutting other privacy-related rights. In his draft, Alito says Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 case affirming the central holding of Roe, must be overturned because there is no right to privacy or abortion in the Constitution, and that implicit rights must be "deeply rooted in this Nation's history.'' But previous courts cited a right to privacy as the constitutional basis for protecting access to contraception, legalizing gay sex and same-sex marriage, and other rights that are now in the conservative movement's crosshairs. Alito insists that overturning Roe does not threaten "precedents that do not concern abortion," but his assurance is hardly binding. Two years ago, he and Thomas complained in an opinion that the court had created "a novel constitutional right" in same-sex marriage that was "ruinous" to "religious liberty." The court, they said, "has created a problem that only it can fix."

Misleading the Senate?

Trump's high-court nominees — Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett — reportedly all plan to join Alito and Thomas in overturning Roe. The news drew outrage from senators such as Republican Susan Collins of Maine, who said their vote would be "completely inconsistent" with what Gorsuch and Kavanaugh in particular said during their confirmation hearings. Conservatives, however, say the future justices chose their words carefully. Gorsuch told the Senate that Roe "has been reaffirmed," adding, "a good judge" will treat it "like any other" precedent. "I accept the law of the land," he testified. Kavanaugh called the case "important precedent of the Supreme Court that has been reaffirmed many times." Barrett, whose personal opposition as a Catholic to abortion drew intense scrutiny during her confirmation, declined to call the right to an abortion a "super precedent," saying, "I'm answering a lot of questions about Roe, which I think indicates that Roe doesn't fall into that category." After Alito's draft leaked, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said, "Justices looking at you in the face and telling you one thing and then doing something different — that's very troubling."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

How far does religious freedom go in prison? The Supreme Court will decide.

How far does religious freedom go in prison? The Supreme Court will decide.The Explainer The plaintiff was allegedly forced to cut his hair, which he kept long for religious reasons

-

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBI

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBIThe Explainer The case arose after the FBI admitted to raiding the wrong house in 2017

-

Supreme Court to weigh transgender care limits

Supreme Court to weigh transgender care limitsSpeed Read The case challenges a Tennessee law restricting care for trans minors

-

Supreme Court wary of state social media regulations

Supreme Court wary of state social media regulationsSpeed Read A majority of justices appeared skeptical that Texas and Florida were lawfully protecting the free speech rights of users

-

The pros and cons of a written constitution

The pros and cons of a written constitutionPros and Cons Clarity no substitute for flexibility, say defenders of Britain's unwritten rulebook

-

Judges allowed to use ChatGPT to write legal rulings

Judges allowed to use ChatGPT to write legal rulingsSpeed Read New guidance says AI useful for summarising text but must not be used to conduct research or legal analysis

-

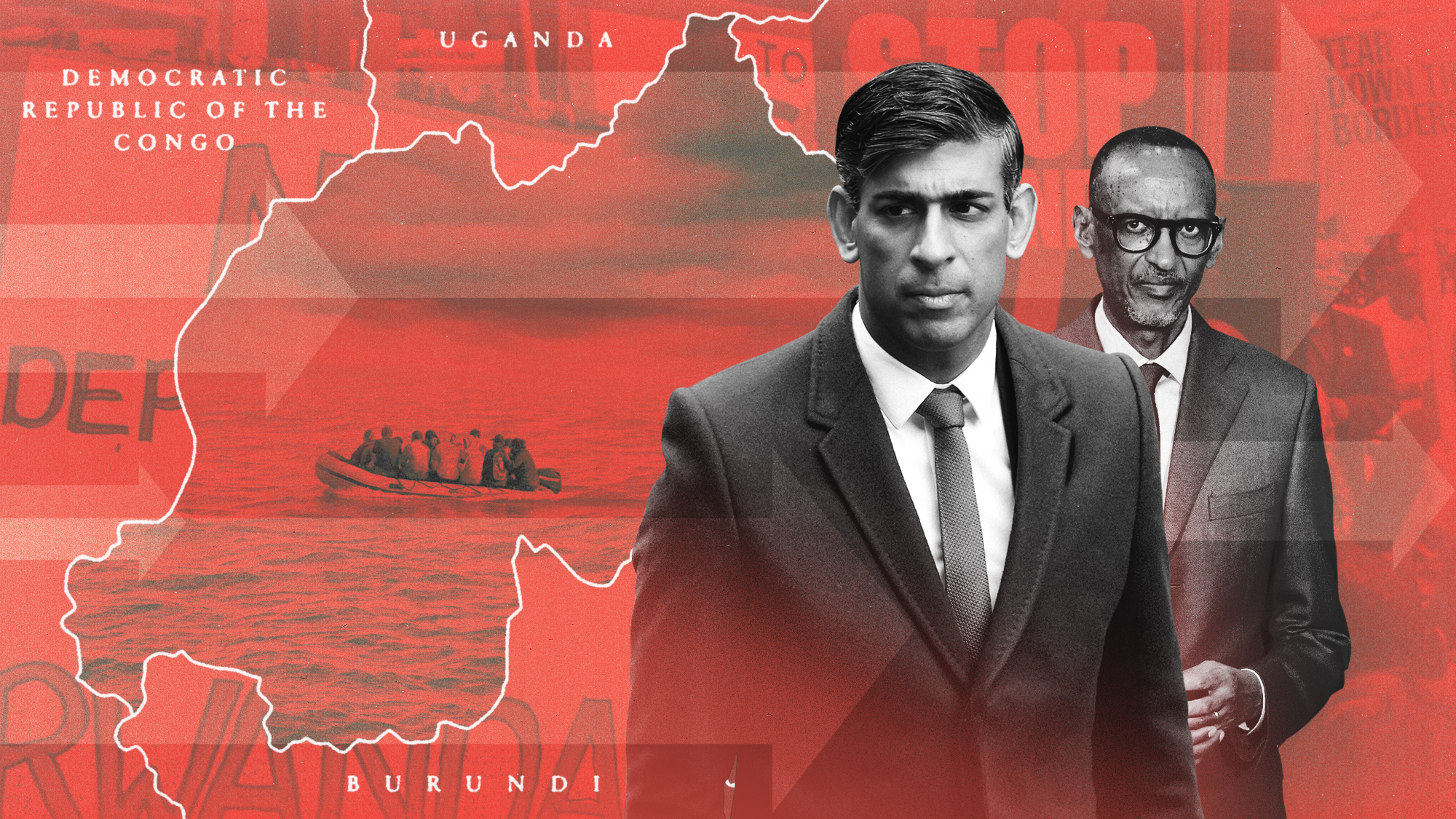

Pros and cons of the Rwanda deportation policy

Pros and cons of the Rwanda deportation policyPros and Cons Supporters claim it acts as a deterrent but others say it is illegal and not value for money

-

Is the Comstock Act back from the dead?

Is the Comstock Act back from the dead?Speed Read How a 19th-century law may end access to the abortion pill