Keir Starmer: preparing to be prime minister?

Pundits say Labour leader’s shake-up of top team shows the party is gearing up ‘for power’

Keir Starmer is putting Labour on an “election footing” with critical changes to his top team after telling party staff that the “government’s collapse has given us a huge chance”.

The Labour leader reportedly said that “this is not time for complacency or caution” as he announced the sacking of his chief-of-staff Sam White. A spokesperson added that the “long-planned” structural changes had been “brought forward in light of the Conservative Party implosion”.

White has been blamed for several “strategic missteps that enraged the shadow cabinet”, said The Times. Critics within the party “said his style was defined by an excess of caution that too often prevented Starmer from seizing the initiative”, according to the paper.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Starmer now appears primed for a fresh push to win power after telling staff this week that a general election could happen “at any time”.

What is Keir Starmer’s background?

Starmer is “not just another London elite”, said Politico in 2020, after he succeeded Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader.

The now party chief was born in the London borough of Southwark on 2 September 1962, but he and his three siblings grew up in Oxted, Surrey. As the politician has repeatedly pointed out, his father, Rod Starmer, was a toolmaker, and his mother, Josephine Baker, was a nurse.

Starmer told BBC Radio 5 Live last month that he didn’t grow up in “great poverty”, but “said he could relate to those currently facing difficulties as the cost-of-living crisis hits households”, Sky News reported.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“I actually know what it is like to sit around the kitchen table not being able to pay your bills,” Starmer said.

When he was 11, his mother was diagnosed with Still’s disease, a rare and incurable form of inflammatory arthritis that meant she “could barely walk for most of her life”, Starmer told Politico’s London Playbook in 2019.

The impact of her illness was “really difficult” but “formative”, he said, adding that his mother would “never ever, ever go to private health”. She died two weeks before Starmer was first elected as a member of Parliament, for Holborn and St Pancras in north London in 2015.

As a schoolboy, Starmer attended Redhill Grammar, where fellow pupils included Fat Boy Slim. Starmer told Channel 4 News’s Cathy Newman earlier this year that he “did violin lessons” with the now music star, real name Norman Cook, “back in the day”.

Starmer also became a member of East Surrey Young Socialists as a teenager, before going on to study law at the University of Leeds followed by a Master’s at Oxford.

Appearing on Piers Morgan’s ITV show Life Stories last year, he recalled: “I spent my university days in the library, studying”. When Morgan launched into what The Tab described as “an interrogation” about whether he took drugs as a student, Starmer denied the suggestion, but added: “We worked hard and played hard.”

He has been married to Victoria Alexander, a former solicitor-turned-NHS occupational health worker, since 2007, and the couple have two children.

What did Starmer do before entering politics?

Starmer had a long career as a lawyer before first being elected as an MP in May 2015, at the age of 52.

He started out as a defence barrister focusing on human rights, and won a number of high-profile cases including overturning death row sentences and assisting in the years-long “McLibel” case. His first mention in The Lawyer was in 1995, and he went on to get “regular name-checks” in lists of “ones to watch”, said the industry magazine.

Starmer became Queen’s Counsel in 2002, before being appointed director of public prosecutions and head of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) six years later.

He received a knighthood in 2014 for his services to criminal justice, and “‘invited his parents to Buckingham Palace for the event, who in turn brought along the family dog”, said Labour.org.uk.

At the CPS, he “is remembered for his focus on standards and best practices”, biographer Oliver Eagleton told The Guardian’s First Edition newsletter editor Archie Bland earlier this year. And his credentials as a former director of public prosecutions put Starmer “a cut above the rest of Labour’s frontbench in the eyes of many Conservatives”, said Politico.

After becoming an MP, Starmer served as shadow minister for immigration. In 2016, he was appointed shadow Brexit secretary under Corbyn, sitting “at the heart of Labour’s frontbench during the tumultuous years of the UK’s exit from the European Union”, said Politics.co.uk. Starmer was “the key figure in steering” Labour to back a second referendum in the 2019 election, said Politico, but has “had to make peace” with Brexit.

In 2020, Starmer beat Rebecca Long-Bailey and Lisa Nandy to succeed Coryn as party leader, securing 56.2% of the vote. “But the next contest will be the harder one,” said Politico said, which pointed out that following Labour’s losses in the 2019 general election, the party needed to “overturn a Conservative majority of 80 seats” to claim power.

Starmer acknowledged that the party had a “mountain to climb”. But a series of scandals during Boris Johnson’s tenure, and the recent economic crises triggered by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini budget, appear to have put a Labour victory within reach as the “political pendulum swings”, said The Observer.

Is he popular enough to become PM?

Starmer was “widely written off” as “a grey man in a blue suit” for the first two years of his party leadership, said the Financial Times. He has repeatedly been accused of lacking charisma, with even members of his own party describing him as boring – reportedly prompting Starmer to tell his shadow cabinet that “what’s boring is being in opposition”.

But public opinion began to shift earlier this year, as the Conservatives faced “a seemingly endless succession of revelations about sleaze and scandal”, the newspaper said.

A poll of 1,712 British adults last month by YouGov and The Times found that 54% would vote for Labour, while 21% would back the Tories. And 44% thought Starmer would make the best prime minister, compared with Truss’s 15%.

In a separate Ipsos survey of 1,000 people, 51% thought Starmer was likely to become PM, up 23% from January.

The mood was jubilant at Labour’s party conference last month, with the Tories “close to losing the plot” just weeks into Truss’s premiership, said Andrew Marr in The New Statesman. Starmer delivered a keynote speech that “showed he is a prime minister in waiting”, portraying Labour “as a party of reassurance, serious-minded common sense and patient duty”, Marr wrote.

The subsequent shake-up of Starmer’s top team shows the Labour leader is “preparing for power”, said Politico’s London Playbook.

As well as the sacking of White, a former senior special adviser during the premierships of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, Labour’s policy and communications teams are set to move from Starmer’s office to party headquarters.

Labour sources told The Guardian’s Jess Elgot that White, who had been Starmer’s chief of staff for a year, was not expected to be replaced immediately and that “the priority for the new role would be leading on transition to government work as well as day-to-day management”.

The shake-up was announced hours after former shadow minister Sam Tarry was deselected as Labour’s candidate for Ilford South, with local party members voting by 499 to 361 for council leader Jas Athwal to be their representative. The Times said the decision “will have been quietly welcomed by the Labour leadership”, who ousted Tarry earlier this summer after he conducted unapproved media interviews.

Julia O'Driscoll is the engagement editor. She covers UK and world news, as well as writing lifestyle and travel features. She regularly appears on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast, and hosted The Week's short-form documentary podcast, “The Overview”. Julia was previously the content and social media editor at sustainability consultancy Eco-Age, where she interviewed prominent voices in sustainable fashion and climate movements. She has a master's in liberal arts from Bristol University, and spent a year studying at Charles University in Prague.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

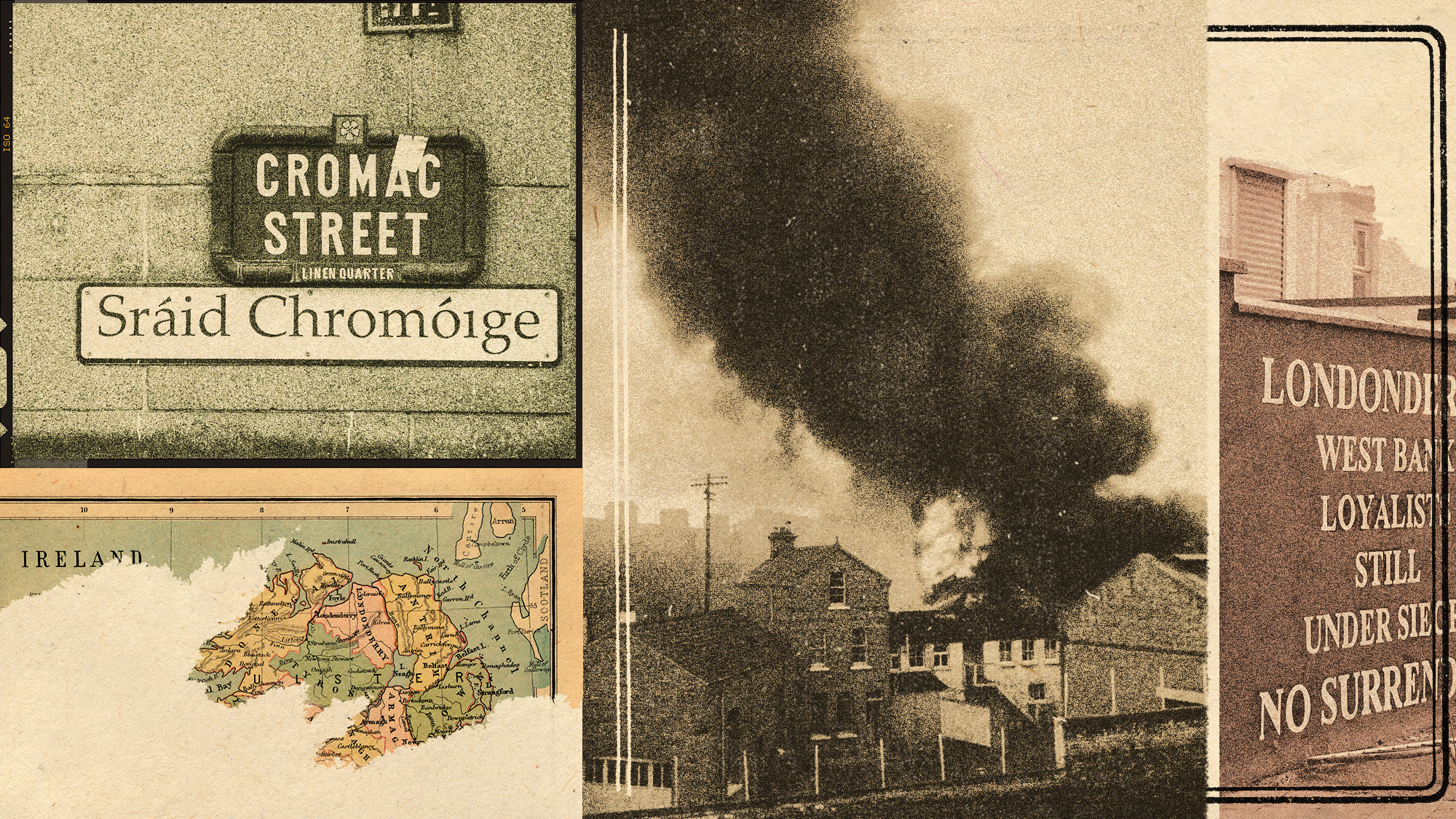

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?Today's Big Question Pathway to a coup ‘still unclear’ even as potential challengers begin manoeuvring into position

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies

-

Three consequences from the Jenrick defection

Three consequences from the Jenrick defectionThe Explainer Both Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage may claim victory, but Jenrick’s move has ‘all-but ended the chances of any deal to unite the British right’

-

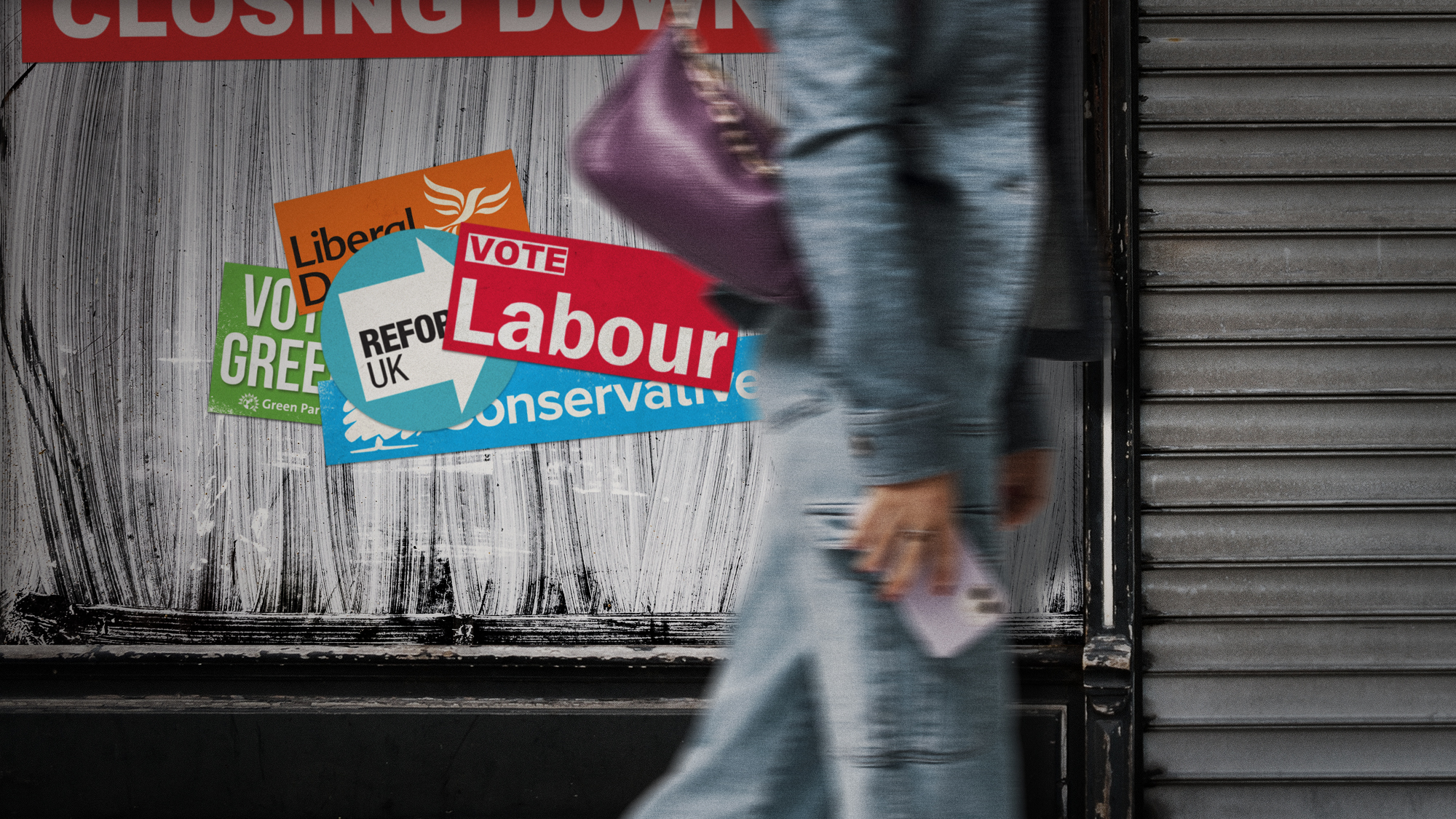

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?Today's Big Question Resurfaced social media posts appear to show the democracy activist calling for the killing of Zionists and police